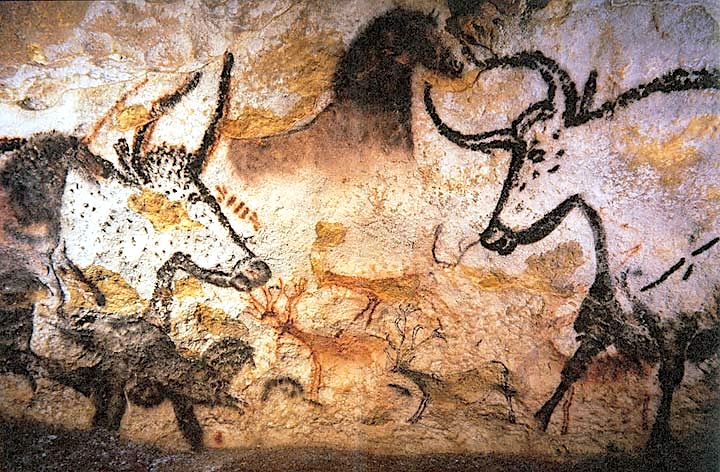

Image via Wikimedia Commons

The Lascaux Caves enjoyed a quiet existence for some 17,000 years.

Then came the summer of 1940, when four teens investigated what seemed to be a fox’s den on a hill near Montignac, hoping it might lead to an underground passageway of local legend.

Once inside, they discovered the paintings that have intrigued us ever since, expanding our understanding of prehistoric art and human origins, and causing us to speculate on things we’ll never have an answer to.

The boys’ teacher reached out to several prehistorians, who authenticated the figures, arranged for them to be photographed and sketched, and collected a number of bone and flint artifacts from the caves’ floors.

By 1948, excavations and artificial lights rendered the caves accessible to visitors, who arrived in droves — as many as 1,800 in a single day.

Less than 20 years later, The Collector’s Rosie Lesso writes, the caves were in crisis, and permanently closed to tourism:

…the heat, humidity and carbon dioxide of all those people crammed into the dark and airless cave was causing an imbalance in the cave’s natural ecosystem, leading to the overgrowth of molds and funguses that threatened to obliterate the prehistoric paintings.

The lights that had helped visitors get an eyeful of the paintings caused fading and discoloration that threatened their very existence.

Declaring this major attraction off limits was the right move, and those who make the journey to the area won’t leave entirely disappointed. Lascaux IV, a painstaking replica that opened to the public in 2016, offers even more verisimilitude than the previous model, 1983’s Lascaux II.

A handful of researchers and maintenance workers are still permitted inside the actual caves, now a UNESCO World Heritage site, but human presence is limited to an annual total of 800 hours, and everyone must be properly outfitted with sterile white overalls, plastic head coverings, latex gloves, double shoe covers, and LED forehead lamps with which to view the paintings.

The rest of us rabble can get a healthy virtual taste of these visitors’ experience thanks to the digital Lascaux collection that the National Archeology Museum created for the Ministry of Culture.

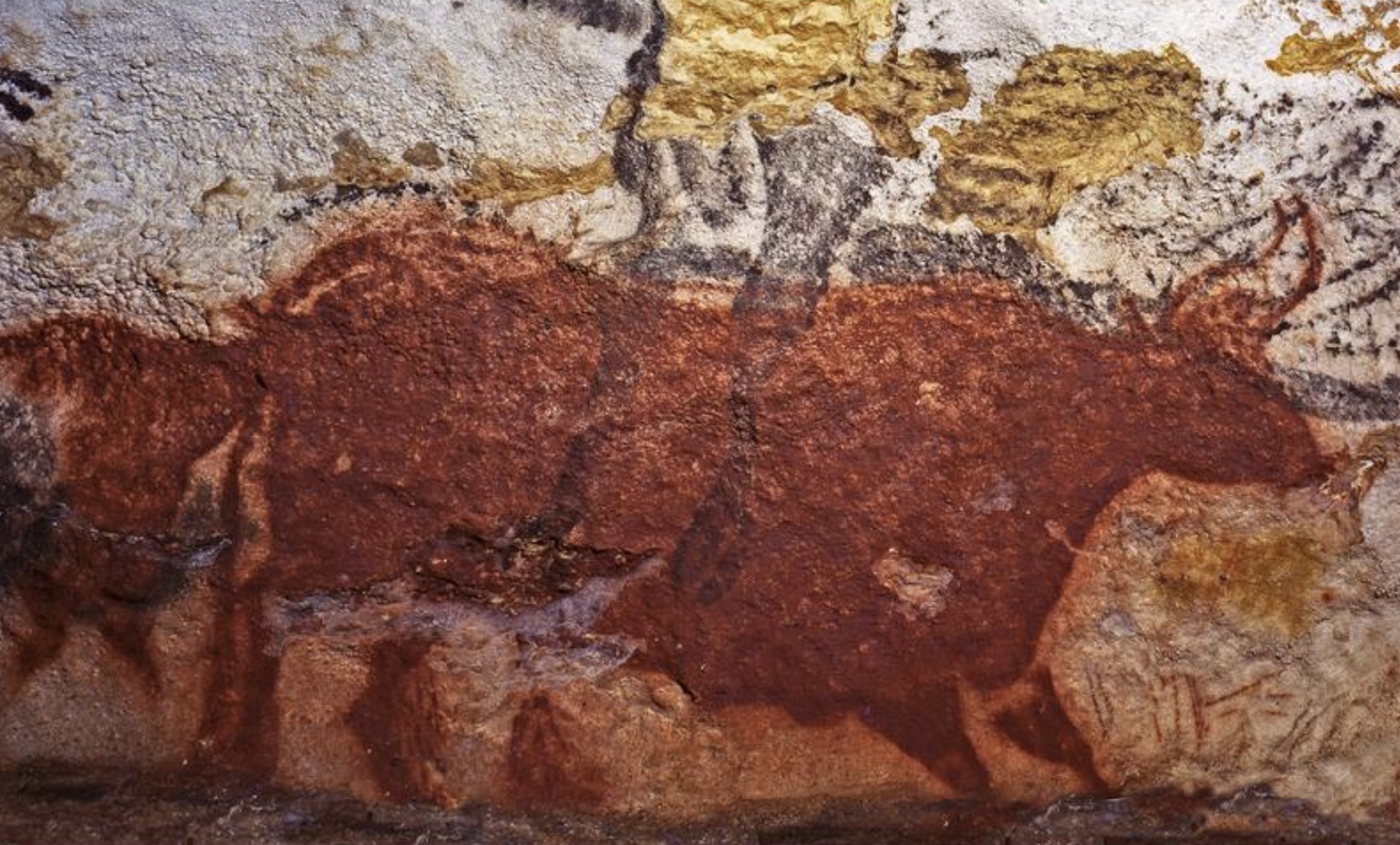

An interactive tour offers close-up views of the famous paintings, with titles to orient the viewer as to the particulars of what and where — for example “red cow followed by her calf” in the Hall of the Bulls.

Click the button in the lower left for a more in-depth expert description of the element being depicted:

The flat red color used for the silhouette is of a uniformity that is seldom attained, which implies a repeated gesture starting from the same point, with complementary angles of projection of pigments. The outlines have been created with a stencil, and only the hindquarters, horns and the line of the back have been laid down with a brush…The fact that the artist used the same pigment for both figures without any pictorial transition between them indicates that the fusion of the two silhouettes was intentional, indicative of the connection between the calf and its mother. This duo was born of the same gesture, and the image of the offspring is merely the graphic extension of that of its mother.

The interactive virtual tour is further complimented by a trove of historic photographs and interviews, geological context, conservation updates and anthropological interpretations suggesting the paintings had a function well beyond visual art.

Begin your virtual interactive visit to the Lascaux Cave here.

Related Content

Was a 32,000-Year-Old Cave Painting the Earliest Form of Cinema?

Algerian Cave Paintings Suggest Humans Did Magic Mushrooms 9,000 Years Ago

40,000-Year-Old Symbols Found in Caves Worldwide May Be the Earliest Written Language

– Ayun Halliday is the Chief Primatologist of the East Village Inky zine and author, most recently, of Creative, Not Famous: The Small Potato Manifesto and Creative, Not Famous Activity Book. Follow her @AyunHalliday.

Thank you