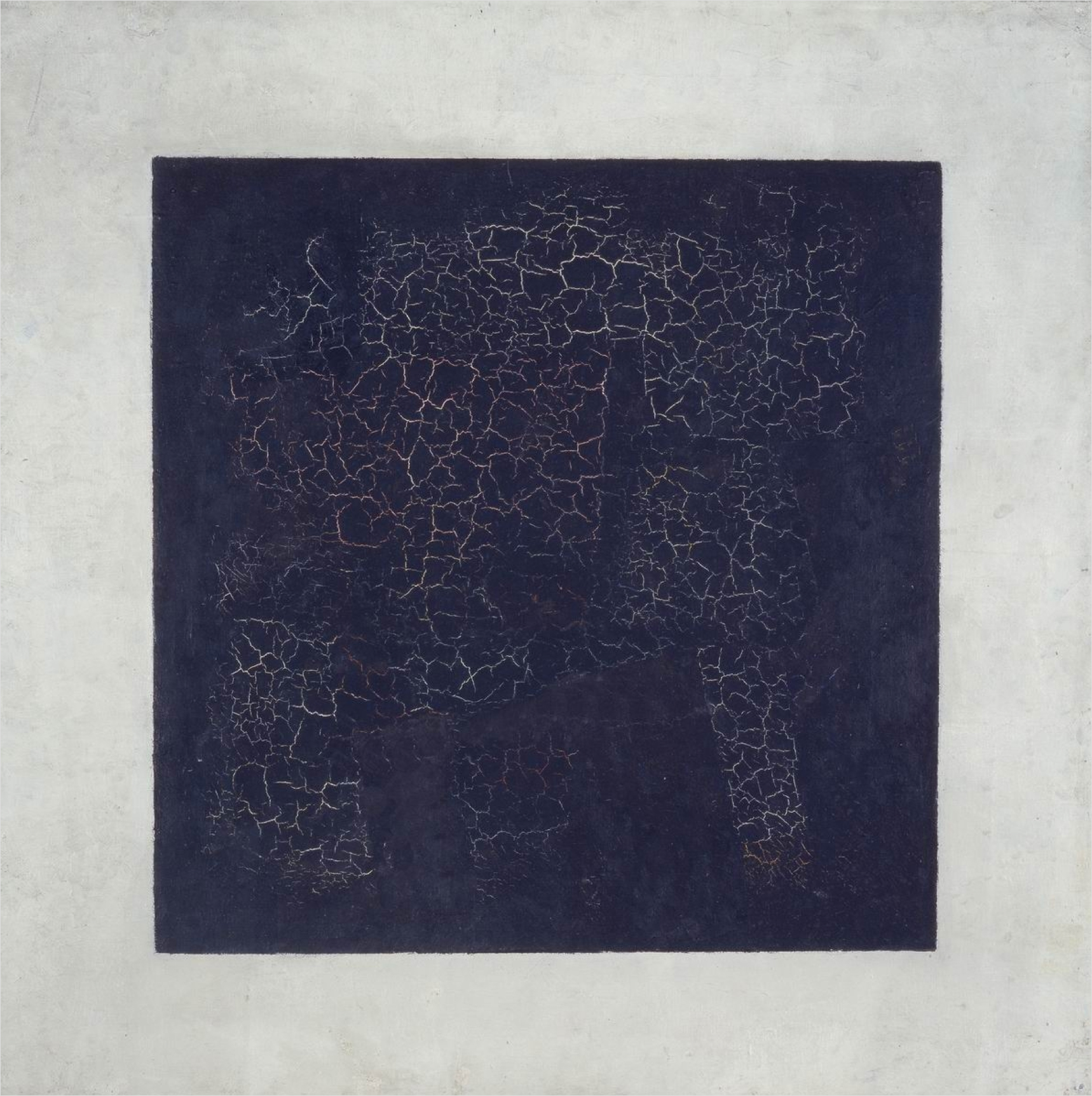

Who created the first work of abstract art has long been a fraught question indeed. Better, perhaps, to ask who first said of a work of art that a kid could have made it. A strong contender in that division is the Russian artist Véra Pestel, whom history remembers as having reacted to Kazimir Malevich’s 1915 painting Black Square with the words “Anyone can do this! Even a child can do this!” Yes, writes novelist Tatyana Tolstaya a century later in the New Yorker, “any child could have performed this simple task, although perhaps children lack the patience to fill such a large section with the same color.” And in any case, time having taken its toll, Malevich’s square doesn’t look quite as black as it used to.

Nor was the square ever quite so square as we imagine it. “Its sides aren’t parallel or equal in length, and the shape isn’t quite centered on the canvas,” says the narrator of the animated TED-Ed lesson above. Instead, Malevich placed the form slightly off-kilter, giving it the appearance of movement, and the white surrounding it a living, vibrating quality.”

Fair enough, but is it art? If you’d asked Malevich himself, he might have said it surpassed art. In 1913, he “realized that even the most cutting-edge artists were still just painting objects from everyday life, but he was irresistibly drawn to what he called ‘the desert,’ where nothing is real except feeling.” Hence his invention of the style known as Suprematism, “a departure from the world of objects so extreme, it went beyond abstraction.”

Malevich made bold claims for Suprematism in general and Black Square in particular. “Up until now there were no attempts at painting as such, without any attribute of real life,” he wrote. “Painting was the aesthetic side of a thing, but never was original and an end in itself.” As Tolstaya puts it, he “once and for all drew an uncrossable line that demarcated the chasm between old art and new art, between a man and his shadow, between a rose and a casket, between life and death, between God and the Devil. In his own words, he reduced everything to the ‘zero of form.’ ” She calls this zero’s emergence in such a stark form “one of the most frightening events in art in all of its history of existence.” If so, here we have an argument for not letting young children see Black Square and enduring the consequent nightmares — even if they could have painted it themselves.

Related content:

Steve Martin on How to Look at Abstract Art

An Interactive Social Network of Abstract Artists: Kandinsky, Picasso, Brancusi & Many More

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities, the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.

Anyone interested it Malevich’s art and the other wonderful artists of this period may find this website interesting: http://artofthezero.com/

There’s also a film about the recent discovery of work from the movement. Here’s a link: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=d9q22pQ5hdc