Image by The Wellcome Trust

When researching a famous historical figure, access to their work and materials usually proves to be one of the biggest obstacles. But things are much more difficult for those writing about the life of Marie Curie, the scientist who, along her with husband Pierre, discovered polonium and radium and birthed the idea of particle physics. Her notebooks, her clothing, her furniture (not to mention her lab), pretty much everything surviving from her Parisian suburban house, is radioactive, and will be for 1,500 years or more.

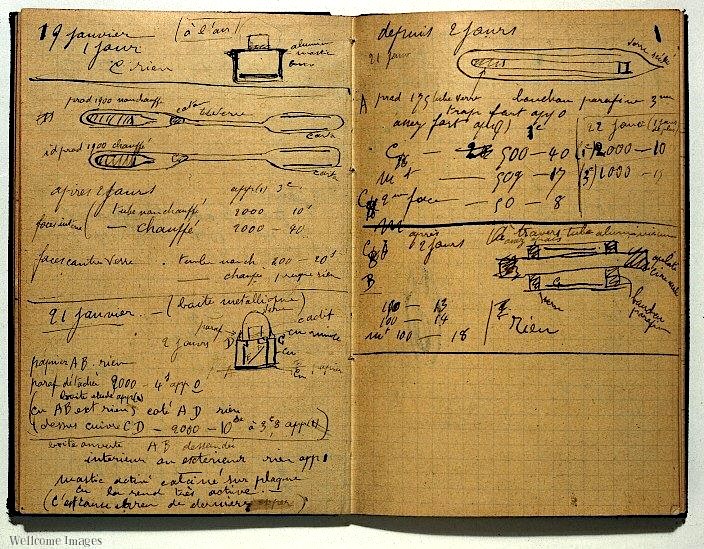

If you want to look at her manuscripts, you have to sign a liability waiver at France’s Bibliotheque Nationale, and then you can access the notes sealed in a lead-lined box. The Curies didn’t know about the dangers of radioactive materials, though they did know about radioactivity. Their research attempted to find out which substances were radioactive and why, and so many dangerous elements–thorium, uranium, plutonium–were just sitting there in their home laboratory, glowing at night, which Curie thought beautiful, “like faint, fairy lights,” she wrote in her autobiography. Marie Curie carried these glowing objects around in her pockets. She and her husband wore standard lab clothing, nothing more.

Marie Curie died at age 66 in 1934, from aplastic anemia, attributed to her radioactive research. The house, however, continued to be used up until 1978 by the Institute of Nuclear Physics of the Paris Faculty of Science and the Curie Foundation. After that it was kept under surveillance, authorities finally now aware of the dangers inside. When many people in the neighborhood noticed high cancer rates among them, as reported in Le Parisien, they blamed the Curie’s home.

The laboratory and the building were decontaminated in 1991, a year after the Curie estate began allowing access to Curie’s notes and materials, which had been removed from the house. A flood of biographies appeared soon after: Marie Curie: A Life by Susan Quinn in 1995, Pierre Curie by Anna Hurwic in 1998, Curie: Le rêve scientifique by Loïc Barbo in 1999, Marie Curie et son laboratoire by Soraya Boudia in 2001, Obsessive Genius: The Inner World of Marie Curie by Barbara Goldsmith in 2005, and Radioactive: Marie and Pierre Curie, a Tale of Love and Fallout by Lauren Redniss in 2011.

Still, passing away at 66 is not too shabby when one has changed the world in the name of science. Marie Curie was the first woman to win a Nobel Prize (1903), the only woman to win it again (1911), the first woman to become a professor at the University of Paris, and the first woman to be entombed (on her own merits) at the Panthéon in Paris. And she managed many of her breakthroughs after the passing of her husband Pierre in 1906–who slipped and fell in the rain on a busy Paris street and was run over by the wheels of a horse-drawn cart.

Note: An earlier version of this post appeared on our site in 2015.

Related Content:

An Animated Introduction to the Life & Work of Marie Curie, the First Female Nobel Laureate

An Animated Introduction to the Life & Work of Marie Curie, the First Female Nobel Laureate

Ted Mills is a freelance writer on the arts who currently hosts the FunkZone Podcast. You can also follow him on Twitter at @tedmills, read his other arts writing at tedmills.com and/or watch his films here.

Leave a Reply