A funny thing happened on the way to the 15th century…

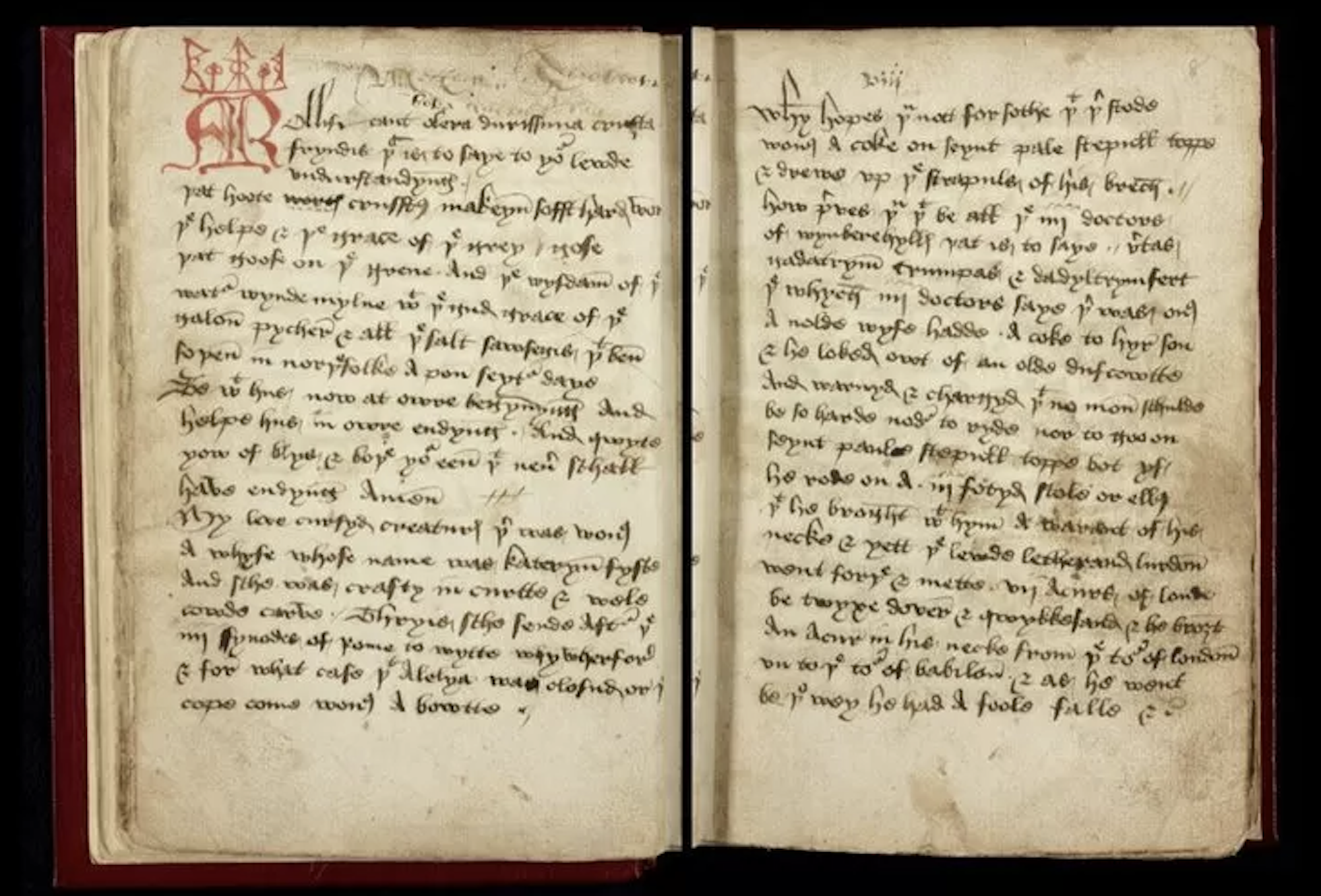

Dr. James Wade, a specialist in early English literature at the University of Cambridge, was doing research at the National Library of Scotland when he noticed something extraordinary about the first of the nine miscellaneous booklets comprising the Heege Manuscript.

Most surviving medieval manuscripts are the stuff of high art. The first part of the Heege Manuscript is funny.

The usual tales of romance and heroism, allusions to ancient Rome, lofty poetry and dramatic interludes… even the dashing adventures of Robin Hood are conspicuously absent.

Instead it’s awash with the staples of contemporary stand up comedy — topical observations, humorous oversharing, roasting eminent public figures, razzing the audience, flattering the audience by busting on the denizens of nearby communities, shaggy dog tales, absurdities and non-sequiturs.

Repeated references to passing the cup conjure an open mic type scenario.

The manuscript was created by cleric Richard Heege and entered into the collection of his employers, the wealthy Sherbrooke family.

Other scholars have concentrated on the manuscript’s physical construction, mostly refraining from comment on the nature of its contents.

Dr. Wade suspects that the first booklet is the result of Heege having paid close attention to an anonymous traveling minstrel’s performance, perhaps going so far as to consult the performer’s own notes.

Heege quipped that he was the author owing to the fact that he “was at that feast and did not have a drink” — meaning he was the only one sober enough to retain the minstrel’s jokes and inventive plotlines.

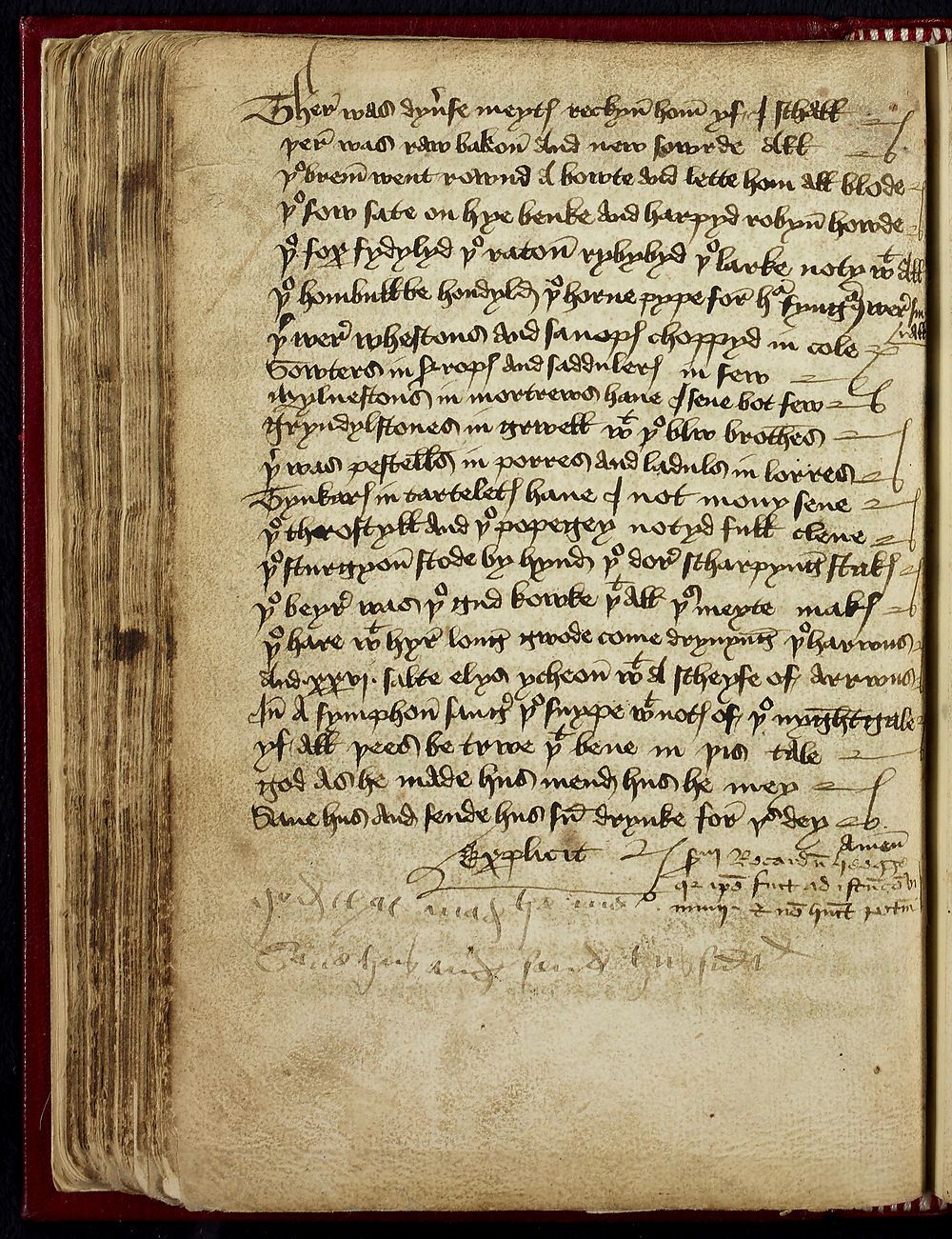

Dr. Wade describes how the comic portion of the Heege Manuscript is broken down into three parts, the first of which is sure to gratify fans of Monty Python and the Holy Grail:

…it’s a narrative account of a bunch of peasants who try to hunt a hare, and it all ends disastrously, where they beat each other up and the wives have to come with wheelbarrows and hold them home.

That hare turns out to be one fierce bad rabbit, so much so that the tale’s proletarian hero, the prosaically named Jack Wade, worries she could rip out his throat.

Dr. Wade learned that Sir Walter Scott, author of Ivanhoe, was aware of The Hunting of the Hare, viewing it as a sturdy spoof of high minded romance, “studiously filled with grotesque, absurd, and extravagant characters.”

The killer bunny yarn is followed by a mock sermon - If thou have a great black bowl in thy hand and it be full of good ale and thou leave anything therein, thou puttest thy soul into greater pain — and a nonsense poem about a feast where everyone gets hammered and chaos ensues.

Crowd-pleasing material in 1480.

With a few 21st-century tweaks, an enterprising young comedian might wring laughs from it yet.

(Paging Tyler Gunther, of Greedy Peasant fame…)

As to the true author of these routines, Dr. Wade speculates that he may have been a “professional traveling minstrel or a local amateur performer.” Possibly even both:

A ‘professional’ minstrel might have a day job and go gigging at night, and so be, in a sense, semi-professional, just as a ‘travelling’ minstrel may well be also ‘local’, working a beat of nearby villages and generally known in the area. On balance, the texts in this booklet suggest a minstrel of this variety: someone whose material includes several local place-names, but also whose material is made to travel, with the lack of determinacy designed to comically engage audiences regardless of specific locale.

Learn more about the Heege Manuscript in Dr. Wade’s article, Entertainments from a Medieval Minstrel’s Repertoire Book in The Review of English Studies.

Leaf through a digital facsimile of the Heege Manuscript here.

Related Content

A List of 1,065 Medieval Dog Names: Nosewise, Garlik, Havegoodday & More

Why Knights Fought Snails in Illuminated Medieval Manuscripts

– Ayun Halliday is the Chief Primatologist of the East Village Inky zine and author, most recently, of Creative, Not Famous: The Small Potato Manifesto and Creative, Not Famous Activity Book. Follow her @AyunHalliday.

” If thou have a great black bowl in thy hand and it be full of good ale and thou leave anything therein, thou puttest thy soul into greater pain”

If this be transcribed correctly, it shows the difference between the subjunctive used after ‘thou’ (have/leave) and the indicative (puttest). The subjunctive is used because ‘If..’ sets up a possibility, rather than a fact.

In modern English the subjunctive is almost extinct, except in a couple of set phrases (e.g. ‘if I were you.…’).

“..And the Lord did grin, and the people did feast upon the lambs and sloths and carp and anchovies and orangutans and breakfast cereals and fruit bats and large chu–”