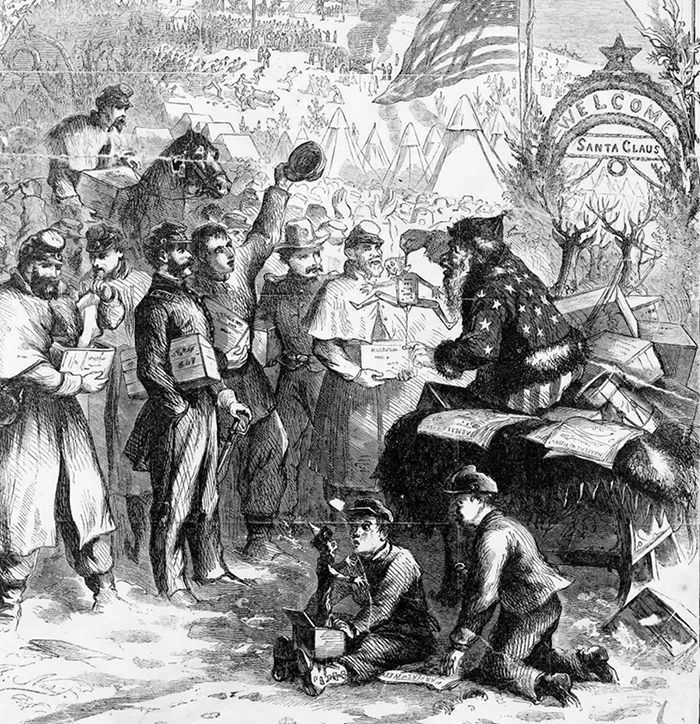

It will no doubt come as a relief to many readers that Santa Claus appears to have been a Union supporter. We know this because he appears distributing gifts to soldiers from that side of the Mason-Dixon in one of his earliest depictions. That illustration, “Santa Claus in Camp” (above), first appeared in the Harper’s Weekly Christmas issue of 1862, when the American Civil War was still tearing its way through the country. Its artist, a Bavarian immigrant named Thomas Nast, is now remembered for having first drawn the Democratic Party as a donkey and the Republican Party as an elephant, but he also did more than anyone else to create the image of Santa Claus recognized around the world today: more than Norman Rockwell, and more, even, than the Coca-Cola Company.

Santa Claus is an Anglicization of Sinterklaas, a Dutch name for Saint Nicholas, who lived and died in what’s now Turkey in the third and fourth centuries, and who’s been remembered since for his kindness to children. Few of us would recognize him in his portrait from 1294 that is included in the Public Domain Review’s pictorial history of Santa Claus, but with the passing of the centuries, his images became mixed with those of other flying, winter-associated characters from Germanic and Norse myth. In 1822, Clement Moore performed a defining act of rhyming synthesis with his poem “A Visit from St. Nicholas” (often called “ ‘Twas the Night Before Christmas”): in its verses we find the bundle of toys, the rosy cheeks, the white beard, the belly shaking like a bowl full of jelly.

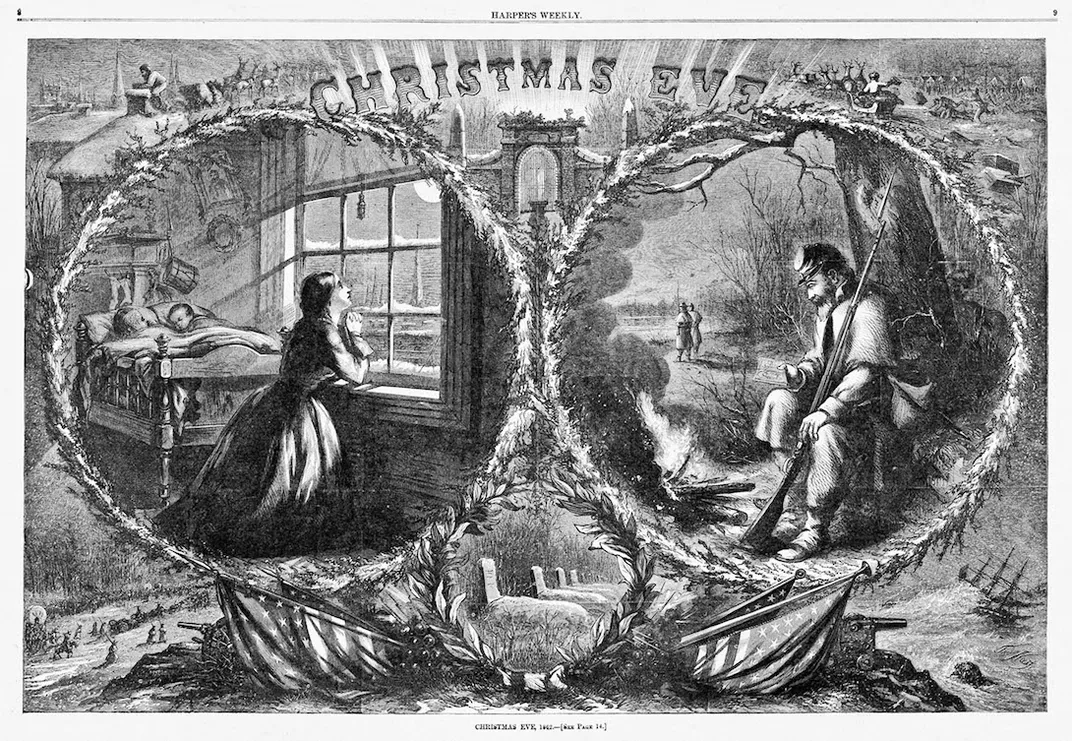

Nast clearly understood not just the appeal of Moore’s description, but also the character’s propaganda value. His very first renditions of Santa Claus appear in the upper corners of an 1862 Harper’s Weekly illustration of a praying wife and her Yankee soldier husband. Nearly two decades later, Nast drew the cartoon “Merry Old Santa Claus” (immediately above), whose central figure remains immediately recognizable to us today, even as its motivating political cause of higher wages for the military has become obscure. In the twentieth century, the iconic Father Christmas would be enlisted again to lend public support to U.S. efforts in World War I and II, in the very decades when Rockwell was further refining and cementing his image in popular culture. The once-unlikely result was an American Santa Claus: “the symbol of our empire,” in the words of The New Yorker’s Adam Gopnik, “as much as Apollo was of the Hellenic one.”

Related Content:

Watch Santa Claus, the Earliest Movie About Santa in Existence (1898)

Hear “Twas The Night Before Christmas” Read by Stephen Fry & John Cleese

Bob Dylan Reads “ ‘Twas the Night Before Christmas” On His Holiday Radio Show (2006)

Slavoj Žižek Answers the Question “Should We Teach Children to Believe in Santa Claus?”

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities and the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles. Follow him on the social network formerly known as Twitter at @colinmarshall.

Leave a Reply