As Lisa Simpson once memorably remarked, “I can see the music.”

Pretty much anyone can these days.

Just switch on your device’s audio visualizer.

That wasn’t the case in the 1940s, when psychologist Cecil A. Stokes used chemistry and polarized light to invent soothing abstract music videos, a sort of cinematic synesthesia experiment such as can be seen above, in his only known surviving Auroratone.

(The name was suggested by Stokes’ acquaintance, geologist, Arctic explorer and Catholic priest, Bernard R. Hubbard, who found the result reminiscent of the Aurora Borealis.)

The trippy visuals may strike you as a bit of an odd fit with Bing Crosby’s cover of the sentimental crowdpleaser “Oh Promise Me,” but traumatized WWII vets felt differently.

Army psychologists Herbert E. Rubin and Elias Katz’s research showed that Auroratone films had a therapeutic effect on their patients, including deep relaxation and emotional release.

The music surely contributed to this positive outcome. Other Auroratone films featured “Moonlight Sonata,” “Clair de Lune,” and an organ solo of “I Dream of Jeannie with the Light Brown Hair.”

Drs. Rubin and Katz reported that patients reliably wept during Auroratones set to “The Lost Chord,” “Ave Maria,” and “Home on the Range” — another Crosby number.

In fact, Crosby, always a champion of technology, contributed recordings for a full third of the fifteen known Auroratones free of charge and footed the bill for overseas shipping so the films could be shown to soldiers on active duty and medical leave.

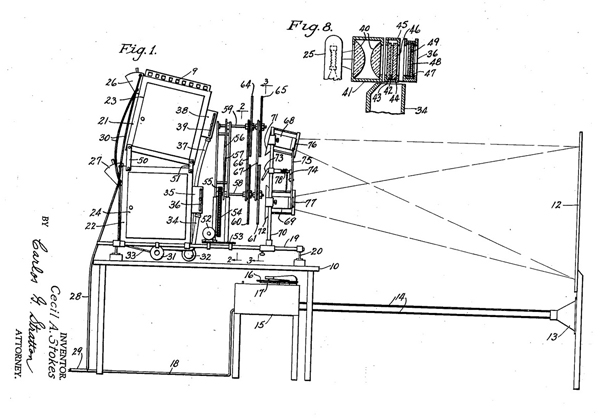

Technophile Crosby was well positioned to understand Stokes’ patented process and apparatus for producing musical rhythm in color — aka Auroratones — but those of us with a shakier grasp of STEM will appreciate light artist John Sonderegger’s explanation of the process, as quoted in filmmaker and media conservator Walter Forsberg’s history of Auroratones for INCITE Journal of Experimental Media:

[Stokes’] procedure was to cut a tape recorded melody into short segments and splice the resulting pieces into tape loops. The audio signal from the first loop was sent to a radio transmitter. The radio waves from the radio transmitter were confined to a tube and focused up through a glass slide on which he had placed a chemical mixture. The radio waves would interact with the solution and trigger the formation of the crystals. In this way each slide would develop a shape interpretive of the loop of music it had been exposed to. Each loop, in sequence, would be converted to a slide. Eventually a set of slides would be completed that was the natural interpretation of the complete musical melody.

Vets suffering from PTSD were not the only ones to embrace these unlikely experimental films.

Patients diagnosed with other mental disorders, youthful offenders, individuals plagued by chronic migraines, and developmentally delayed elementary schoolers also benefited from Auroratones’ soothing effects.

The general public got a taste of the films in department store screenings hyped as “the nearest thing to the Aurora Borealis ever shown”, where the soporific effect of the color patterns were touted as having been created “by MOTHER NATURE HERSELF.”

Auroratones were also shown in church by canny Christian leaders eager to deploy any bells and whistles that might hold a modern flock’s attention.

The Guggenheim Museum’s brass was vastly less impressed by the Auroratone Foundation of America’s attempts to enlist their support for this “new technique using non-objective art and musical compositions as a means of stimulating the human emotions in a manner so as to be of value to neuro-psychiatrists and psychologists, as well as to teachers and students of both objective and non-objective art.”

Co-founder Hilla Rebay, an abstract artist herself, wrote a letter in which she advised Stokes to “learn what is decoration, accident, intellectual confusion, pattern, symmetry… in art there is conceived law only –never an accident.”

A plan for projecting Auroratones in maternity wards to “do away with the pains of child-birth” appears to have been a similar non-starter.

While only one Auroratone is known to have survived — and its discovery by Robert Martens, curator of Grandpa’s Picture Party, is a fascinating tale unto itself — you can try cobbling together a 21st-century DIY approximation by plugging any of the below tunes into your preferred music playing software and turning on the visualizer:

- Adeste Fidelis, sung by Bing Crosby

- American Prayer by Ginny Simms

- Ave Maria, sung by Bing Crosby with organ accompaniment by Edward Dunstedter

- Clair de Lune, played by Andre Kostalanetz and his orchestra

- Going My Way, sung by Bing Crosby with organ accompaniment by Edward Dunstedter

- Home on the Range, sung by Bing Crosby with organ accompaniment by Edward Dunstedter

- I Dream of Jeannie with the Light Brown Hair, organ solo

- The Lone Star Trail, sung by Bing Crosby

- Prelude to Lonegrin, by the Philadelphia Symphony

- The Lord’s Prayer, sung by John Charles Thomas with music by Albert Hay Malotte

- The Lost Chord organ solo

- Moonlight Sonata, played by Miss April Ayres

- None But the Lonely Heart, by Lawrence Tibbett

- The Old Rugged Cross, sung by the Phil Spitalny all-girl chorus

- Silent Night, sung by Bing Crosby

via Boing Boing / INCITE

Related Content

How the 1968 Psychedelic Film Head Destroyed the Monkees & Became a Cult Classic

The Psychedelic Animated Video for Kraftwerk’s “Autobahn” (1979)

– Ayun Halliday is the Chief Primatologist of the East Village Inky zine and author, most recently, of Creative, Not Famous: The Small Potato Manifesto and Creative, Not Famous Activity Book. Follow her @AyunHalliday.

Leave a Reply