The very words “Ellis Island” bring to mind a host of sepia-toned images, shaped by both American historical fact and national myth. Officers employed there really did inspect the eyelids of new arrivals with buttonhooks, for example, but they didn’t actually make a policy of changing their names, however foreign they sounded. You can learn this and much else besides by paying a visit to the National Immigration Museum on Ellis Island, which opened in 1990, 36 years after the closure of the immigrant inspection and processing station itself. But if Frank Lloyd Wright had had his way, you could live on Ellis Island — and what’s more, you’d never need to leave it.

“After Ellis Island was decommissioned in 1954 as the nation’s gateway to the world’s huddled masses, the U.S. General Services Administration (GSA) chose an all-American path: opening the site to developers,” write Sam Lubell and Greg Goldin at the Gotham Center for New York City History. When NBC radio and television announcer Jerry Damon and director Elwood Doudt pitched to Wright the ambitious idea of redeveloping the disused island into a “completely self-contained city of the future,” the architect replied that the project was “virtually made to order for me.” Alas, Wright died just before they could all meet and hammer out the details, but not before he’d drawn up a preliminary but vivid plan.

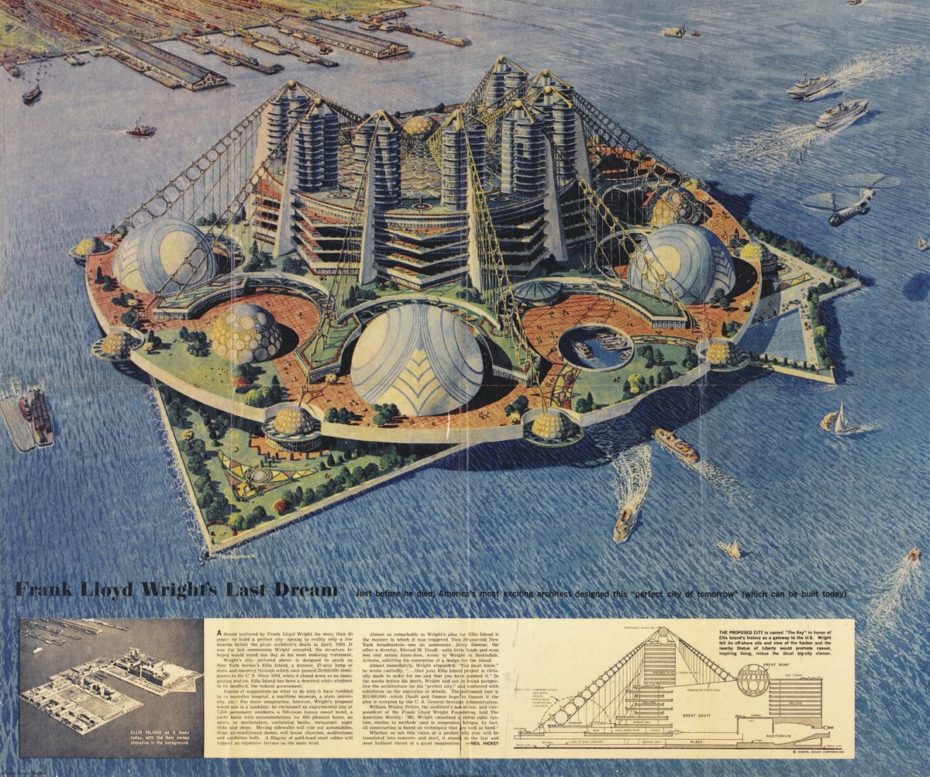

Damon and Doudt carried on with what the late Wright has named the “Key Project.” “Its Jules Verne-esque design, based on Wright’s sketches, was resolutely futuristic,” write Lubell and Goldin. A “circular podium” on the island would support “apartments for 7,500 residents, rising like a stack of offset, alternating dishes. Above these dwelling floors, and separated by sundecks, would be a crescent of seven corrugated, candlestick-shaped towers containing more apartments and a 500-room hotel.” At the center of it all, Wright placed “a huge globe, seemingly pockmarked by eons of meteor collisions, and held aloft by plastic canopies protecting the plazas below.”

It’s easy to imagine the execution of this Space Age urban utopia not quite living up to Wright’s vision — and, indeed, to imagine it having fallen by now into just as thorough a state of dilapidation as did Ellis Island’s original buildings. But it’s also fascinating to consider what could have been Wright’s final commission as the acme of the evolution of his thinking about the urban space itself. A quarter-century earlier, he’d been obsessed with the quasi-rural development he called Broadacre City; just a few years before his death, he came up with the Illinois Mile-High Tower, a megastructure that would practically have constituted a metropolis in and of itself. The Key Project, as Damon and Doudt promoted it, would have offered “casual, inspired living, minus the usual big-city clamor”: the kind of marketing language we hear from developers still today, though not backed by the genius of the most renowned architect in American history.

Related content:

Frank Lloyd Wright Designs an Urban Utopia: See His Hand-Drawn Sketches of Broadacre City (1932)

Why Frank Lloyd Wright Designed a Gas Station in Minnesota (1958)

Portraits of Ellis Island Immigrants Arriving on America’s Welcoming Shores Circa 1907

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities, the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.

A seminal work that captures the essence of architectural heritage, Segregated Architecture is sure to inspire and educate readers for generations to come.

With its meticulous scholarship and powerful storytelling, Segregated Architecture challenges us to rethink our understanding of the built environment and its social implications.