Odds are you’re acquainted with the lady pictured above.

She’s called La Catrina, and her likeness adorns countless t‑shirts and tote bags.

She is a popular Halloween costume and a mainstay of Day of the Dead celebrations.

She pops up in the animated family feature, Coco, to guide its young hero to the Land of the Dead.

She’s spent the better part of a century making cameos in numerous artists works, most famously Diego Rivera’s surreal 1947 mural, Sueño de una Tarde Dominical en la Alameda Central, a fever dream that places her front and center, arm in arm with a distinguished-looking, mustachioed gent in a bowler hat.

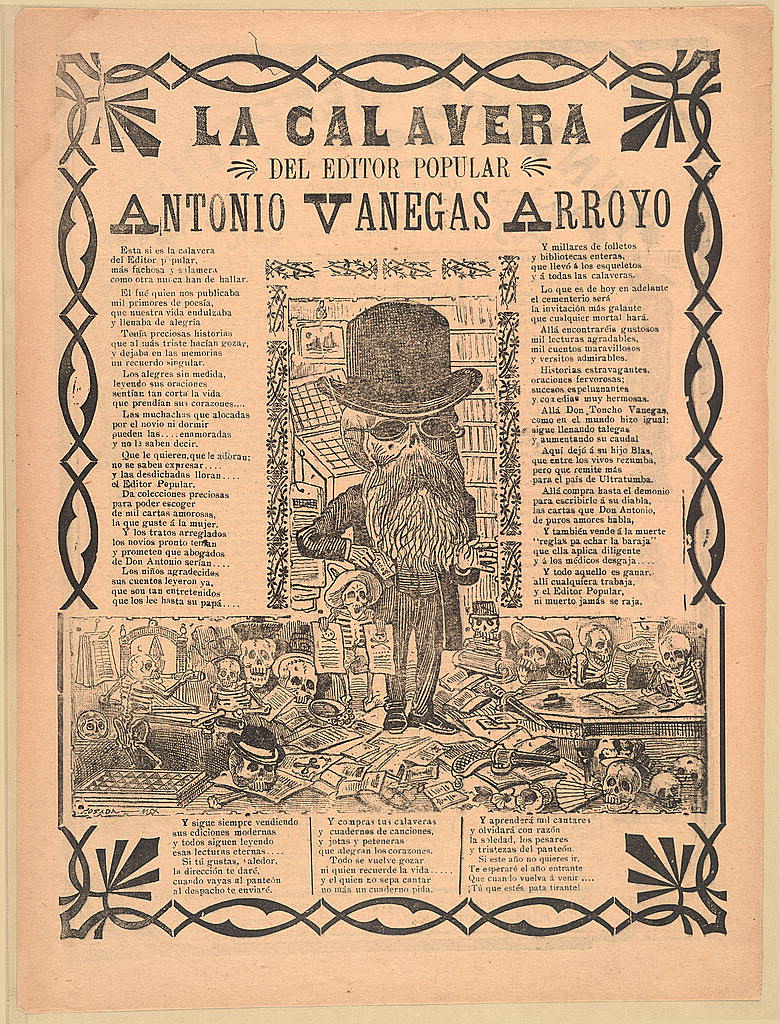

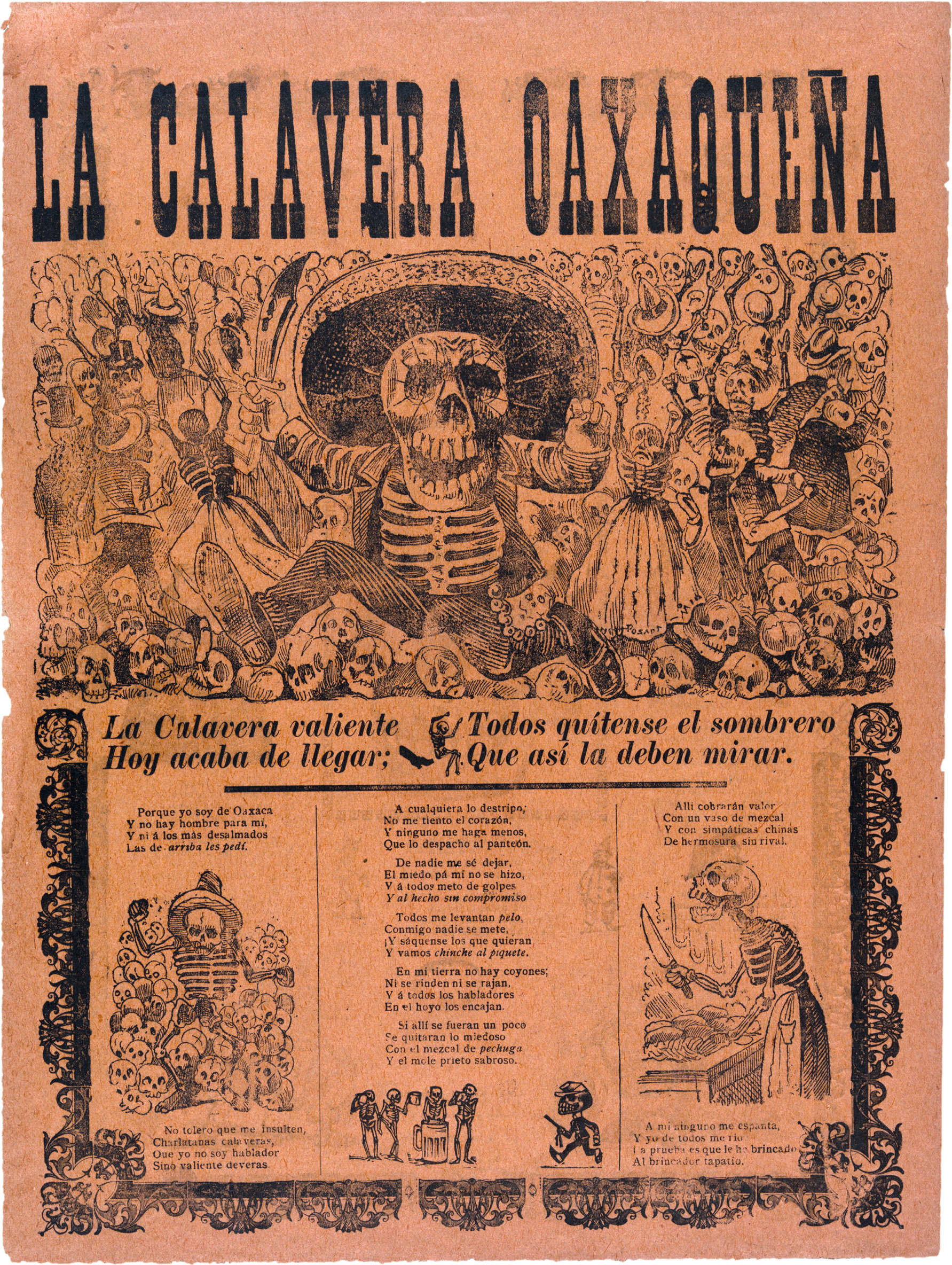

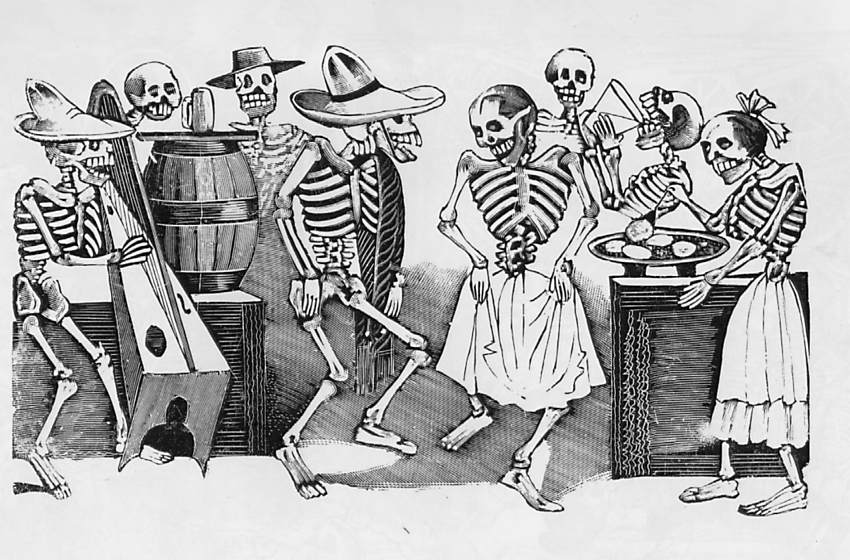

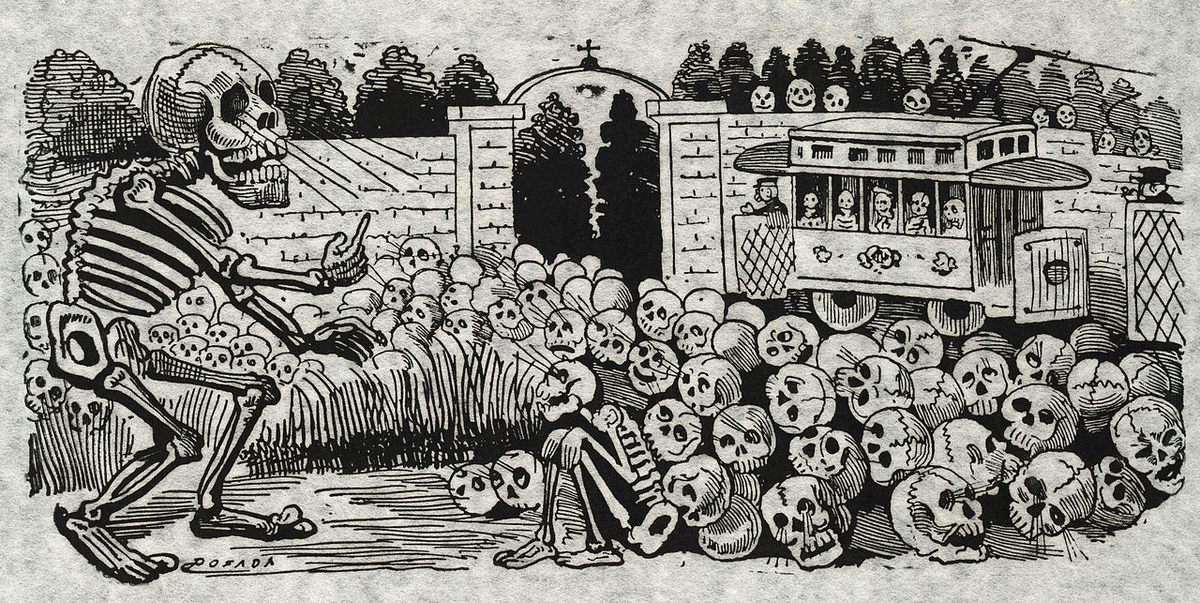

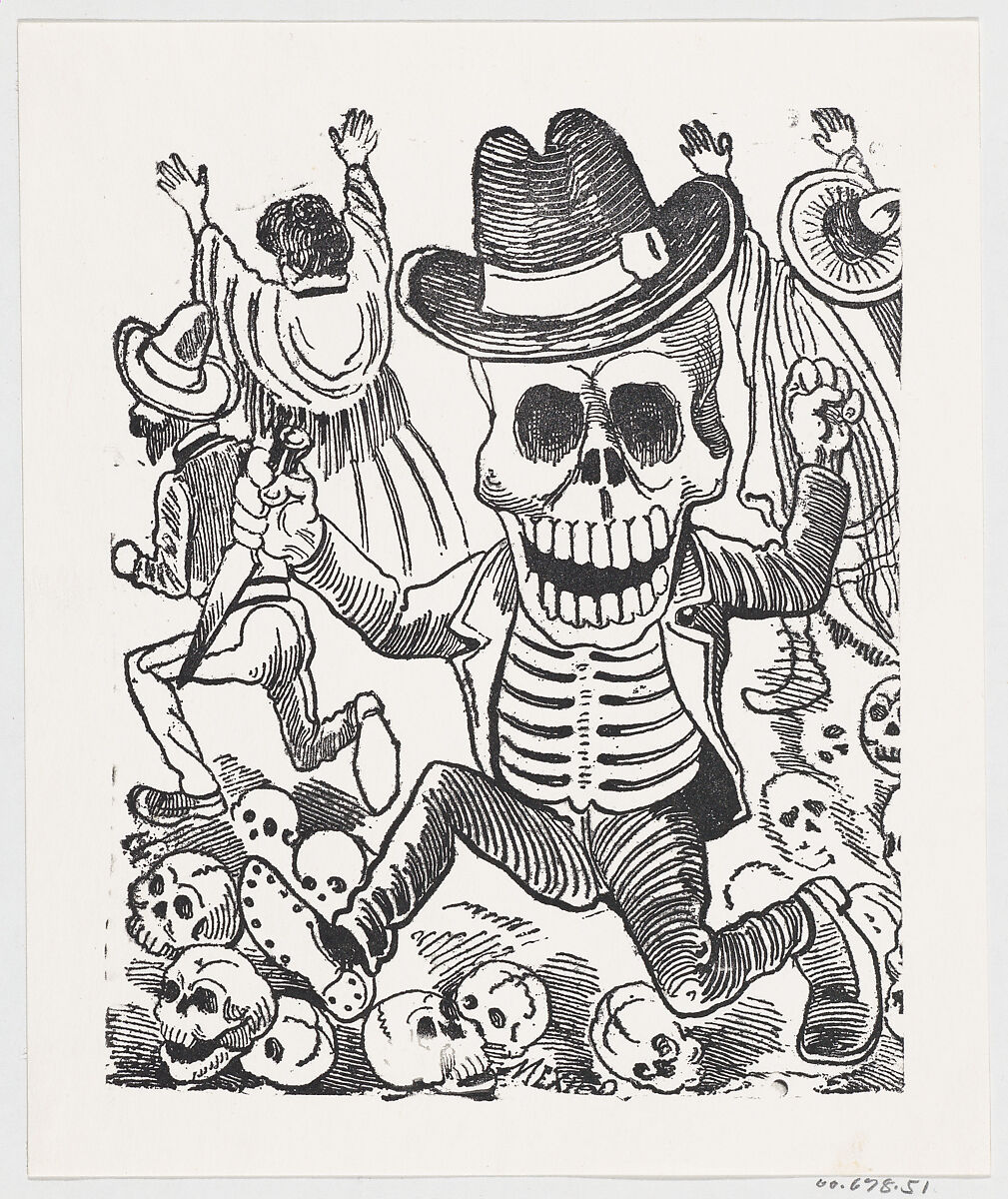

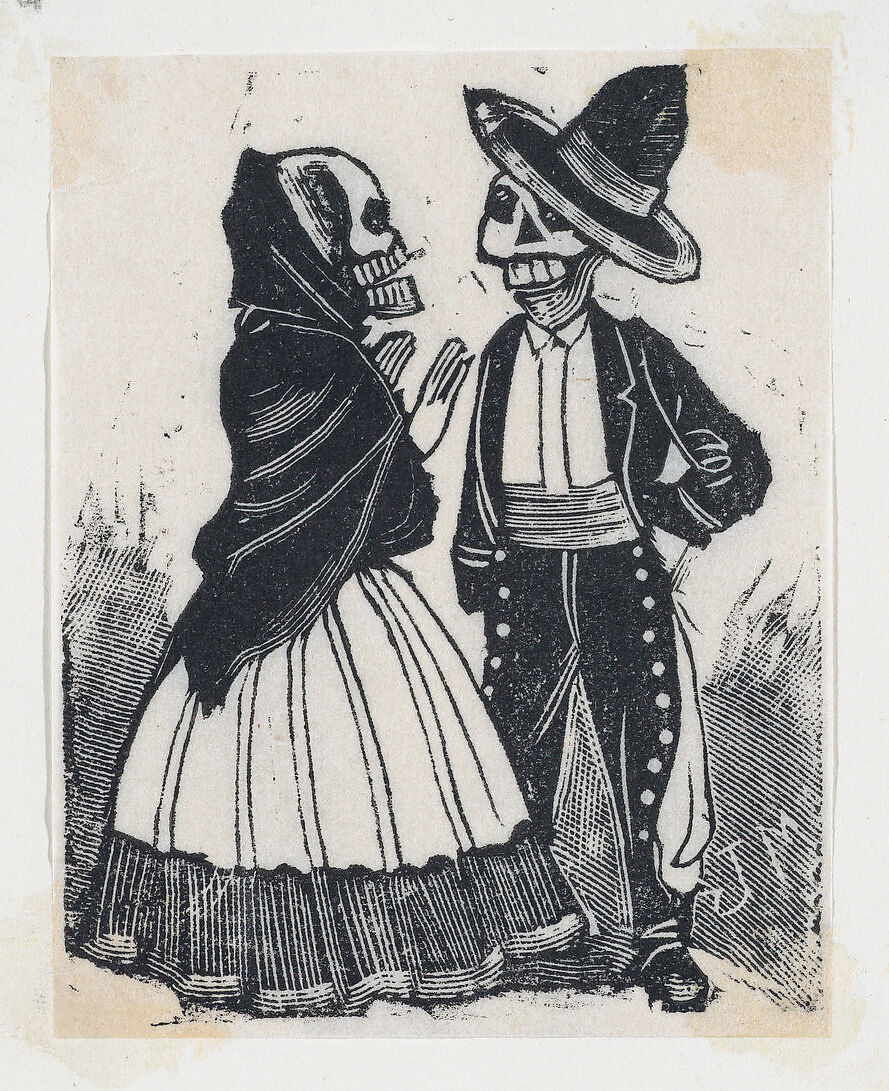

That gent is her original creator, José Guadalupe Posada, a hardworking printmaker and political cartoonist who produced over 20,000 images during his lifetime, on subjects ranging from the Mexican Revolution and other events, both current and historical, to popular entertainment and the daily lives of average men and women.

The artist frequently hammered his point home by depicting the parties in his works as calaveras - exuberant skeletons seemingly unaware they had lost all flesh and blood.

Posada was still a teenager in 1871 when a hometown paper picked up his first cartoons. One reportedly enraged a local politician to such a degree that the paper was forced to cease publication.

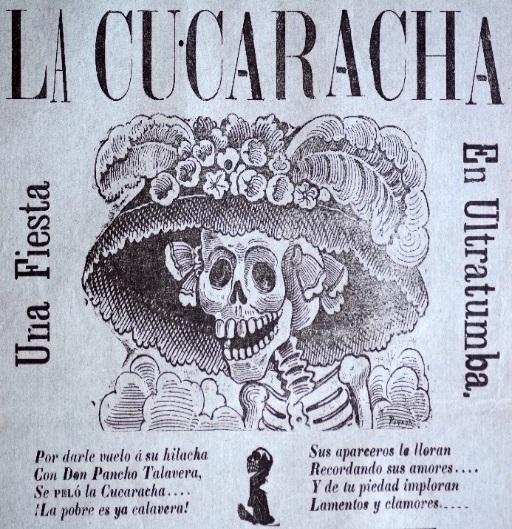

La Catrina was published posthumously in 1913, as a broadsheet illustration accompanying a satirical poem about chickpea vendors. It’s believed that Posada intended his image to be a jab at upper class Mexican women obsessed with European fashions.

(Rivera was the one who changed her name from La Cucaracha — the cockroach — to the much more lyrical La Catrina. He also planted the seed that Posada, who died penniless and largely forgotten, had been a revolutionary. The Mexican progressive printmaking collective El Taller Grafica Popular took graphic inspiration from his calaveras, while embracing and disseminating this myth.

What’s that they say about imitation being the sincerest form of flattery?

After Posada’s death, his colleagues at the publishing firm of Antonio Vanegas Arroyor, saved time and money by continuing to produce work from his blocks and plates.

As Jim Nikas, founding director of the Posada Art Foundation told Atlas Obscura “If the image was neutral enough, you could change the text and use it as an illustration for any story.”

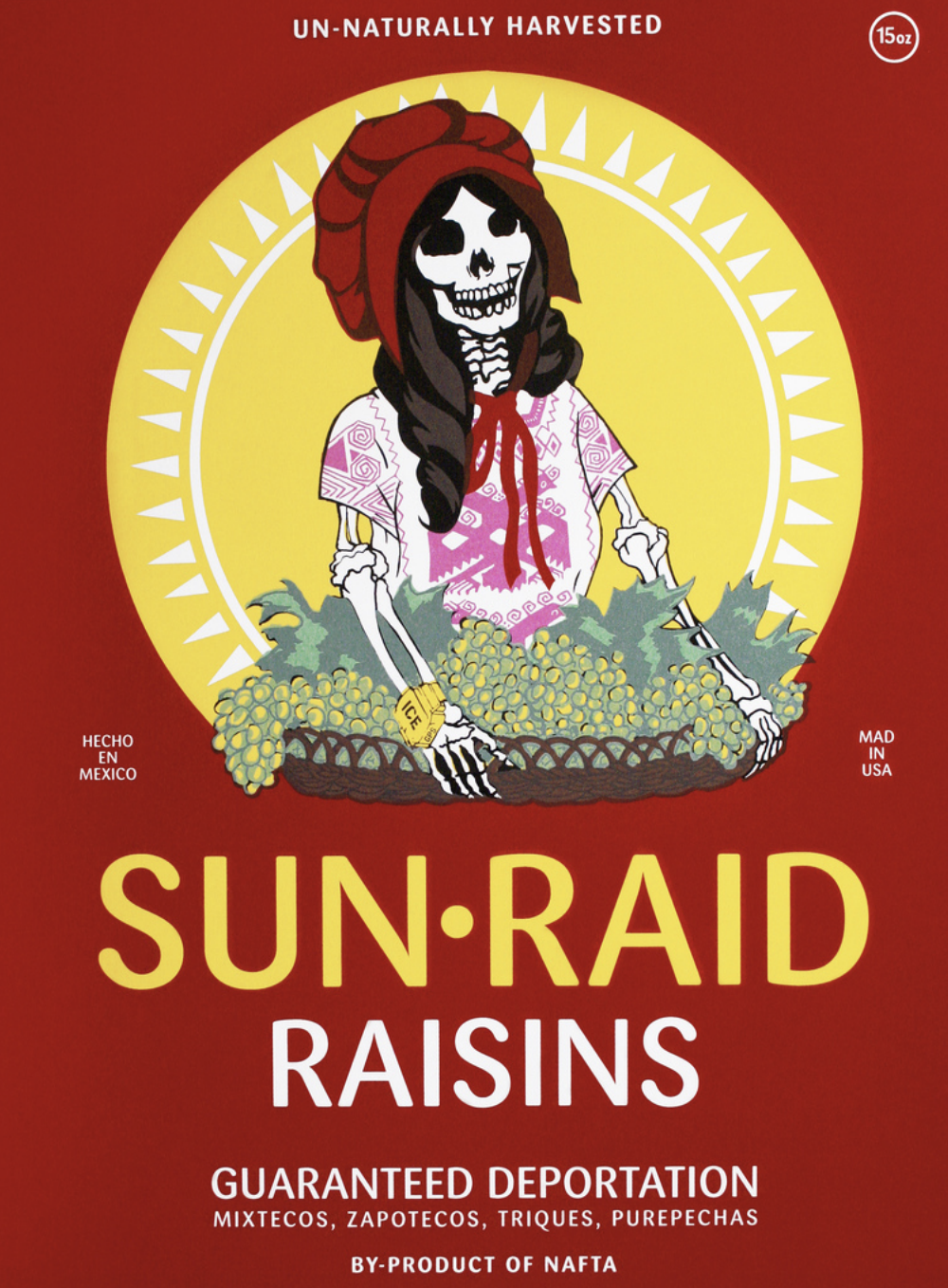

Whether increasing public awareness of harmful agricultural pesticides, protesting American immigration policies, or, uh, selling tequila, 21st century artists, activists, and entrepreneurs continue to harness Posada’s vision for their own purposes.

Nikas, who sampled Posada’s La Calavera de Don Quixote for an Occupy Wall Street collaboration with Art Hazelwood and Marsha Shaw writes that “the calavera is something we all have biologically in common and, accordingly, may be used to convey messages:

Posada and his publishers used depictions of calaveras not only to remind us of our collective mortality but also to shed light. His illustrations were often satirical caricatures uprooted from the current political climate and used to poke fun at our human condition. This use was evolutionary, occurring over time, and as applicable today as it was over a century ago.

See more of José Guadalupe Posada’s calaveras in the Library of Congress’ Prints and Photographs Division collection.

– Ayun Halliday is the Chief Primatologist of the East Village Inky zine and author, most recently, of Creative, Not Famous: The Small Potato Manifesto and Creative, Not Famous Activity Book. Follow her @AyunHalliday.

Leave a Reply