“I feel like every single frame of the film is burned into my retina,” said Oscar-winning actress Cate Blanchett about the movie Stalker (1979). “I hadn’t seen anything like it before and I haven’t really seen anything like it since.

Andrei Tarkovsky’s final film in the USSR seems like an unlikely movie to have a devoted, almost cultish, following. It is a dense, multivalent, maddeningly elusive work that has little of the narrative pay-offs of a Hollywood movie. Yet the film is so slippery and so seemingly pliable to an endless number of interpretations that it requires multiple viewings. “I’ve seen Stalker more times than any film except The Great Escape,” wrote novelist and critic Geoff Dyer,” and it’s never quite as I remember. Like the Zone, it’s always changing.”

The movie’s story is simple: a guide, called here a Stalker, takes a celebrated writer and a scientist from a rotting industrial cityscape into a verdant area called The Zone, the site of some undefined calamity which has been cordoned off by rings of razor wire and armed guards. There, one supposedly can have their deepest, darkest desires fulfilled. Yet even if you manage to give the guards a slip, there are still countless subtle traps laid by whatever sentient intelligence that controls the Zone. Rationality is of no help here. One can only progress along a meandering path that can only be followed by intuition.

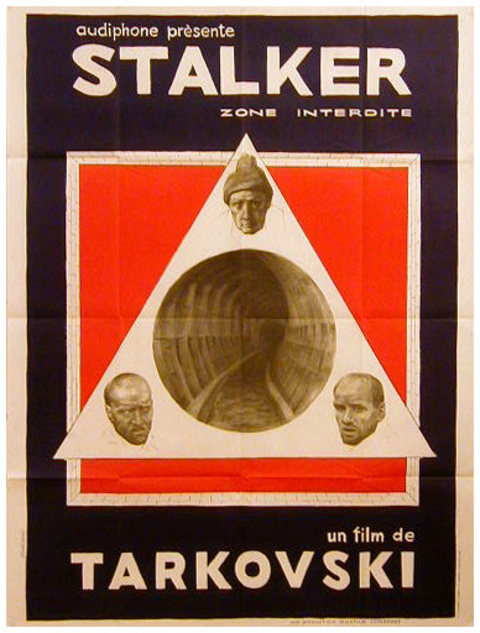

The Stalker, with his shaved head and a perpetually haunted expression on his face, is a sort of holy fool; a man who is both addicted to the strange energy of the Zone and bound to help his fellow man. His clients’ motives, however, are far less altruistic. Once deep in the room, the three engage in a series of philosophical arguments that quickly turns personal.

The movie’s power, however, is not found in traditional dramatics. Instead it’s a cumulative effect of Tarkovsky’s hypnotic pace, his philosophical commentary and perhaps most of all his imagery. Shot with smudgy, almost completely desaturated colors, the world outside the Zone seems to be a grim, dismal place – as if Tarkovsky were trying to evoke the industrial hellscape of Eraserhead by way of Samuel Beckett. (Stalker was in fact shot in an industrial wasteland outside of Tallinn, Estonia, down river from a chemical plant. Exposure to that plant’s runoff might very well have caused the filmmaker’s death.) Inside the Zone, however, the surroundings are lush and colorful, filled with glimpses of inexplicable wonder and beauty.

Stalker screenwriter Arkady Strugatsky once said that the movie was not “a science fiction screenplay but a parable.” The question is, a parable of what? Religious faith? Art? The cinema itself? Reams of paper have been devoted to this question and I’m not offering any theories. Tarkovsky himself, in his book Sculpting Time, wrote “People have often asked me what The Zone is, and what it symbolizes…The Zone doesn’t symbolize anything, any more than anything else does in my films: the zone is a zone, it’s life.”

Of course, that explanation does little to explain the film’s startling, utterly cryptic final minutes.

Above, you can watch the film online, thanks to Mosfilm. You can also find other Tarkovsky films in the Relateds below.

Related Content:

Watch Andrei Tarkovsky’s Films Free Online: Stalker, The Mirror & Andrei Rublev

Andrei Tarkovsky’s Very First Films: Three Student Films, 1956–1960

Andrei Tarkovsky Answers the Essential Questions: What is Art & the Meaning of Life?

Jonathan Crow is a Los Angeles-based writer and filmmaker whose work has appeared in Yahoo!, The Hollywood Reporter, and other publications. You can follow him at @jonccrow. And check out his blog Veeptopus, featuring lots of pictures of vice presidents with octopuses on their heads. The Veeptopus store is here.

Leave a Reply