It’s time to forget nearly everything you know about Rudolph the Red-Nosed Reindeer…at least as established by the 1964 Rankin/Bass stop motion animated television special.

You can hang onto the source of Rudolph’s shame and eventual triumph — the glowing red nose that got him bounced from his playmates’ reindeer games before saving Christmas.

Lose all those other now-iconic elements — the Island of Misfit Toys, long-lashed love interest Clarice, the Abominable Snow Monster of the North, Yukon Cornelius, Sam the Snowman, and Hermey the aspirant dentist elf.

As originally conceived, Rudolph (runner up names: Rollo, Rodney, Roland, Roderick and Reginald) wasn’t even a resident of the North Pole.

He lived with a bunch of other reindeer in an unremarkable house somewhere along Santa’s delivery route.

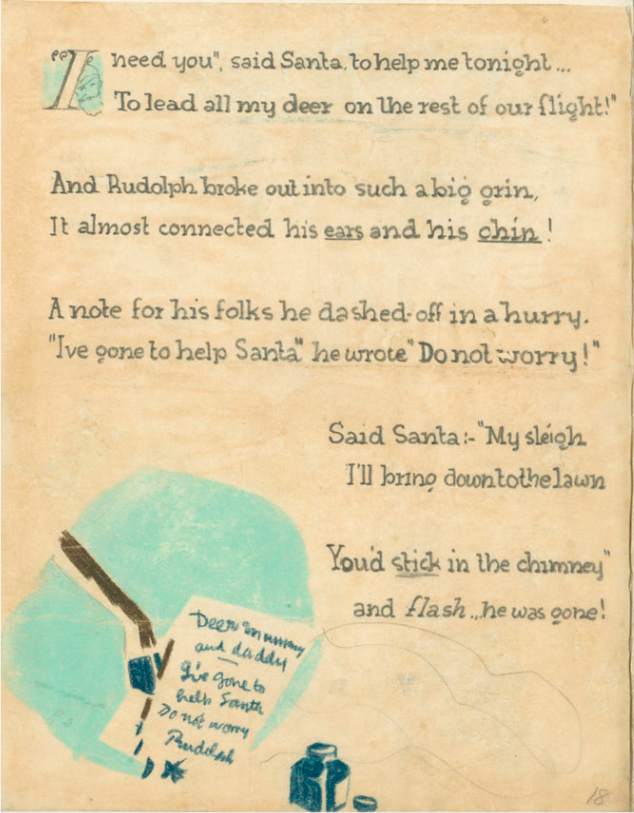

Santa treated Rudolph’s household as if it were a human address, coming down the chimney with presents while the occupants were asleep in their beds.

To get to Rudolph’s origin story we must travel back in time to January 1939, when a Montgomery Ward department head was already looking for a nationwide holiday promotion to draw customers to its stores during the December holidays.

He settled on a book to be produced in house and given away free of charge to any child accompanying their parent to the store.

Copywriter Robert L. May was charged with coming up with a holiday narrative starring an animal similar to Ferdinand the Bull.

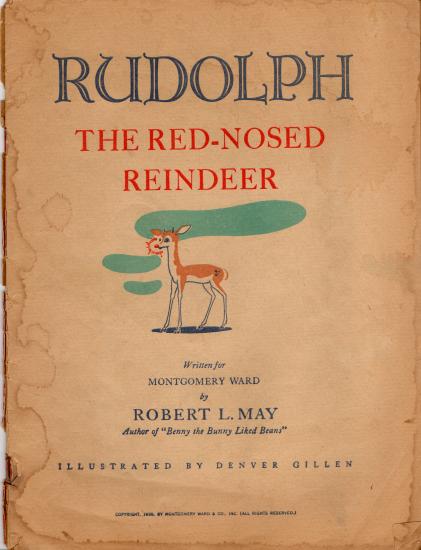

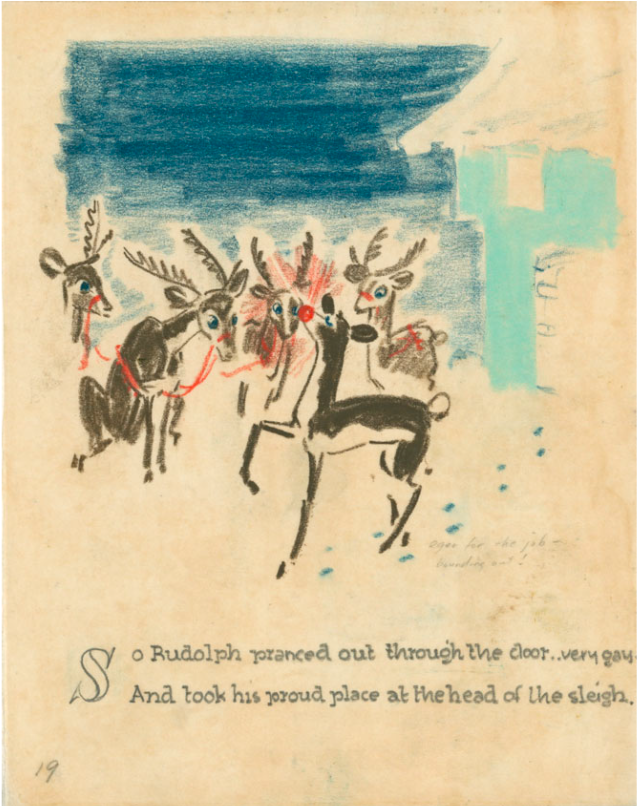

After giving the matter some thought, May tapped Denver Gillen, a pal in Montgomery Ward’s art department, to draw his underdog hero, an appealing-looking young deer with a red nose big enough to guide a sleigh through thick fog.

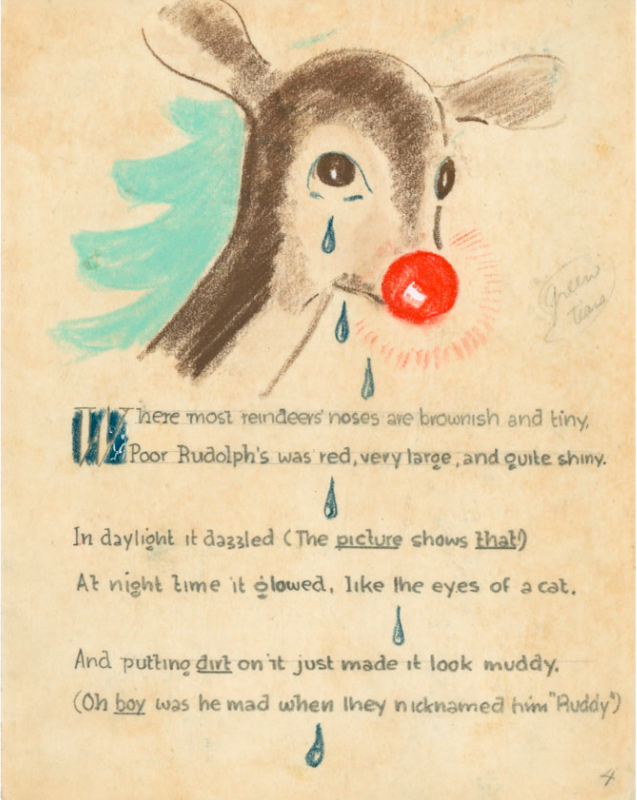

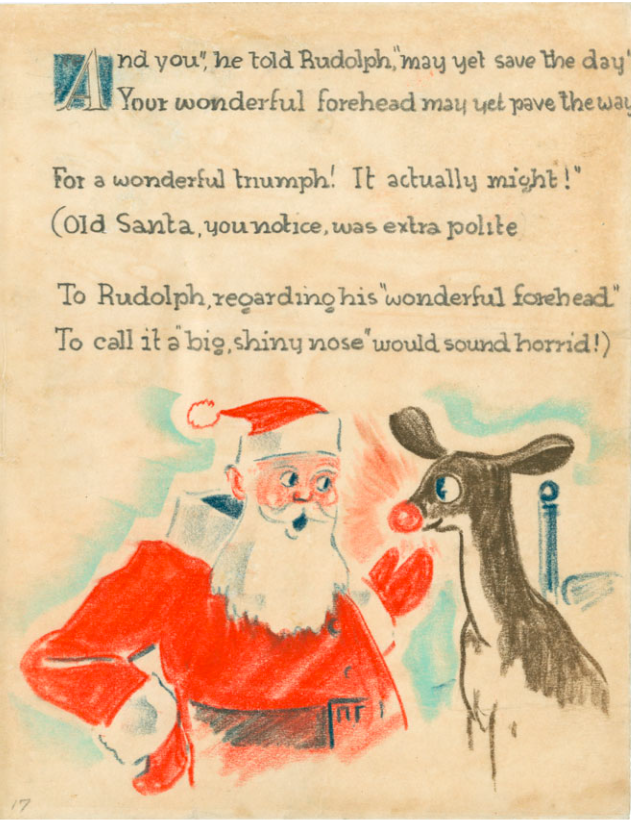

(That schnozz is not without controversy. Prior to Caitlin Flanagan’s 2020 essay in the Atlantic chafing at the television special’s explicitly cruel depictions of othering the oddball, Montgomery Ward fretted that customers would interpret a red nose as drunkenness. In May’s telling, Santa is so uncomfortable bringing up the true nature of the deer’s abnormality, he pretends that Rudolph’s “wonderful forehead” is the necessary headlamp for his sleigh…)

On the strength of Gillen’s sketches, May was given the go-ahead to write the text.

His rhyming couplets weren’t exactly the stuff of great children’s literature. A sampling:

Twas the day before Christmas, and all through the hills,

The reindeer were playing, enjoying the spills.

Of skating and coasting, and climbing the willows,

And hopscotch and leapfrog, protected by pillows.

___

And Santa was right (as he usually is)

The fog was as thick as a soda’s white fizz

—-

The room he came down in was blacker than ink

He went for a chair and then found it a sink!

No matter.

May’s employer wasn’t much concerned with the artfulness of the tale. It was far more interested in its potential as a marketing tool.

“We believe that an exclusive story like this aggressively advertised in our newspaper ads and circulars…can bring every store an incalculable amount of publicity, and, far more important, a tremendous amount of Christmas traffic,” read the announcement that the Retail Sales Department sent to all Montgomery Ward retail store managers on September 1, 1939.

Over 800 stores opted in, ordering 2,365,016 copies at 1½¢ per unit.

Promotional posters touted the 32-page freebie as “the rollickingest, rip-roaringest, riot-provokingest, Christmas give-away your town has ever seen!”

The advertising manager of Iowa’s Clinton Herald formally apologized for the paper’s failure to cover the Rudolph phenomenon — its local Montgomery Ward branch had opted out of the promotion and there was a sense that any story it ran might indeed create a riot on the sales floor.

His letter is just but one piece of Rudolph-related ephemera preserved in a 54-page scrapbook that is now part of the Robert Lewis May Collection at Dartmouth, May’s alma mater.

Another page boasts a letter from a boy named Robert Rosenbaum, who wrote to thank Montgomery Ward for his copy:

I enjoyed the book very much. My sister could not read it so I read it to her. The man that wrote it done better than I could in all my born days, and that’s nine years.

The magic ingredient that transformed a marketing scheme into an evergreen if not universally beloved Christmas tradition is a song …with an unexpected side order of corporate generosity.

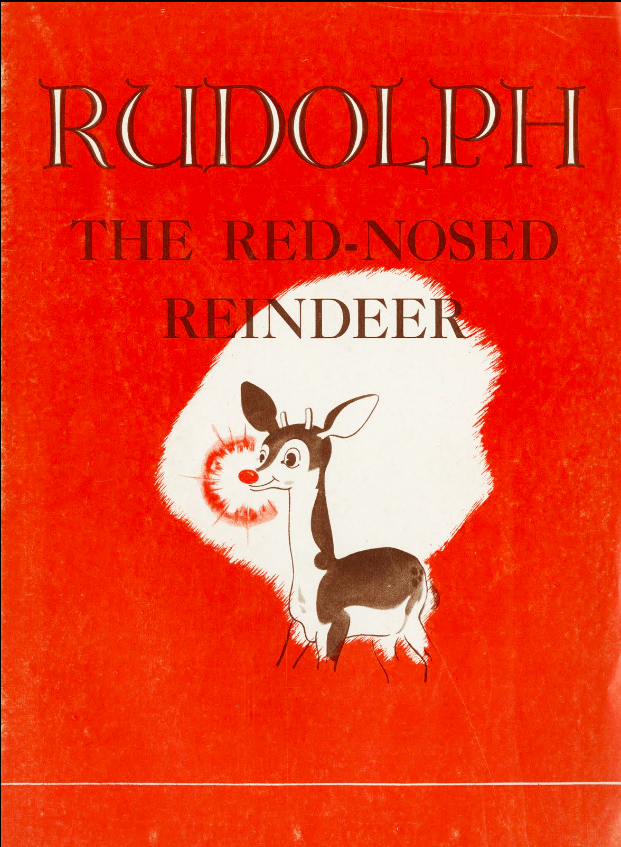

May’s wife died of cancer when he was working on Rudolph, leaving him a single parent with a pile of medical bills. After Montgomery Ward repeated the Rudolph promotion in 1946, distributing an additional 3,600,000 copies, its Board of Directors voted to ease his burden by granting him the copyright to his creation.

Once he held the reins to the “most famous reindeer of all”, May enlisted his songwriter brother-in-law, Johnny Marks, to adapt Rudolph’s story.

The simple lyrics, made famous by singing cowboy Gene Autry’s 1949 hit recording, provided May with a revenue stream and Rankin/Bass with a skeletal outline for its 1964 stop-animation special.

Screenwriter Romeo Muller, the driving force behind the Island of Misfit Toys, Sam the Snowman, Clarice, et al revealed that he would have based his teleplay on May’s original book, had he been able to find a copy.

Read a close-to-final draft of Robert L. May’s Rudolph the Red-Nosed Reindeer, illustrated by Denver Gillen here.

Bonus content: Max Fleischer’s animated Rudolph The Red-Nosed Reindeer from 1948, which preserves some of May’s original text.

Related Content

Hear Neil Gaiman Read A Christmas Carol Just Like Charles Dickens Read It

Hear Paul McCartney’s Experimental Christmas Mixtape: A Rare & Forgotten Recording from 1965

– Ayun Halliday is the Chief Primatologist of the East Village Inky zine and author, most recently, of Creative, Not Famous: The Small Potato Manifesto and Creative, Not Famous Activity Book. Follow her @AyunHalliday.

Thank you for the article. I love stories-behind-the-music. Incorporating the book excerpts was especially enjoyable since I had never seen this original version. Thanks!