Say you were a fan of Steven Spielberg’s moving coming-of-age drama Empire of the Sun, set in a Japanese internment camp during World War II and starring a young Christian Bale. Say you read the autobiographical novel on which that film is based, written by one J.G. Ballard. Say you enjoyed it so much, you decided to read more of the author’s work, like, say, 1973’s Crash, a novel about people who develop a sexual fetish around wounds sustained in staged automobile accidents. Or you pick up its predecessor, The Atrocity Exhibition, a book William S. Burroughs described as stirring “sexual depths untouched by the hardest-core illustrated porn.” Or perhaps you stumble upon Concrete Island, a warped take on Defoe that strands a wealthy architect and his Jaguar on a highway intersection.

You may experience some dissonance. Who was this Ballard? A realist chronicler of 20th century horrors; perverse explorer of—in Burroughs’ words—“the nonsexual roots of sexuality”; sci-fi satirist of the bleak post-industrial wastelands of modernity? He was all of these, and more. Ballard was a brilliant futurist and his dystopian novels and short stories anticipated the 80s cyberpunk of William Gibson, exploring with a twisted sense of humor what Jean Lyotard famously dubbed in 1979 The Postmodern Condition: a state of ideological, scientific, personal, and social disintegration under the reign of a technocratic, hypercapitalist, “computerized society.” Ballard had his own term for it: “media landscape,” and his dark visions of the future often correspond to the virtual world we inhabit today.

In addition to his fictional creations, Ballard made several disturbingly accurate predictions in interviews he gave over the decades (collected in a book titled Extreme Metaphors). In 1987, with the film adaptation of Empire of the Sun just on the horizon and “his most extreme work Crash re-released in the USA to warmer reaction,” he gave an interview to I‑D magazine in which he predicted the internet as “invisible streams of data pulsing down lines to produce an invisible loom of world commerce and information.” This may not seem especially prescient (see, for example, E.M. Forster’s 1909 “The Machine Stops” for a chilling futuristic scenario much further ahead of its time). But Ballard went on to describe in detail the rise of the Youtube celebrity:

Every home will be transformed into its own TV studio. We’ll all be simultaneously actor, director and screenwriter in our own soap opera. People will start screening themselves. They will become their own TV programmes.

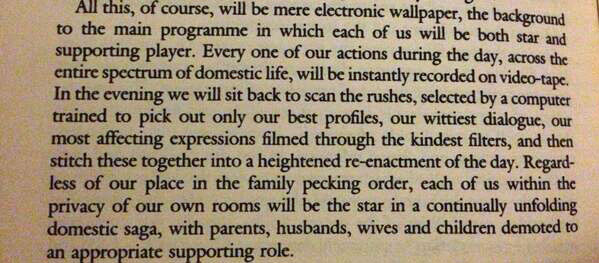

The themes of celebrity obsession and technologically constructed realities resonate in almost all of Ballard’s work and thought, and ten years earlier, in an essay for Vogue, he described in detail the spread of social media and its totalizing effects on our lives. In the technological future, he wrote, “each of us will be both star and supporting player.”

Every one of our actions during the day, across the entire spectrum of domestic life, will be instantly recorded on video-tape. In the evening we will sit back to scan the rushes, selected by a computer trained to pick out only our best profiles, our wittiest dialogue, our most affecting expressions filmed through the kindest filters, and then stitch these together into a heightened re-enactment of the day. Regardless of our place in the family pecking order, each of us within the privacy of our own rooms will be the star in a continually unfolding domestic saga, with parents, husbands, wives and children demoted to an appropriate supporting role.

Though Ballard thought in terms of film and television—and though we ourselves play the role of the selecting computer in his scenario—this description almost perfectly captures the behavior of the average user of Facebook, Instagram, etc. (See Ballard in the interview clip above discuss further “the possibilities of genuinely interactive virtual reality” and his theory of the 50s as the “blueprint” of modern technological culture and the “suburbanization” of reality.) In addition to the Vogue essay, Ballard wrote a 1977 short story called “The Intensive Care Unit,” in which—writes the site Ballardian—“ordinances are in place to prevent people from meeting in person. All interaction is mediated through personal cameras and TV screens.”

So what did Ballard, who died in 2009, think of the post-internet world he lived to see and experience? He discussed the subject in 2003 in an interview with radical publisher V. Vale (who re-issued The Atrocity Exhibition). “Now everybody can document themselves in a way that was inconceivable 30, 40, 50 years ago,” Ballard notes, “I think this reflects a tremendous hunger among people for ‘reality’—for ordinary reality. It’s very difficult to find the ‘real,’ because the environment is totally manufactured.” Like Jean Baudrillard, another prescient theorist of postmodernity, Ballard saw this loss of the “real” coming many decades ago. As he told I‑D in 1987, “in the media landscape it’s almost impossible to separate fact from fiction.”

Related Content:

A 1947 French Film Accurately Predicted Our 21st-Century Addiction to Smartphones

The Very First Film of J.G. Ballard’s Crash, Starring Ballard Himself (1971)

Hear Five JG Ballard Stories Presented as Radio Dramas

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

‘The Outer Limits’ episode ‘O.B.I.T.’ had him beat by some time (1963)

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=L7Cg35uH8fM