If you’ve read one work of Hannah Arendt’s, it’s probably Eichmann in Jerusalem, her account of the trial of the eponymous Nazi official — and the source of her much-quoted phrase “the banality of evil.” That book came out in 1963, at which time Arendt still had a dozen productive years left. In fact, at the time of her sudden death in 1975, she had in her typewriter the first page of what would have been the third volume of her final work, The Life of the Mind. In its two completed volumes, she investigates the nature of thought and action, a preoccupation with the relationship between thinking and morality having been fired up within her at the Eichmann trial.

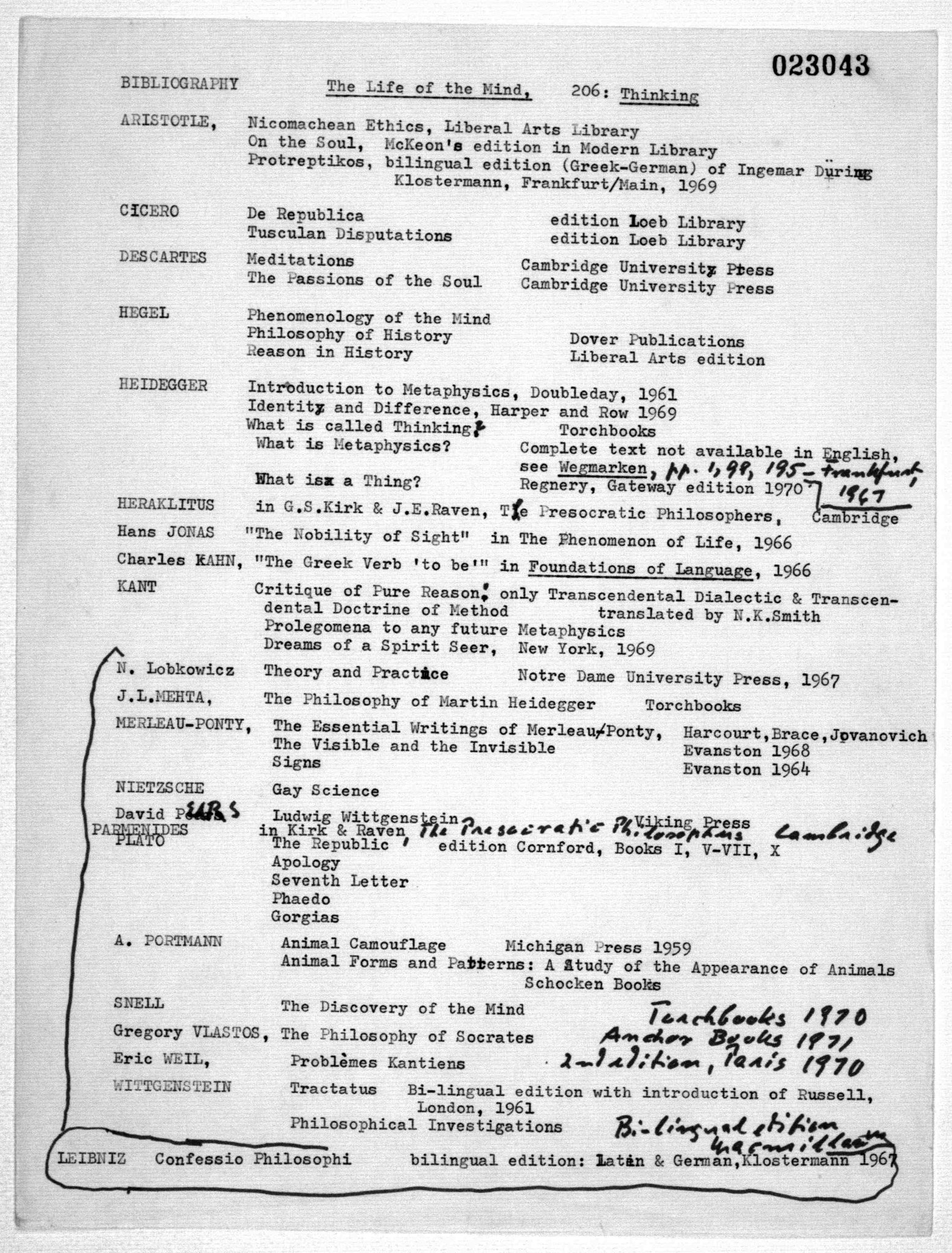

“The Life of the Mind” also appears atop the syllabus, recently posted by Arendt biographer Samantha Rose Hill, for “206: Thinking,” a class Arendt taught in 1974 at the New School for Social Research. Encompassing a range of philosophers from Aristotle, Cicero, and Plato to Nietzsche, Wittgenstein, and Heidegger (a figure with whom she could claim a more intimate familiarity than most), it seems to have offered a reasonably thorough survey of the figures we think of when we think of thinking itself.

Arendt had apparently adapted some of the content from the 1973–1974 Gifford Lectures she had delivered in Aberdeen, which themselves condensed material from her courses on “Basic Moral Propositions,” “Thinking,” “The History of the Will,” and “Kant’s Critique of Judgment.”

Arendt’s teaching at the New School, in “Thinking” and other courses like “Philosophy of the Mind,” sheds a bit of light on what would have gone into the unwritten third volume of The Life of the Mind, or at least into the arc of the trilogy as a whole. Volumes one and two, drafts of which she put into circulation among her graduate students, were called Thinking and Willing; the third was to have been Judging, by far the thorniest mental activity of the set. It would be worth hearing from former New School students of the mid-seventies who retain any classroom memories of what she had to say on the subject. As for the rest of us, we can at least still do all the reading for “Thinking,” then judge for ourselves. You can find the syllabus on the Library of Congress website.

Related content:

Take Hannah Arendt’s Final Exam for Her 1961 Course “On Revolution”

Hannah Arendt Explains How Totalitarian Regimes Arise–and How We Can Prevent Them

Watch Hannah Arendt’s Final Interview (1973)

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities and the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles. Follow him on the social network formerly known as Twitter at @colinmarshall.

This is, disappointingly, not a syllabus it is a bibliography. A syllabus would denote what parts of and in what order the books on the bibliography should be read.