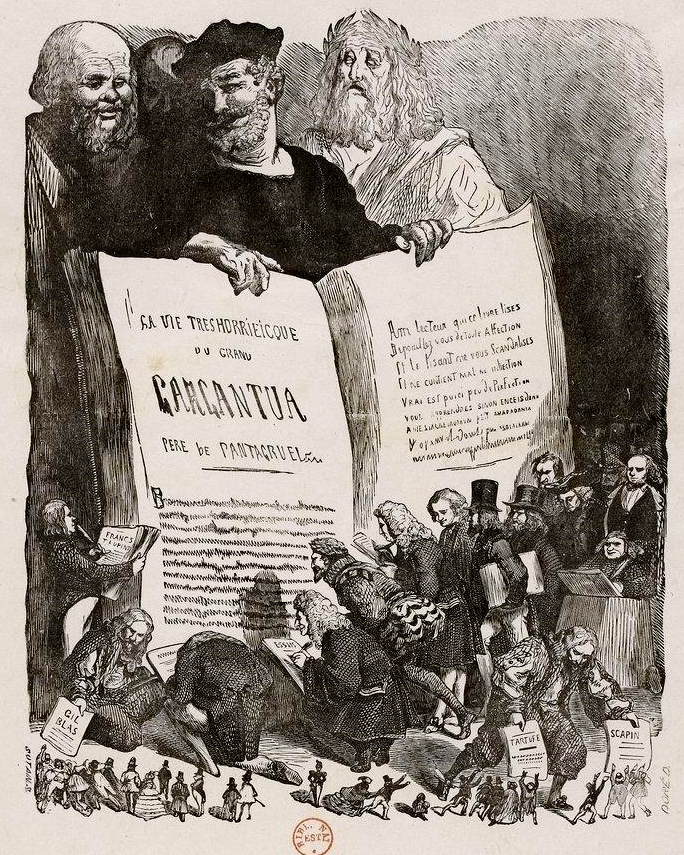

When François Rabelais came up with a couple of giants to put at the center of a series of inventive and ribald works of satirical fiction, he named one of them Gargantua. That may not sound particularly clever today, gargantuan being a fairly common adjective to describe anything quite large. But we actually owe the word itself to Rabelais, or more specifically, to the nearly half-millennium-long legacy of the character into whom he breathed life. But there’s so much more to Les Cinq livres des faits et dits de Gargantua et Pantagruel, or The Five Books of the Lives and Deeds of Gargantua and Pantagruel, whose enduring status as a masterpiece of the grotesque owes much to its author’s wit, linguistic virtuosity, and sheer brazenness.

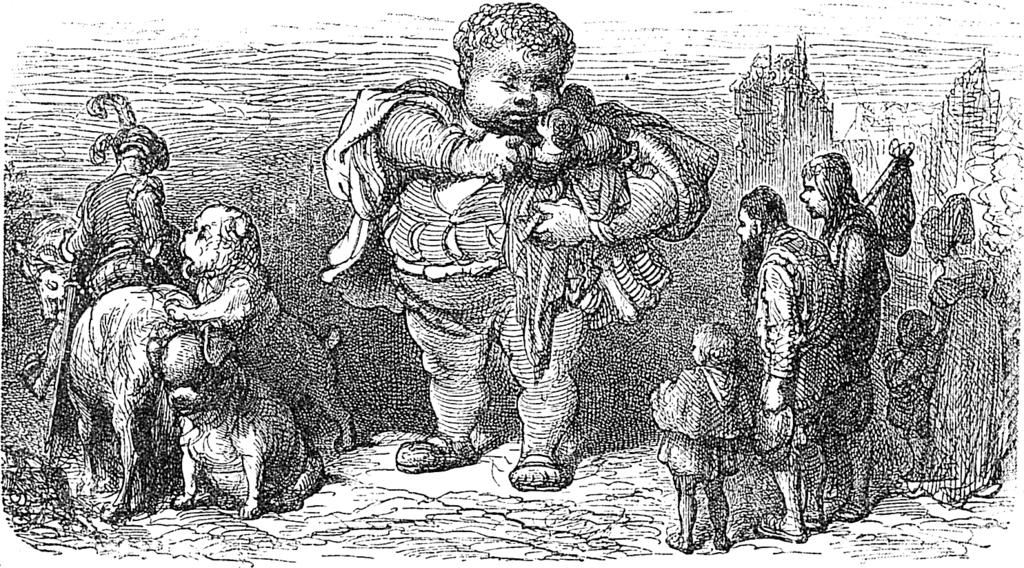

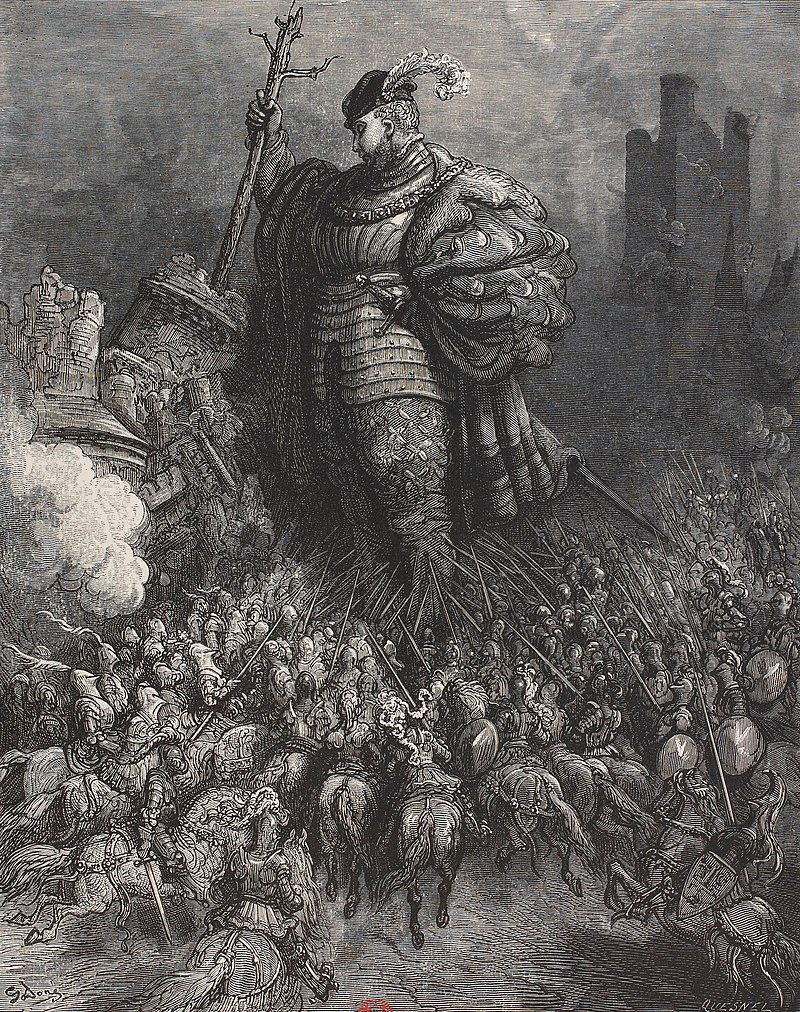

Nor has it hurt that the books have inspired vivid illustrations from a host of artists, one of whom in particular stands out: Gustave Doré, whom Richard Smyth calls “one of the most prolific — and most successful — book illustrators of the nineteenth century.”

Here at Open Culture, we’ve previously featured the art he created to accompany the work of Dante, Cervantes, and Poe, each a writer possessed of a highly distinctive set of literary powers, and each of whom thus received a different but equally lavish and evocative treatment from Doré.

For Rabelais, says the site of book dealer Heribert Tenschert, the 22-year-old artist produced (in 1854) “100 images that oscillate between the whimsical and the uncanny, between realism and fantasy,” a count he would expand to 700 in another edition two decades later.

You can see a great many of Doré’s illustrations for Gargantua and Pantagruel at Wikimedia Commons. The simultaneous extravagance and repugnance of the series’ medieval France may seem impossibly distant to us, but it can hardly have felt like yesterday to Doré either, given that he was working three centuries after Rabelais.

As suggested by Heribert Tenschert, perhaps these imaginative visions of the Middle Ages — like Balzac’s Rabelaisian Les contes drolatiques, which he also illustrated — “resonated with Doré because they reminded him of the mysterious atmosphere of his childhood, which he had spent in the middle of the medieval city of Strasbourg.” Whatever his connection, Doré created images that still bring to mind a whole range of descriptors: somberly jocular, rigorously voluptuous, compellingly repellent, and above all pantagruelist. (Look it up.)

Related Content:

Gustave Doré’s Exquisite Engravings of Cervantes’ Don Quixote

Gustave Doré’s Dramatic Illustrations of Dante’s Divine Comedy

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities, the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.

Leave a Reply