Walter Keane—supposed painter of “Big Eyed Children” and subject of a 2014 Tim Burton film—made a killing, attaining almost Thomas Kinkade-like status in the middlebrow art market of the 1950s and 60s. As it turns out, his wife, Margaret was in fact the artist, “painting 16 hours a day,” according to a Guardian profile. In some part, the story may illustrate how easy it was for a man like Walter to get millions of people to see what they wanted to see in the picture of success—a charismatic, talented man in front, his quiet, dutiful wife behind. Burton may not have taken too much license with the commonplace attitudes of the day when he has Christoph Waltz’s Walter Keane tell Margaret, “Sadly, people don’t buy lady art.”

And yet, far from the Keanes’ San Francisco, and perhaps as far as a person can get from Margaret’s frustrated acquiescence, we have Frida Kahlo creating a body of work that would eventually overshadow her husband’s, muralist Diego Rivera. Unlike Walter Keane, Rivera was a very good painter who did not attempt to overshadow his wife. Instead of professional jealousy, he had plenty of the personal variety. Even so, Rivera encouraged Kahlo’s career and recognized her formidable talent, and she, in turn, supported him. In 1933, when Florence Davies—whom Kahlo biographer Gerry Souter describes as “a local news hen”—caught up with her in Detroit, Kahlo “played the cheeky, but adoring wife” of Diego while he labored to finish his famous Detroit mural project.

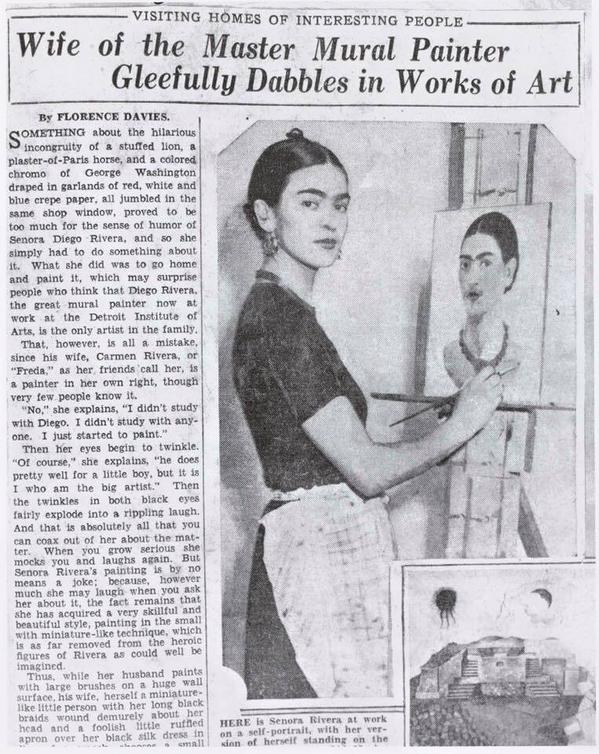

That may be so, but she did not do so at her own expense. Quite the contrary. Asked if Diego taught her to paint, she replies, “’No, I didn’t study with Diego. I didn’t study with anyone. I just started to paint.’” At which point, writes Davies, “her eyes begin to twinkle” as she goes on to say, “’Of course, he does pretty well for a little boy, but it is I who am the big artist.’” Davies praises Kahlo’s style as “skillful and beautiful” and the artist herself as “a miniature-like little person with her long black braids wound demurely about her head and a foolish little ruffled apron over her black silk dress.” And yet, despite Kahlo’s confidence and serious intent, represented by a prominent photo of her at serious work, Davies—or more likely her editor—decided to title the article, “Wife of the Master Mural Painter Gleefully Dabbles in Works of Art,” a move that reminds me of Walter Keane’s patronizing attitude.

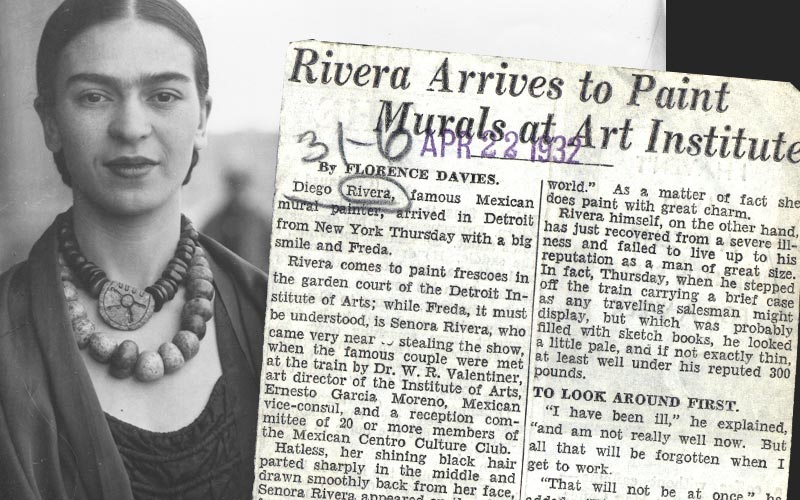

The belittling headline is quaint and disheartening, speaking to us, like the unearthed 1938 letter from Disney to an aspiring female animator, of the cruelty of casual sexism. Davies apparently filed another article on Rivera the year prior. This time the headline doesn’t mention Frida, though her fierce unflinching gaze, not Rivera’s wrestler’s mug, again adorns the spread. One sentence in the article says it all: “Freda [sic], it must be understood, is Senora Rivera, who came very near to stealing the show.” Davies then goes on to again describe Kahlo’s appearance, noting of her work only that “she does paint with great charm.” Six years later, Kahlo would indeed steal the show at her first and only solo show in the United States, then again in Paris, where surrealist maestro Andre Breton championed her work and the Louvre bought a painting, its first by a twentieth-century Mexican artist.

And Margaret Keane? She eventually sued Walter and now reaps her own rewards. You can buy one of her paintings here.

Note: An earlier version of this post appeared on our site in 2015.

Related Content:

Photos of a Very Young Frida Kahlo, Taken by Her Dad

A Brief Animated Introduction to the Life and Work of Frida Kahlo

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

Leave a Reply