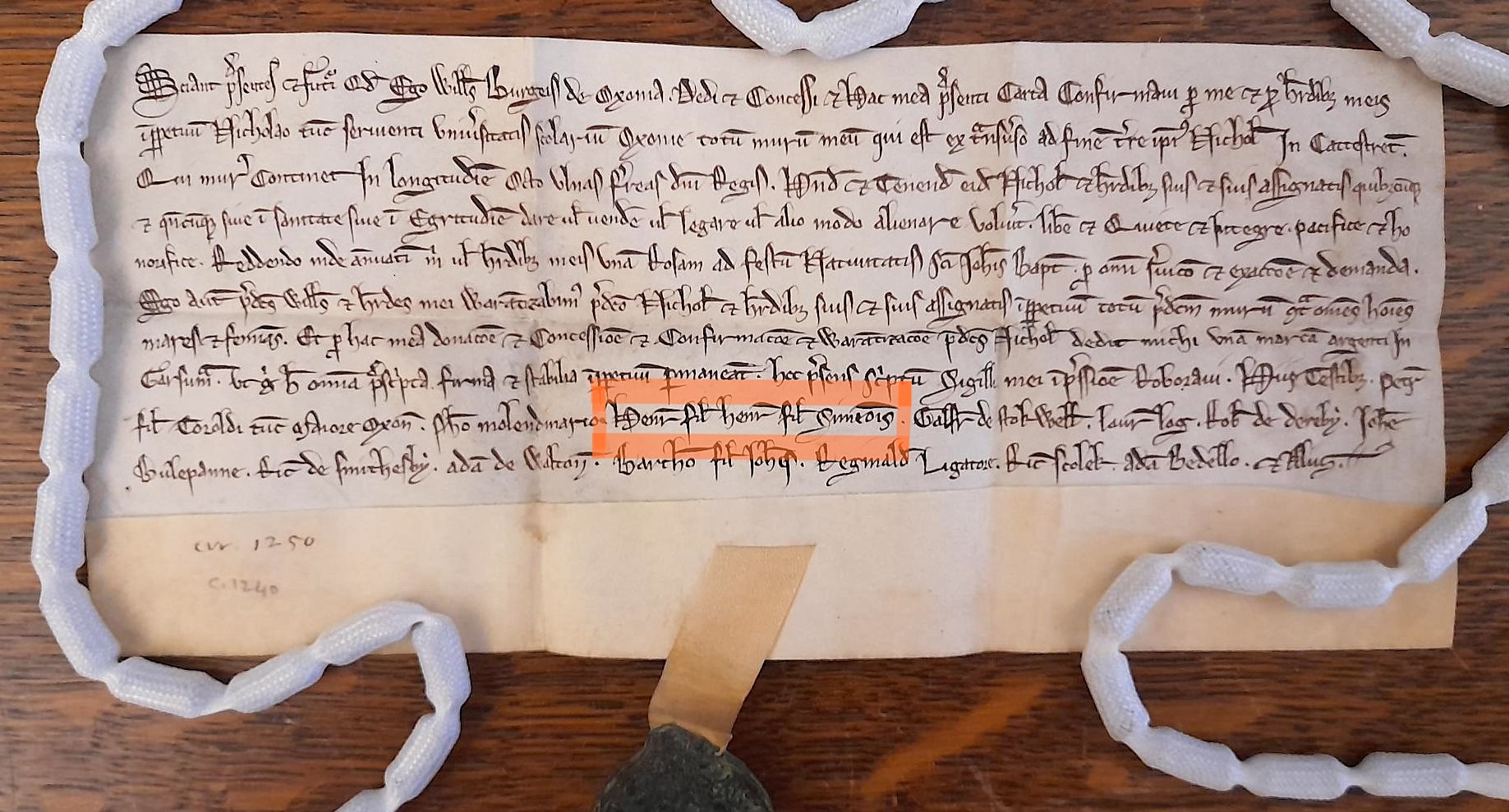

Image via The Bodleian Library

If you were to ask a certain kind of Englishman what sets his homeland apart from the rest of the world, he might point to the strength of its traditions. And what holds true for England itself holds even truer for its most renowned institutions, especially its most prestigious universities. Those who dream of attending Oxford dream not least of its distinctive traditions: from the relatively frequent Formal Hall, to the various ceremonial rituals on Ascension Day, to the Mallard Song sung just once per century by the elites of All Souls College, dating back to that college’s foundation in 1438— which was still long after the time of Oxford’s ultimate persona non grata, a long-mysterious figure named Henry Symeonis.

As recently as the time of Dickens (or at least the era in which he set his novels), Bachelors of Arts students turning Master of Arts students at Oxford were, according to the blog of the Archives and Manuscripts at the Bodleian Library, “required to swear that they would observe the University’s statutes, privileges, liberties and customs, as you might expect; and not to lecture elsewhere, or resume their bachelor studies after getting their MA.” But they “also had to swear that they would never agree to the reconciliation of Henry Symeonis,” whoever that was. “Nowhere in the statutes did it explain who this Henry Symeonis (or Simeonis) was, what he was supposed to have done or why those getting their MAs should never agree to be reconciled with him.”

The clause in question came up for review in the early 1650s, but “even by that time, one suspects that the oath was of such antiquity that no-one knew anything about it and it was thought best to leave it be.” Not until 1912 did Reginald Lane Poole, Keeper of the University Archives, determine that Symeonis was the son of “a very wealthy townsman of Oxford.” In 1242, “he and a number of other men of the town of Oxford were found guilty of murdering a student of the University. Henry and his accomplices were fined £80 by King Henry III in May 1242 and were made to leave Oxford as a result.” Two decades after the murder, Henry III issued Symeonis (who had, in any case, long since returned to town) an official pardon.

“The Government was aware of the volatile relationship between town and gown and was concerned, in 1264, at the prospect of the University leaving Oxford in protest if Henry was allowed to return.” What seems to have happened is that “Henry Symeonis had bought the King’s pardon and his permission to return to Oxford. The King was willing to allow his return if the University agreed to it. But the University refused and chose to ignore the King’s order” — and even “gave Henry Symeonis the unique honor of being named in its own statutes, making the University’s dislike of him official and perpetual.” There his name stayed, receiving the sworn enmity of five and a half centuries’ worth of Oxford students, until the removal of the relevant oath in 1827. “No background information nor reason for the decision is recorded,” notes the Bodleian’s blog, possibly because “nobody knew exactly what they were abolishing.”

via Archives and Manuscripts at the Bodleian Library

Related Content:

New Interactive “Murder Map” Reveals the Meanest Streets of Medieval London

Oxford University Presents the 550-Year-Old Gutenberg Bible in Spectacular, High-Res Detail

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities, the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.

Leave a Reply