Today, if you want to get started in home brewing, shop for a synthesizer, find out what cybernetics is, order non-genetically-modified seeds, start your own mushroom farm, learn how to repair a Volkswagen, subscribe to libertarian publications, purchase the work of Marshall McLuhan, sign up for an outdoor excursion, read an essay on zen Buddhism, compare home-birth setups, gather homeschooling materials, build a geodesic dome, you go to one place first: the internet. Half a century ago, when the personal computer had only just come into existence, that wouldn’t have been an option. But provided you were sufficiently tapped into the counterculture, you could open up the nineteen-seventies equivalent of the internet: The Whole Earth Catalog.

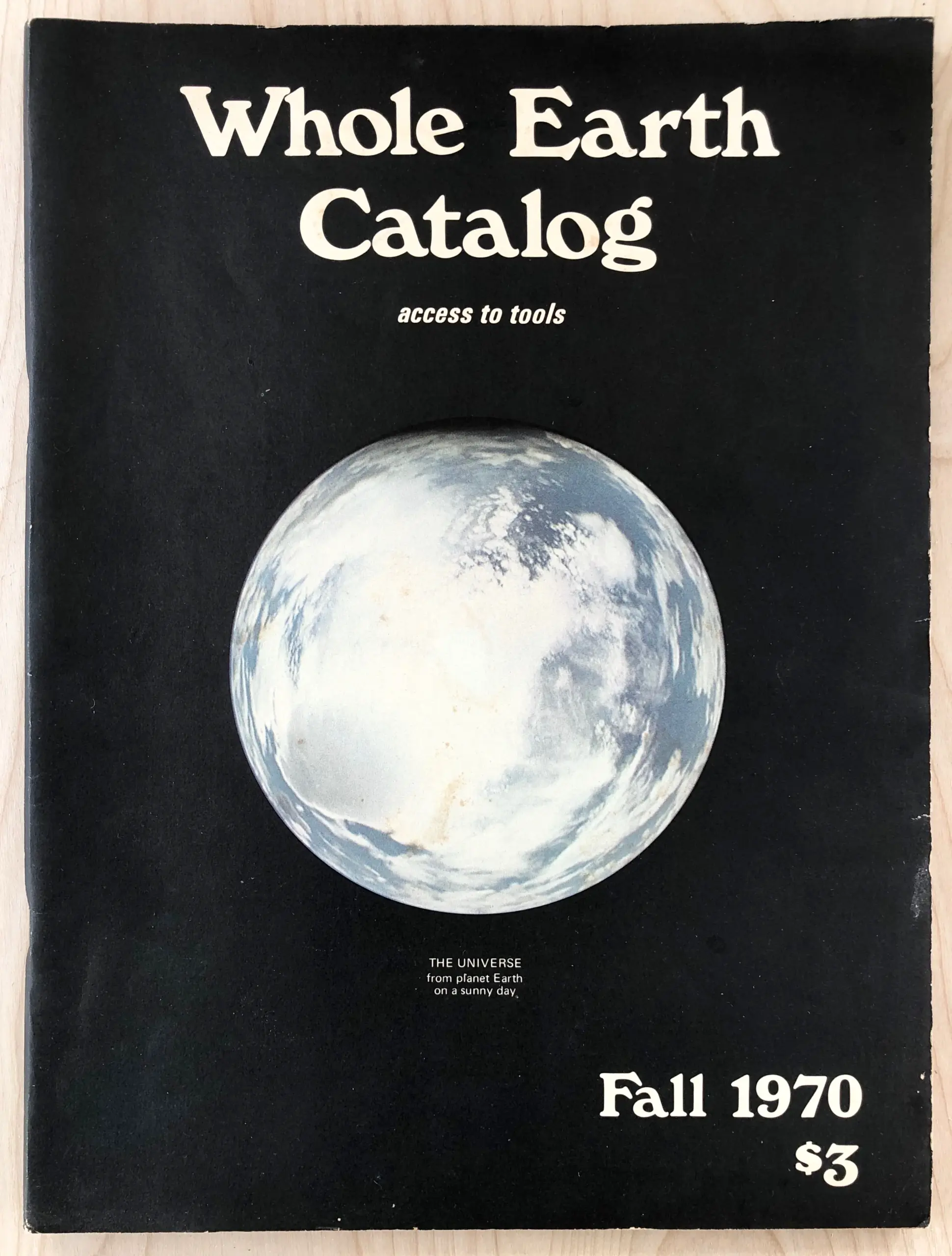

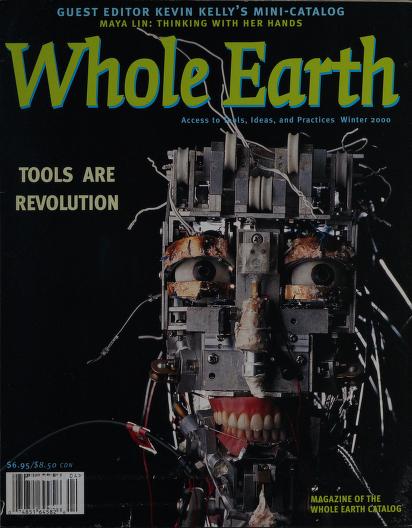

Launched by Stewart Brand in 1968, the Whole Earth Catalog curated and presented the products and services of a wide variety of businesses all between the covers of one increasingly weighty printed volume offering what its slogan called “access to tools.”

While certain of its sections reflected the most literal meaning of the term “tools” — you could’ve kept a pretty robust farm going with all the implements on offer, and no doubt more than a few readers tried to do so — the larger enterprise seemed to run on the goal of expanding the definition of what a tool could be, as well as the range of possibilities it could open to its user. Even subscribers who never bought a product could receive an education from the catalog’s often eccentric but always informative descriptions of those products.

“Behind the information, the advice, the hints, and the facts, this book is about coming to see things as they are, through your own eyes, instead of the hired eyes of some expert or other. It’s about training yourself to trust yourself, and trusting yourself to train yourself, until you‘re able to claim your right as a human to be competent with your hands.” These words come from writer and documentarian Gurney Norman’s capsule review, in the spring 1970 Whole Earth Catalog, of Joan Ranson Shortney’s book, How to Live on Nothing (described therein as “our best-selling book”). But Norman could just as well have been describing the Whole Earth Catalog itself, which was all about the ability of individuals and small groups, equipped with not just technology new and old but also deep reserves of optimism and humor, to determine their own destiny.

“The Whole Earth Catalog offered a vision for a new social order,” writes the New Yorker’s Anna Wiener, “one that eschewed institutions in favor of individual empowerment, achieved through the acquisition of skills and tools. The latter category included agricultural equipment, weaving kits, mechanical devices, books like Kibbutz: Venture in Utopia, and digital technologies and related theoretical texts, such as Norbert Wiener’s Cybernetics and the Hewlett-Packard 9100A, a programmable calculator.” Other sections might offer Gravity’s Rainbow; an Apple II home computer; something called “self-therapeutic rubber”; and even a hot tub. “Many a newcomer to California remembers forever the trauma of first being invited — at a perfectly ordinary party — to strip and enter a steaming tub full of strangers,” writes Brand in the Next Whole Earth Catalog of fall 1980, which may sound a bit late in the game for that sort of thing.

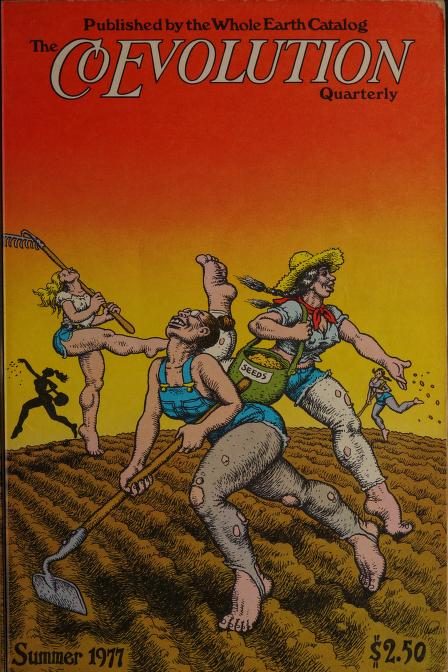

But then, the spirit of the Whole Earth Catalog, first animated by the free-enterprise-and-free-love nineteen-sixties and seventies, has long outlasted its original cultural moment — and indeed the catalog itself, which ceased publication in 1998. But now, thanks to Gray Area and the Internet Archive, you can read and download many issues of not just the Whole Earth Catalog but also its successor publications, from CoEvolution Quarterly to Whole Earth Magazine, in a new online collection spanning the years 1970 to 2002. To browse it is to enter a countercultural time machine, experiencing both the preposterousness and the prescience of the counterculture as if for the first time. But then, for the vast majority of its visitors here in the twenty-first century — who know that counterculture only indirectly, through its wide but diffuse influence on everything up to and including the internet — it will be the first time. Enter the collection here.

Related content:

Watch Stewart Brand’s 6‑Part Series How Buildings Learn, With Music by Brian Eno

Brian Eno Creates a List of 20 Books That Could Rebuild Civilization

Buckminster Fuller Tells the World “Everything He Knows” in a 42-Hour Lecture Series (1975)

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities, the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.

Thank you for sharing this fascinating information about the online archive of The Whole Earth Catalog and its related publications. It’s an exciting resource that provides insight into the counterculture of the past. The collection’s availability allows us to revisit and appreciate the ideas and tools that shaped a particular era and continue to influence our world today.

avukat

This would be a great resource if we could OCR the text into something legible for screen readers. With the column structure of the text, OCR attempts with the PDFs just are a jumble making this beautiful resource inaccessible to many.

HAD the personal computer come into existence 50 years ago. I’m 68 years old and I cannot remember anybody using a desktop or home computer at that time. Mind, they were beginning to be very popular FORTY years ago…

I had forgotten about the Whole Earth Catalog, but your article brought back a flood of memories. I spent many happy hours pouring over the first edition when it came out.

Olivetti Programma 101, 1965: https://www.pingdom.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/08/programma101-uk.jpg

I grew up in the late 50’s — 60’s and once discovered, the Whole Earth Catalog led my parents into espousing some crazy ideas, like raising chickens, making granola and yogurt, baking bread, maintaining a compost pile, and even our epic family project of building a DIY fallout shelter. We had an interesting childhood, for sure.

It’s great to see that the contents have been archived and available online. Where can I find a searchable database of the WEC?

Thank you!