Westerners tend to think of Japan as a land of high-speed trains, expertly prepared sushi and ramen, auteur films, brilliant animation, elegant woodblock prints, glorious old hotels, sought-after jazz-records, cat islands, and ghost towns. The last of those has, of course, not been shown to harbor literal wraiths and spirits. But if that sort of thing happens to be what you’re looking for, Japan’s long history offers up a wealth of mythological chimeras whose form, behavior, and sheer numbers exceed any of our expectations. Welcome to the supernatural realm of the shapeshifting, good- and bad-luck-bringing, trick-playing yōkai.

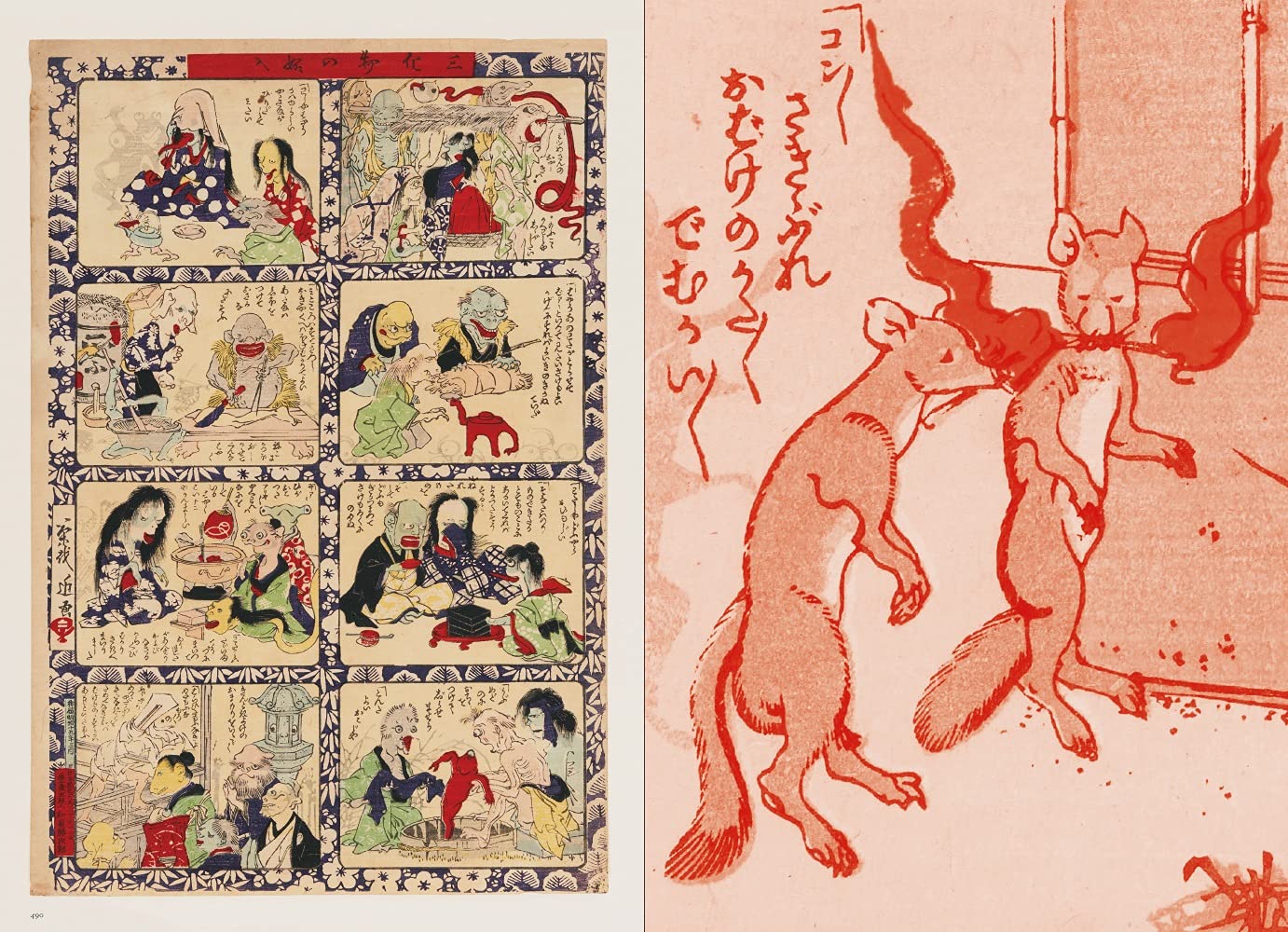

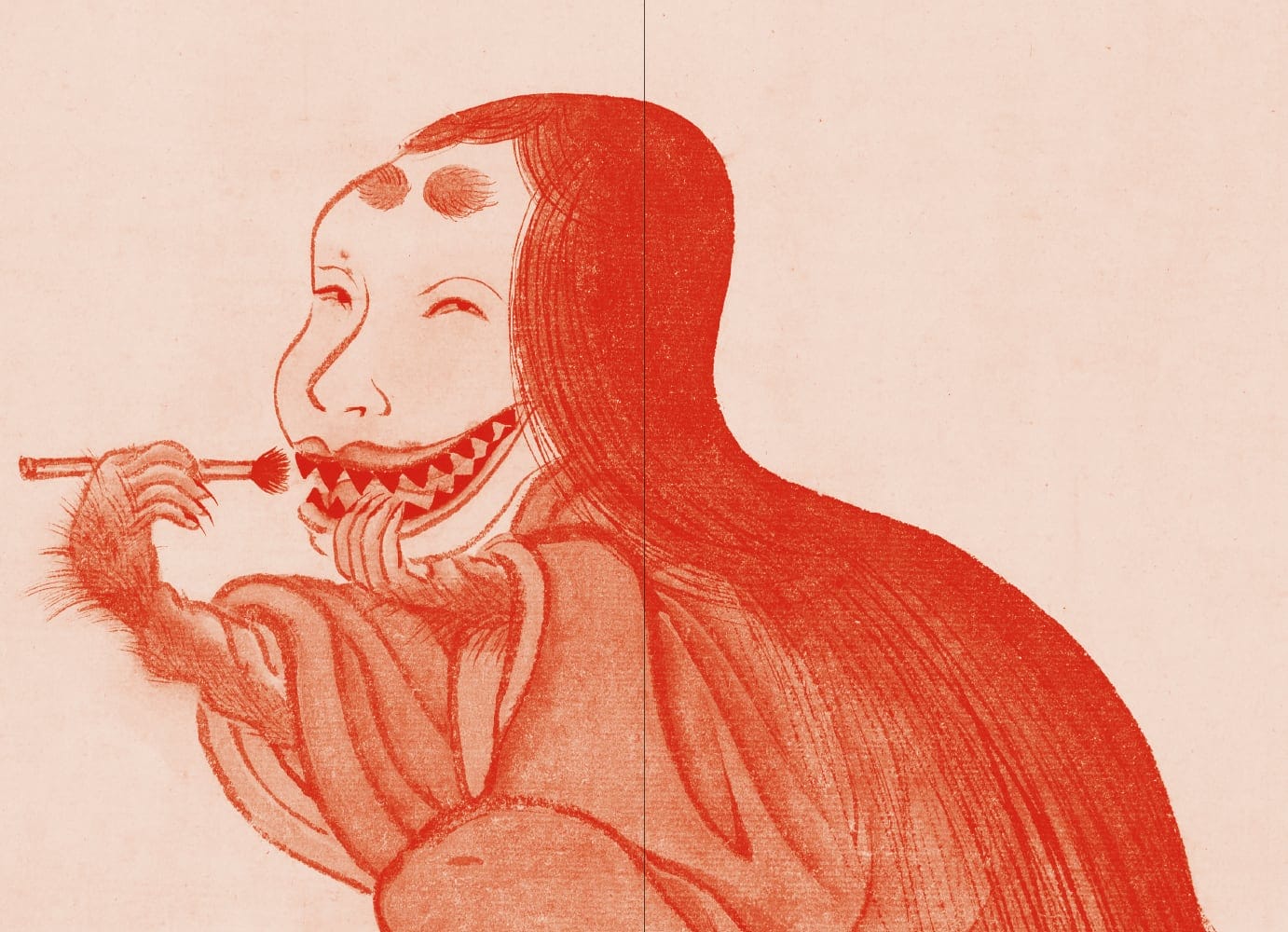

“Translating to ‘strange apparition,’ the Japanese word yōkai refers to supernatural beings, mutant monsters, and spirits,” writes Colossal’s Grace Ebert. “Mischievous, generous, and sometimes vengeful, the creatures are rooted in folklore and experienced a boom during the Edo period when artists would ascribe inexplicable phenomena to the unearthly characters.”

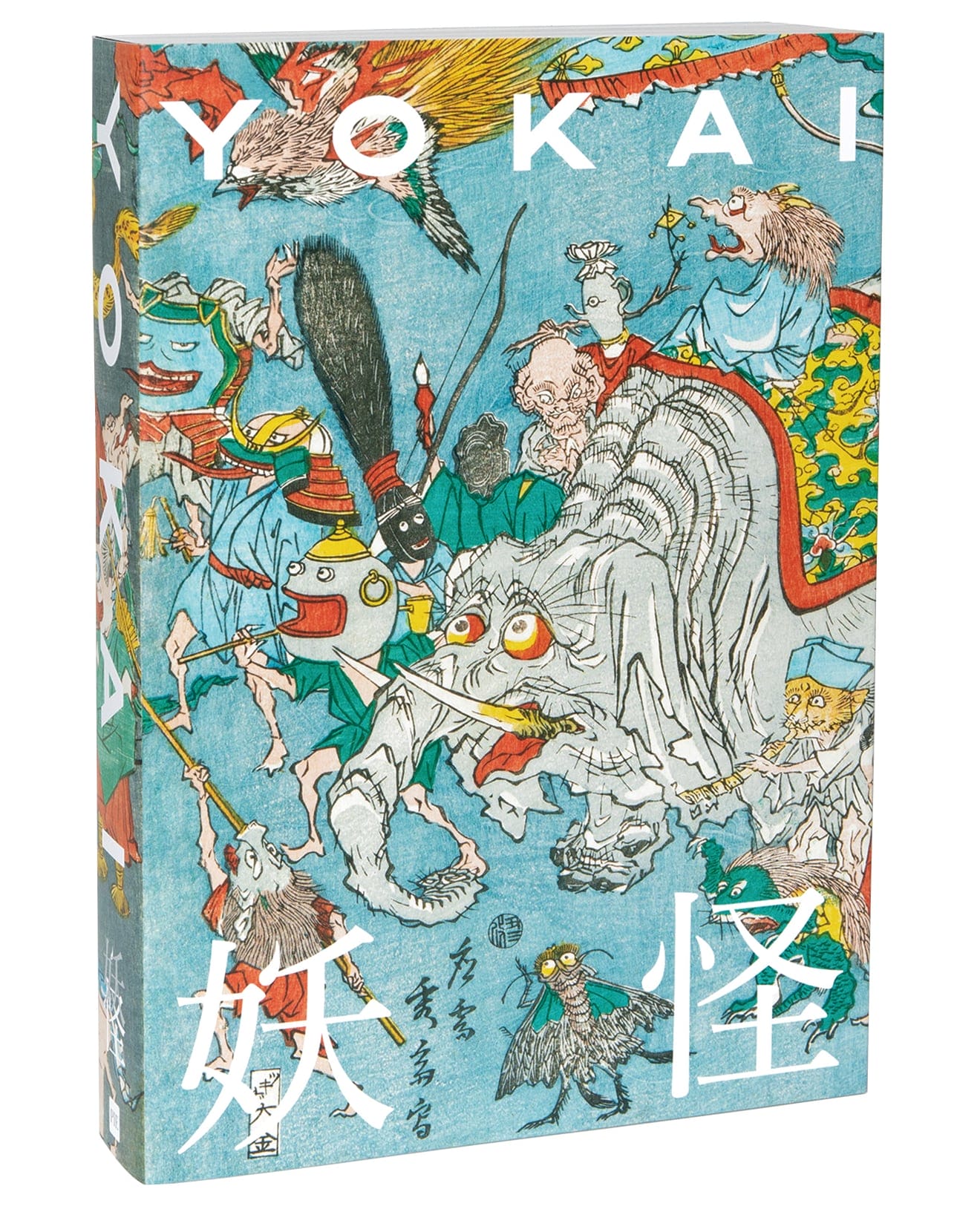

Hiroshima Prefecture’s Miyoshi Mononoke Museum, whose opening we announced here on Open Culture in 2019, “houses the largest yōkai collection in the world with more than 5,000 works, and a book recently published by PIE International showcases some of the most iconic and bizarre pieces from the institution.”

Written by ethnologist Yumoto Koichi, a yōkai expert whose donations constitute most of the Miyoshi Mononoke Museum’s collection, the 500-page YOKAI offers “the rare experience of seeing the brushwork of Edo-era painters like Tsukioka Yoshitoshi,” whom we’ve featured here as Japan’s last great woodblock artist. Poised between the human and animal kingdoms, reflecting the ways of the past as well as the forces of nature, yōkai would seem to belong entirely to the tales of a bygone age. But in fact, many of them have joined the canon since Tsukioka’s time, having emerged from haunted-school rumors, the fertile imaginations of manga artists, and even video games. Whether to accept these “modern yōkai” has been a matter of some debate, but as Japanese popular culture has long shown us, every age needs its own monsters.

via Colossal

Related content:

The First Museum Dedicated to Japanese Folklore Monsters Is Now Open

When a UFO Came to Japan in 1803: Discover the Legend of Utsuro-bune

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities, the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.

Leave a Reply