I mean, the idea that you would give a psychedelic—in this case, magic mushrooms or the chemical called psilocybin that’s derived from magic mushrooms—to people dying of cancer, people with terminal diagnoses, to help them deal with their — what’s called existential distress. And this seemed like such a crazy idea that I began looking into it. Why should a drug from a mushroom help people deal with their mortality?

–Michael Pollan in an interview with Terry Gross, “‘Reluctant Psychonaut’ Michael Pollan Embraces ‘New Science’ Of Psychedelics”

Around the same time Albert Hofmann synthesized LSD in the early 1940s, a pioneering ethnobotanist, writer, and photographer named Richard Evan Schultes set out “on a mission to study how indigenous peoples” in the Amazon rainforest “used plants for medicinal, ritual and practical purposes,” as an extensive history of Schultes’ travels notes. “He went on to spend over a decade immersed in near-continuous fieldwork, collecting more than 24,000 species of plants including some 300 species new to science.”

Described by Jonathan Kandell as “swashbuckling” in a 2001 New York Times obituary, Schultes was “the last of the great plant explorers in the Victorian tradition.” Or so his student Wade Davis called him in his 1995 bestseller The Serpent and the Rainbow. He was also “a pioneering conservationist,” writes Kandell, “who raised alarms in the 1960’s—long before environmentalism became a worldwide concern.” Schultes defied the stereotype of the colonial adventurer, once saying, “I do not believe in hostile Indians. All that is required to bring out their gentlemanliness is reciprocal gentlemanliness.”

Schultes returned to teach at Harvard, where he reminded his students “that more than 90 tribes had become extinct in Brazil alone over the first three-quarters of the 20th century.” While his research would have significant influence on figures like Aldous Huxley, William Burroughs, and Carlos Castaneda, “writers who considered hallucinogens as the gateways to self-discovery,” Schultes was dismissive of the counterculture and “disdained these self-appointed prophets of an inner reality.”

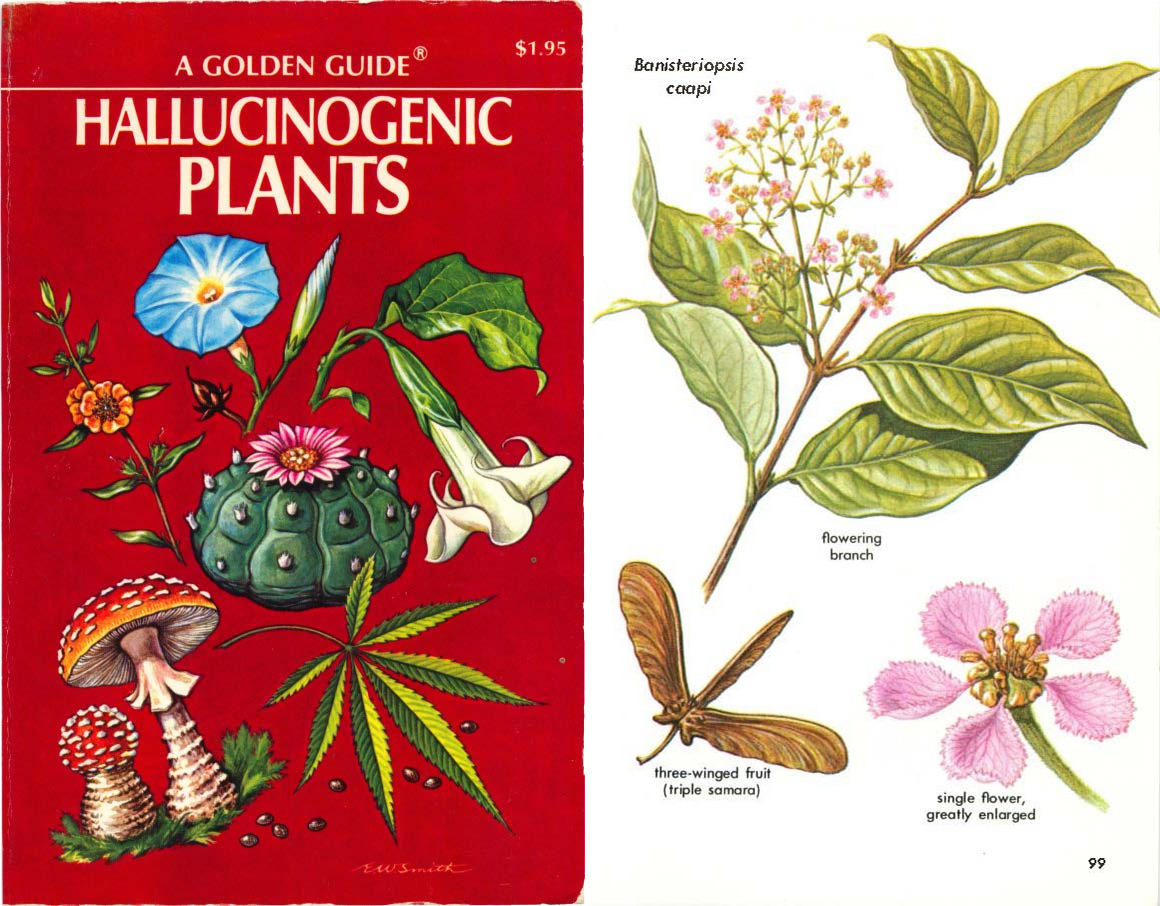

Rather than promoting recreational use, Schultes became known as “the father of a new branch of science called ‘ethnobotany,’ the field that explores the relationship between indigenous people and their use of plants,” writes Luis Sequeira in a biographical note. One of Schultes’ publications, the Golden Guide to Hallucinogenic Plants, has sadly fallen out of print, but you can find it online, in full, at the Vaults of Erowid. Pricey out-of-print copies can still be purchased.

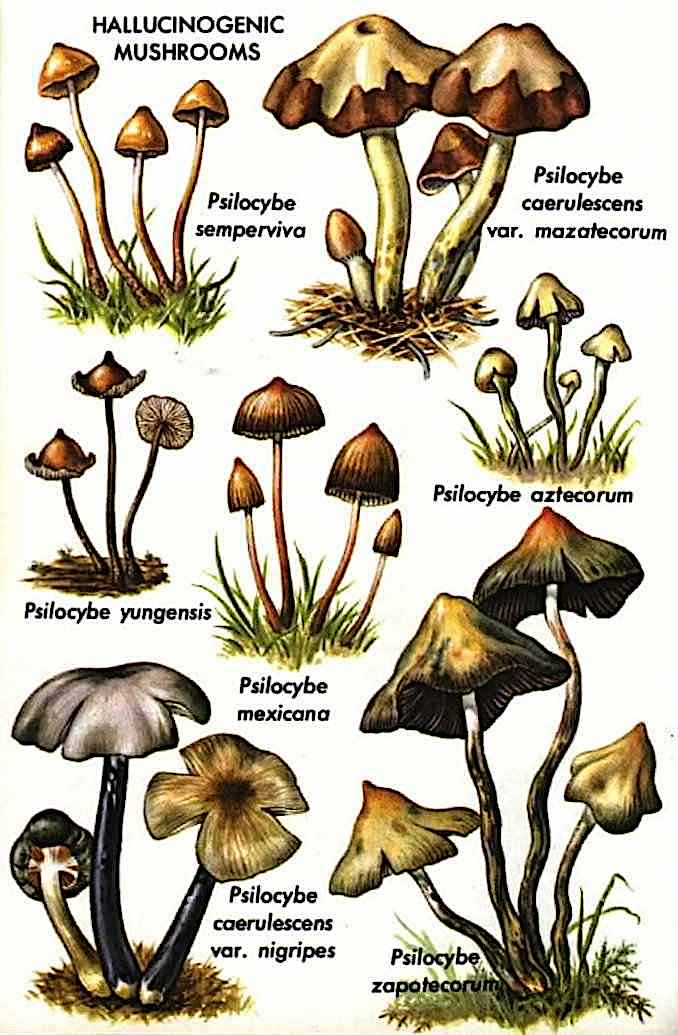

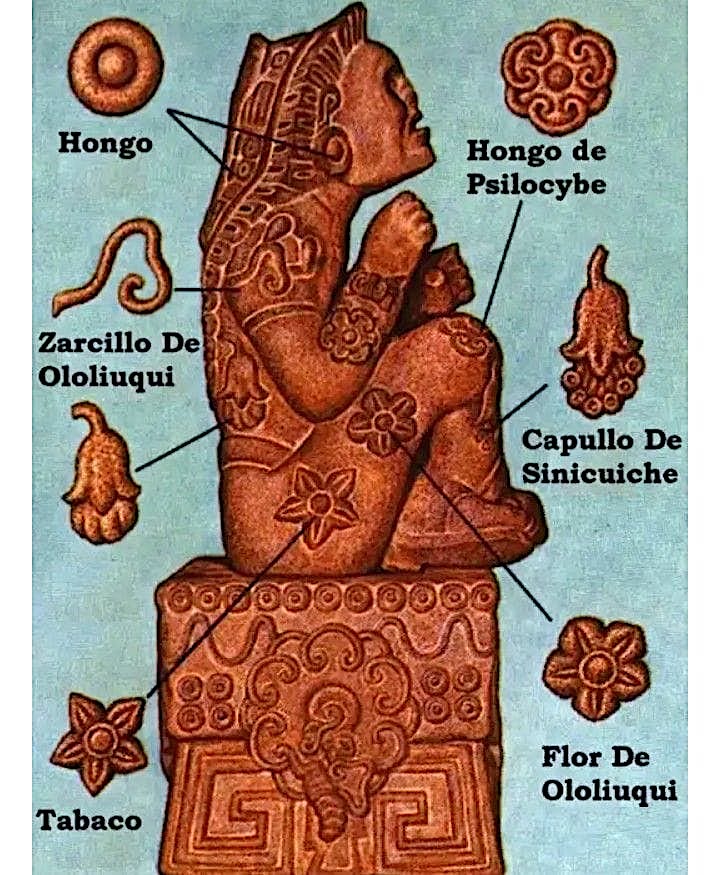

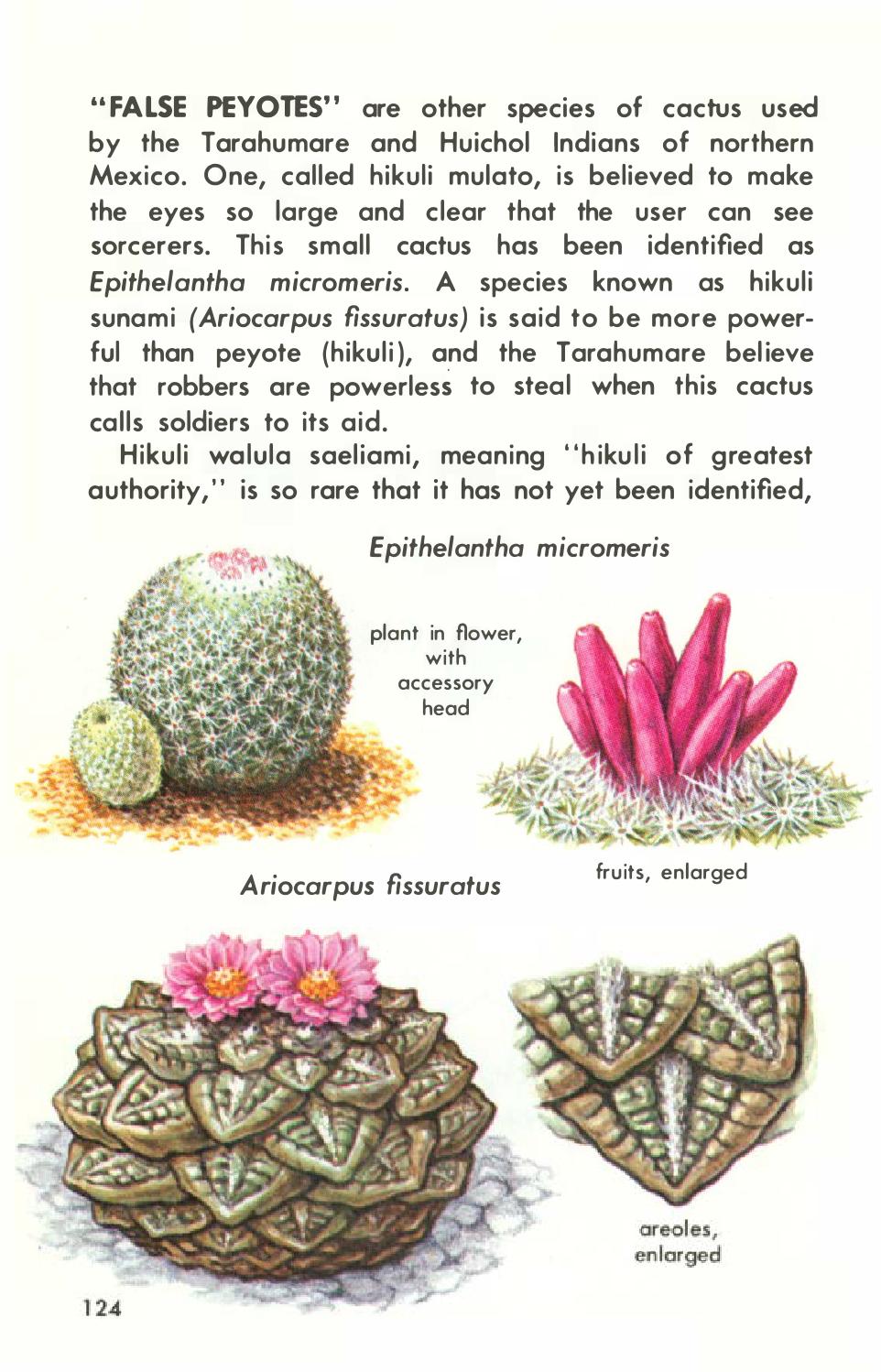

Described on Amazon as “a nontechnical examination of the physiological effects and cultural significance of hallucinogenic plants used in ancient and modern societies,” the book covers peyote, ayahuasca, cannabis, various psychoactive mushrooms and other fungi, and much more. In his introduction, Schultes is careful to separate his research from its appropriation, dismissing the term “psychedelic” as etymologically incorrect and “biologically unsound.” Furthermore, he writes, it “has acquired popular meanings beyond the drugs or their effects.”

Schultes’ interests are scientific—and anthropological. “In the history of mankind,” he writes, “hallucinogens have probably been the most important of all the narcotics. Their fantastic effects made them sacred to primitive man and may even have been responsible for suggesting to him the idea of deity.” He does not exaggerate. Schultes’ research into the religious and medicinal uses of natural hallucinogens led him to dub them “plants of the gods” in a book he wrote with Albert Hofmann, discoverer of LSD.

Neither scientist sought to start a psychedelic revolution, but it happened nonetheless. Now, another revolution is underway—one that is finally revisiting the science of ethnobotany and taking seriously the healing powers of hallucinogenic plants. It is hardly a new science among scholars in the West, but the renewed legitimacy of research into hallucinogens has given Schultes’ research new authority. Learn from him in his Golden Guide to Hallucinogenic Plants online here.

Related Content:

The Romans Stashed Hallucinogenic Seeds in a Vial Made From an Animal Bone

Algerian Cave Paintings Suggest Humans Did Magic Mushrooms 9,000 Years Ago

A Bicycle Trip: Watch an Animation of The World’s First LSD Trip in 1943

Hofmann’s Potion: 2002 Documentary Revisits the History of LSD

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

Leave a Reply