Katsushika Hokusai created his best-known woodblock print The Great Wave Off Kanagawa — or rather he finished its definitive version — when he was in his early sixties. That may sound somewhat late in the day by the standards of visual artists, but as Hokusai himself saw it, he was just getting started. At the Public Domain Review, Koto Sadamura quotes the artist’s own words, as included in the book One Hundred Views of Mt. Fuji: “Until the age of seventy, nothing I drew was worthy of notice. At seventy-three years, I was somewhat able to fathom the growth of plants and trees, and the structure of birds, animals, insects and fish.”

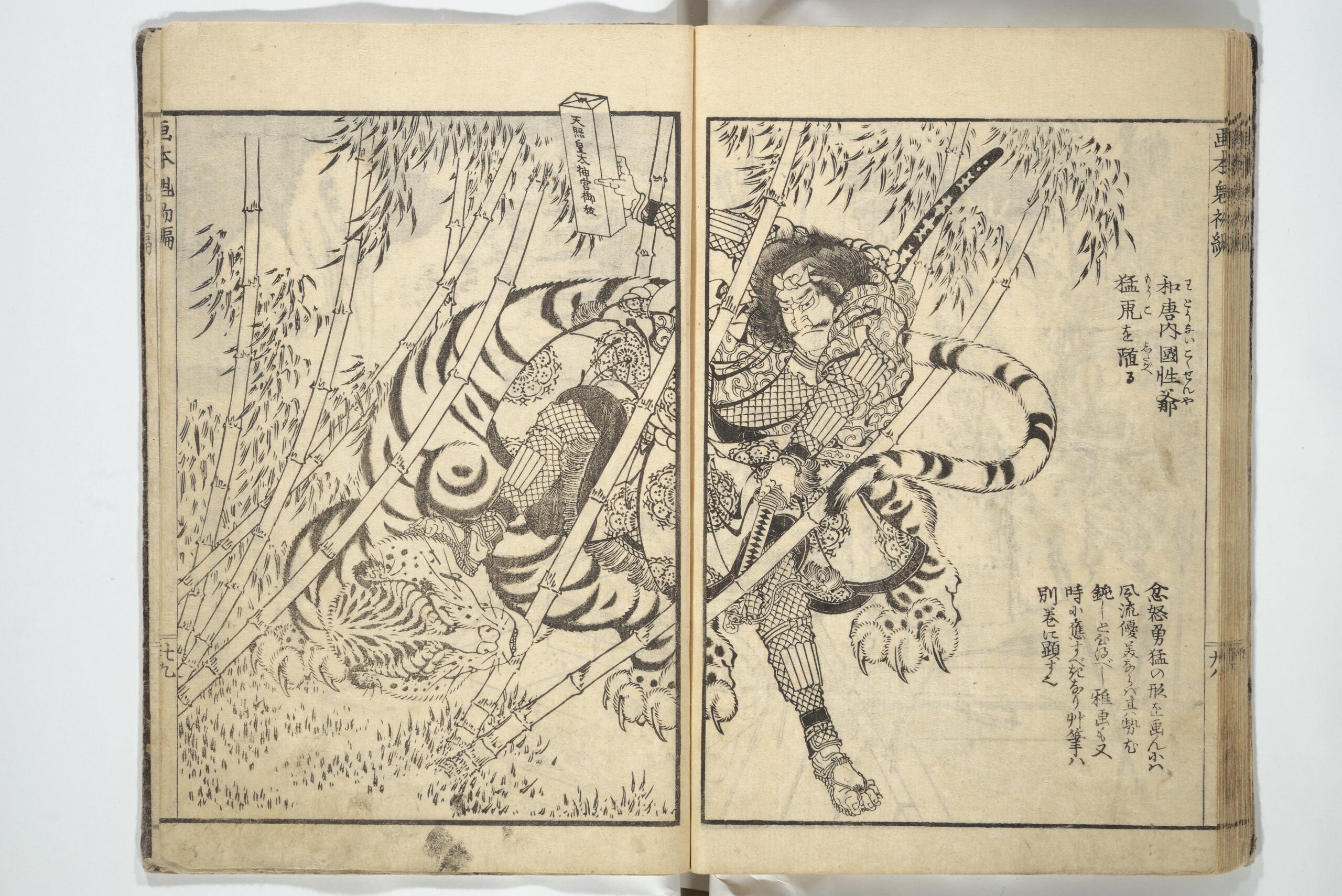

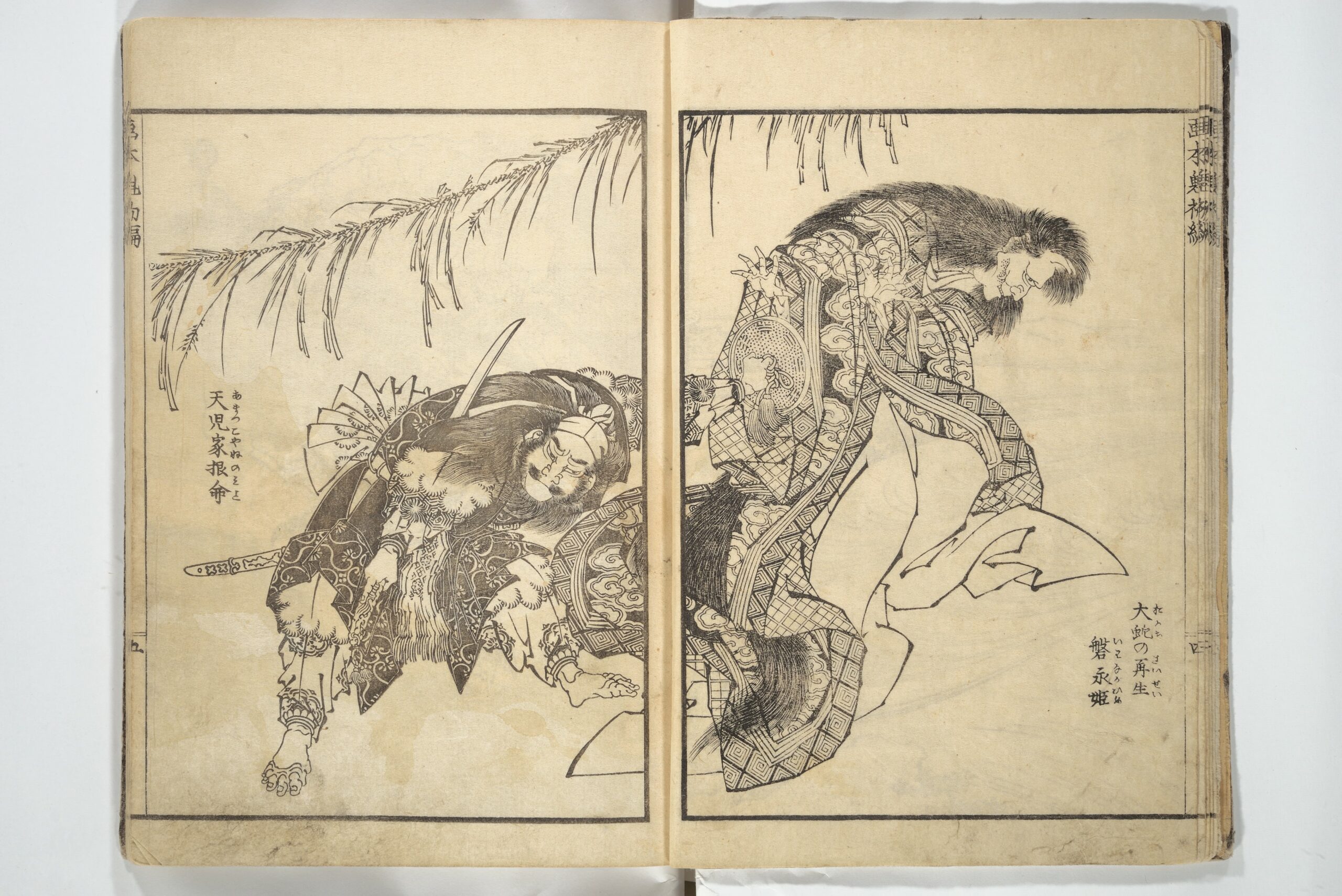

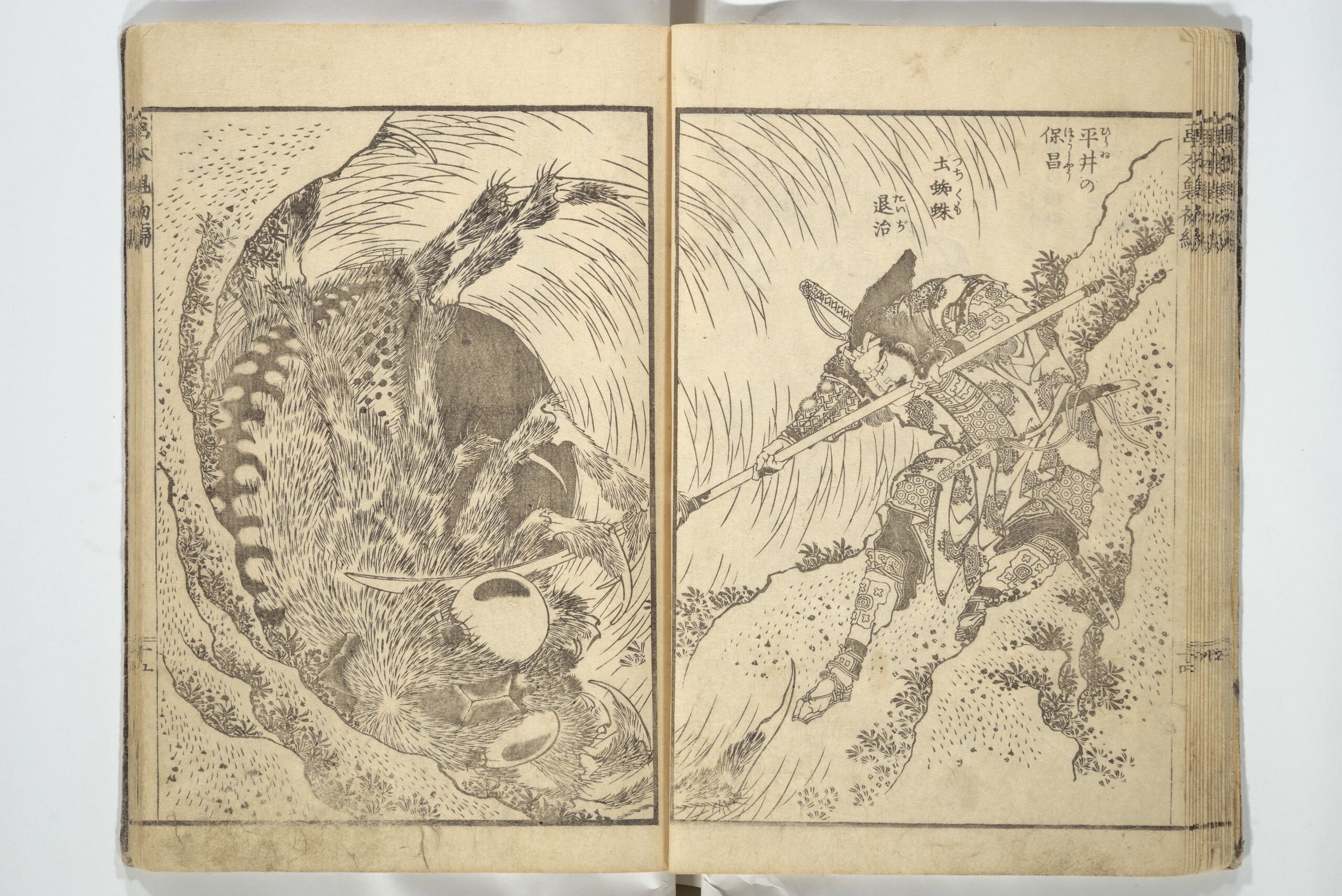

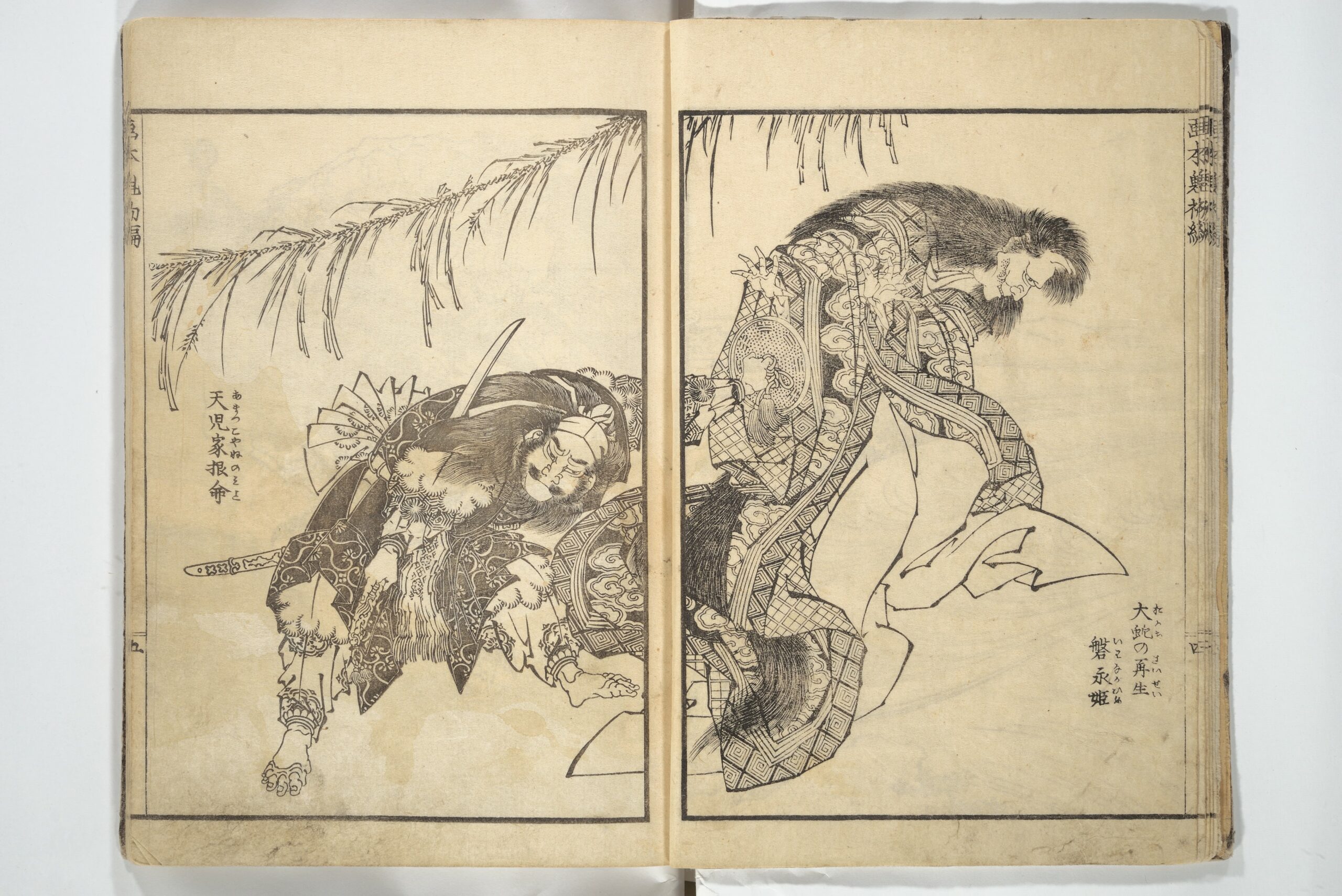

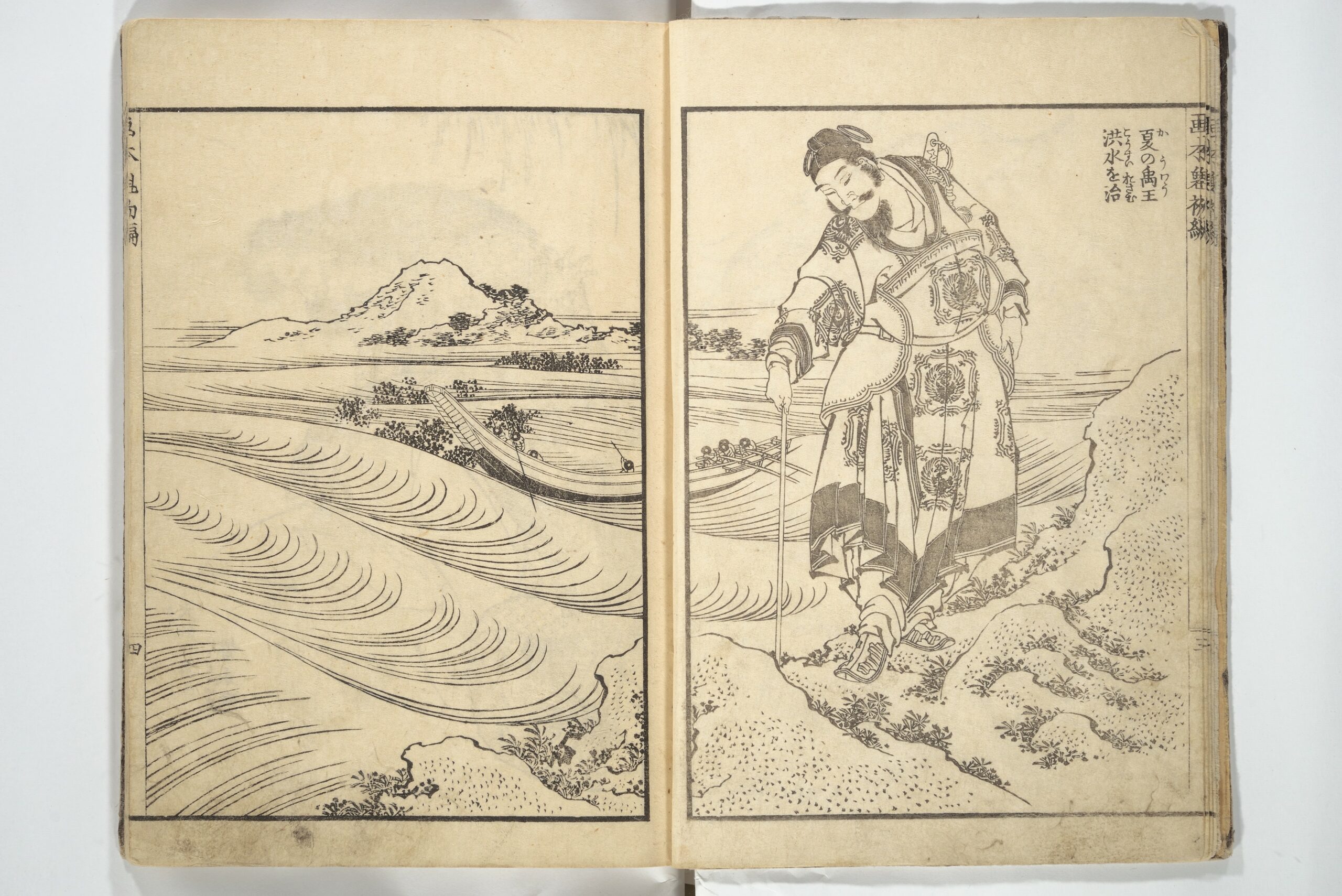

Sadamura goes on to introduce a different, lesser-known, and even later series of Hokusai’s artworks: “Wakan ehon sakigake, which assembles images of famous Japanese and Chinese warriors, both historical and legendary. The Japanese term sakigake in the title signifies outstanding figures or leaders (Wakan means Japanese and Chinese, and ehon is a picture book).”

Like many a hardworking ukiyo‑e artist, Hokusai created these images to order, his publisher having asked him to “fill three volumes with ‘wisdom’ [chi], ‘humanity’ [jin] and ‘bravery’ [yū], using examples of widely celebrated mighty heroes as reminders of military arts even in times of peace.”

The results, which you can see both at the Public Domain Review and the site of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, clearly fulfill their mandate of revivifying from a glorious past, real or imagined. But they also exude a certain aesthetic familiarity even today: in Hokusai’s depiction of the Heian-period warrior Hirai Yasumasa “subduing a monster spider,” for example, “lines in the background trace the motion of the gigantic arachnid as it tumbles and its sickle-like legs flail in the air, emphasizing the movement and force in a way that resonates with the visual effects of modern manga.”

All the more surprising, then, not just that the Wakan ehon sakigake (or at least two of its planned three volumes) are now 187 years old, but also that Hokusai himself was seventy-six at the time. “Each tiny leaf growing on the rocks and each textural mark on the ragged surface is animated, filling the picture with vibrating energy,” Sadamura writes. “Every single strand of hair is charged with life.”

But the master foresaw greater achievements ahead, only after attaining the experience that would attend an even more advanced age: “At one hundred and ten, every dot and every stroke will be as though alive.” Alas, Hokusai died in 1849, at the tender age of 88, leaving us to imagine the level of artistry he might have attained had he reached maturity.

Related content:

View 103 Discovered Drawings by Famed Japanese Woodcut Artist Katsushika Hokusai

Hand-Colored 1860s Photographs Reveal the Last Days of Samurai Japan

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities, the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.

Leave a Reply