The end of the nineteenth century is still widely referred to as the fin de siècle, a French term that evokes great, looming cultural, social, and technological changes. According to at least one French mind active at the time, among those changes would be a fin des livres as humanity then knew them. “I do not believe (and the progress of electricity and modern mechanism forbids me to believe) that Gutenberg’s invention can do otherwise than sooner or later fall into desuetude,” says the character at the center of the 1894 story “The End of Books.” “Printing, which since 1436 has reigned despotically over the mind of man, is, in my opinion, threatened with death by the various devices for registering sound which have lately been invented, and which little by little will go on to perfection.”

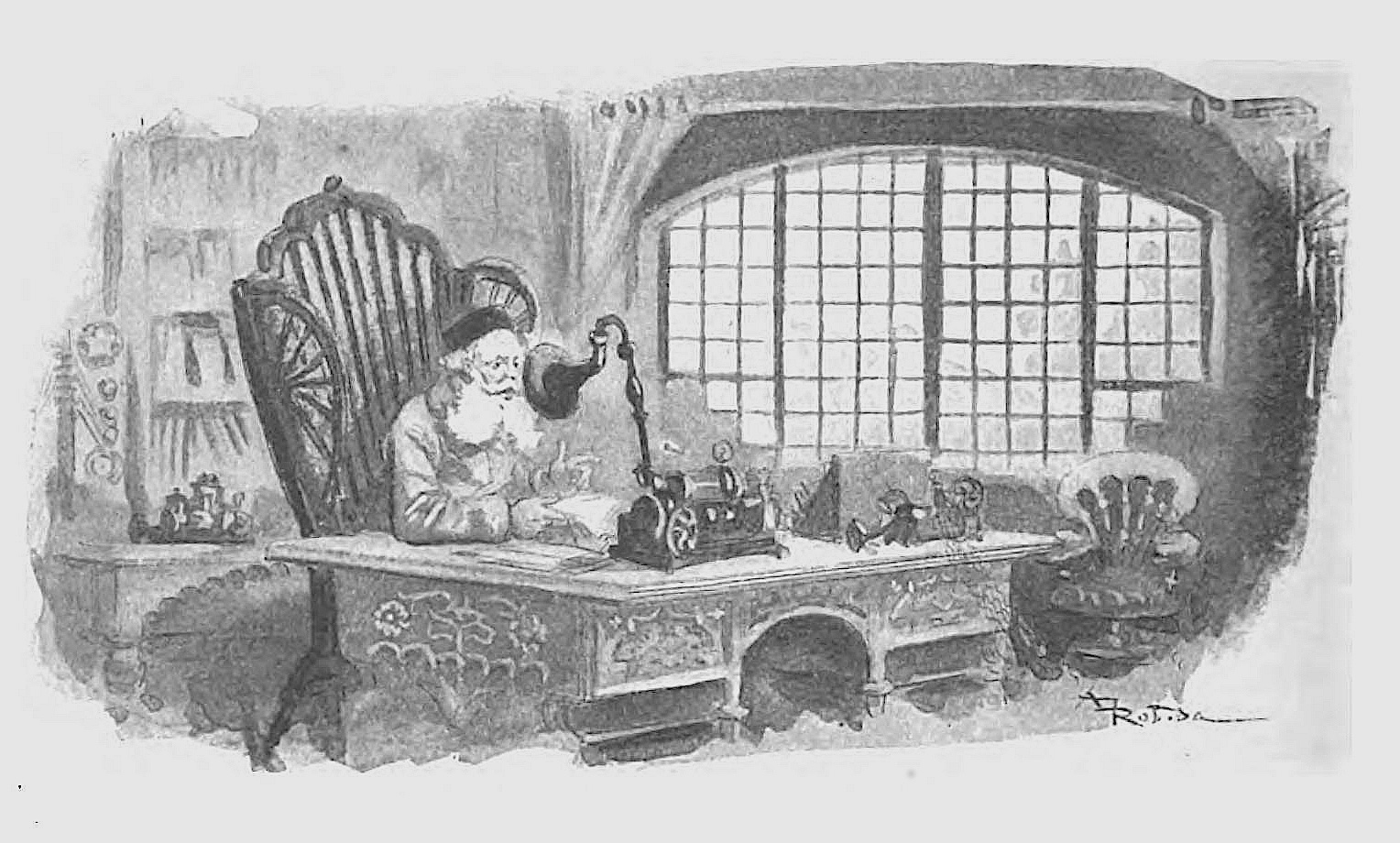

First published in an issue of Scribner’s Magazine (viewable at the Internet Archive or this web page), “The End of Books” relates a conversation among a group of men belonging to various disciplines, all of them fired up to speculate on the future after hearing it proclaimed at London’s Royal Institute that the end of the world was “mathematically certain to occur in precisely ten million years.” The participant foretelling the end of books is, somewhat ironically, called the Bibliophile; but then, the story’s author Octave Uzanne was famous for just such enthusiasms himself. Believing that “the success of everything which will favor and encourage the indolence and selfishness of men,” the Bibliophile asserts that sound recording will put an end to print just as “the elevator has done away with the toilsome climbing of stairs.”

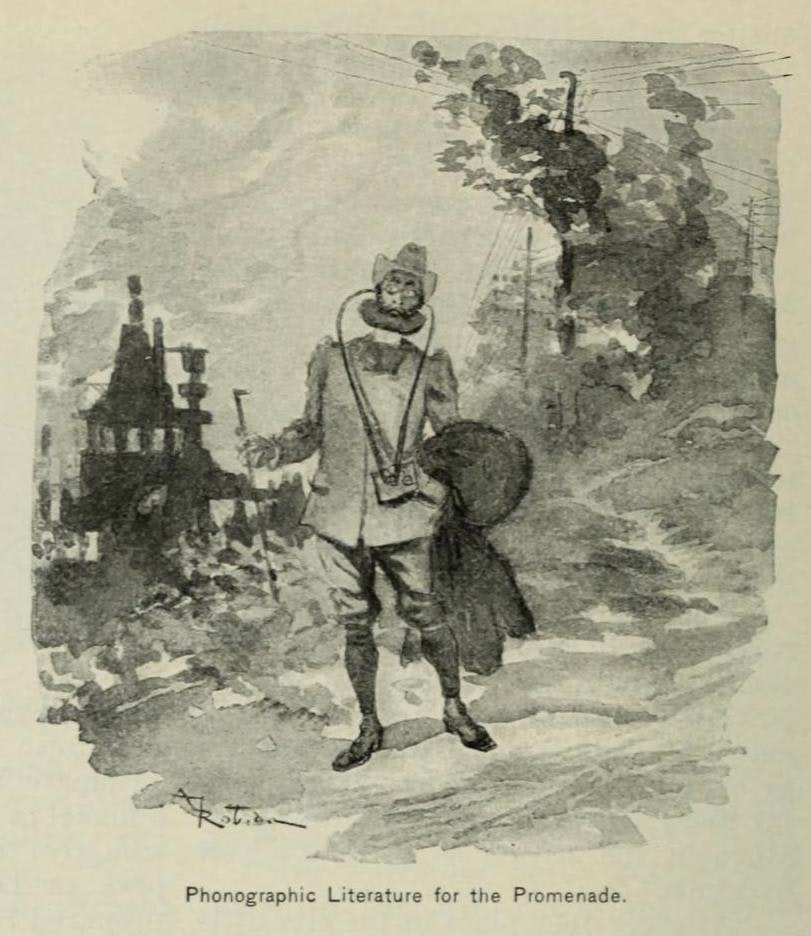

These 130 or so years later, anyone who’s been to Paris knows that the elevator has yet to finish that job, but much of what the Bibliophile predicts has indeed come true in the form of audiobooks. “Certain Narrators will be sought out for their fine address, their contagious sympathy, their thrilling warmth, and the perfect accuracy, the fine punctuation of their voice,” he says. “Authors who are not sensitive to vocal harmonies, or who lack the flexibility of voice necessary to a fine utterance, will avail themselves of the services of hired actors or singers to warehouse their work in the accommodating cylinder.” We may no longer use cylinders, but Uzanne’s description of a “pocket apparatus” that can be “kept in a simple opera-glass case” will surely remind us of the Walkman, the iPod, or any other portable audio device we’ve used.

All this should also bring to mind another twenty-first century phenomenon: podcasts. “At home, walking, sightseeing,” says the Bibliophile, “fortunate hearers will experience the ineffable delight of reconciling hygiene with instruction; of nourishing their minds while exercising their muscles.” This will also transform journalism, for “in all newspaper offices there will be Speaking Halls where the editors will record in a clear voice the news received by telephonic despatch.” But how to satisfy man’s addiction to the image, well in evidence even then? “Upon large white screens in our own homes,” a “kinetograph” (which we today would call a television) will project scenes fictional and factual involving “famous men, criminals, beautiful women. It will not be art, it is true, but at least it will be life.” Yet however striking his prescience in other respects, the Bibliophile didn’t know – though Uzanne may have — that books would persist through it all.

Related content:

1,000 Free Audio Books: Download Great Books for Free

How the Year 2440 Was Imagined in a 1771 French Sci-Fi Novel

A 1947 French Film Accurately Predicted Our 21st-Century Addiction to Smartphones

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities and the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles. Follow him on the social network formerly known as Twitter at @colinmarshall.

The original text, in the original French, and with all the illustrations, was posted in 2005 on the Hidden Knowledge website.

I attempted to post the link, but the robot at PW decided it was spam.

Kindly enjoy!

Michael Ward

Publisher, Hidden Knowledge

Search for the title “La Fin des Livres”.

Sorry, the overactive robot is at Open Culture. ‑MW