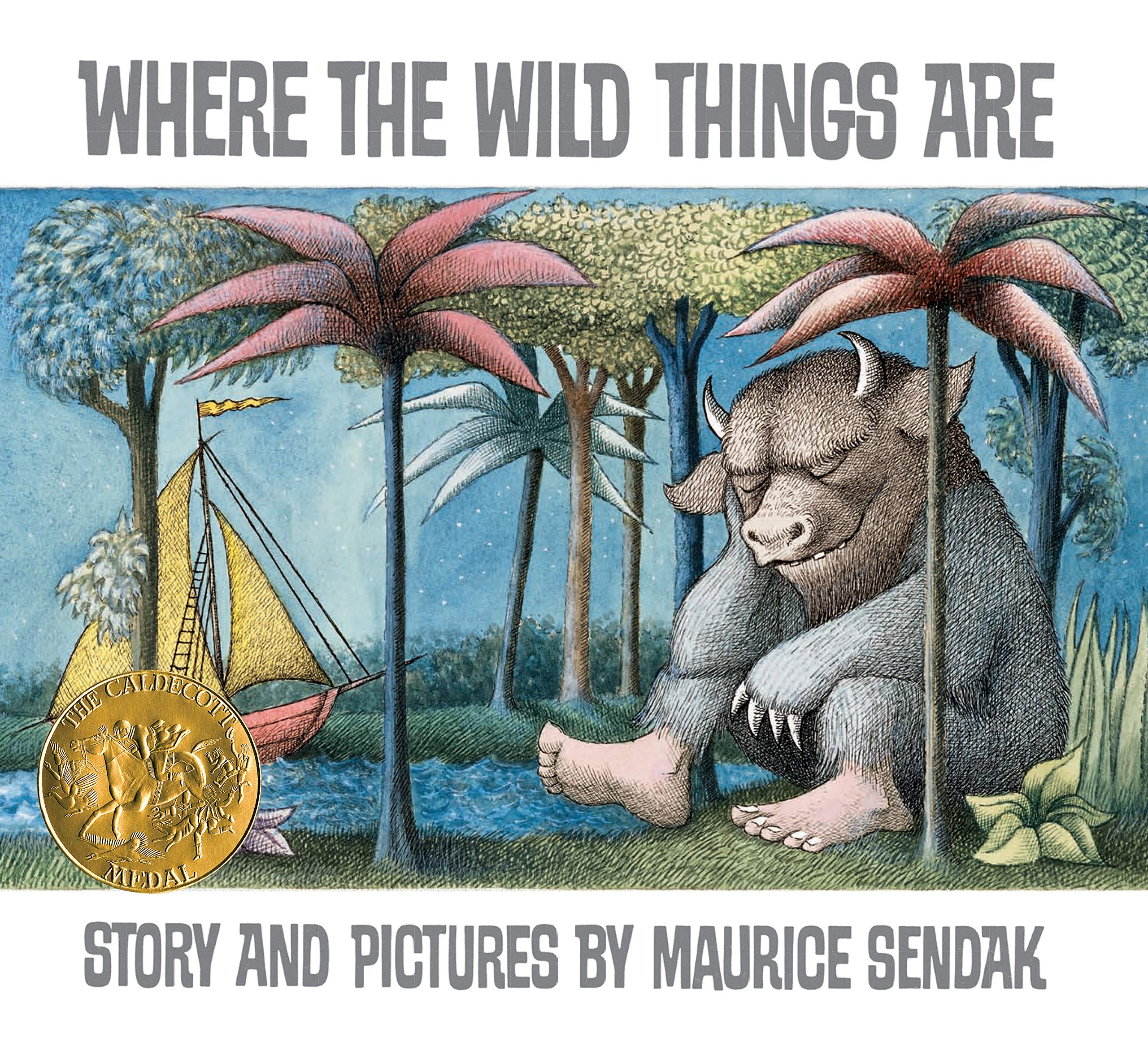

Given the size and demographic profile of J. R. R. Tolkien’s fan base today, it’s easy to forget that he originally wrote The Hobbit for children. For generations of young readers, that novel has stood as the gateway into Tolkien’s much more complex and ambitious Lord of the Rings trilogy — also written for children, at least according to the new poll of 177 experts around the world conducted by the BBC to determine the 100 greatest children’s books of all time. In its results, The Lord of the Rings comes in around the middle, but The Hobbit takes fifth place, behind only the near-universally beloved titles The Little Prince, Pippi Longstocking, Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, and — at number one — Where the Wild Things Are.

Any reader who was a child in the past sixty years will know all of those books; any reader alive will know most of them. Throughout this top-100 list appear classics that have been in the children’s canon longer than any of us have been alive, like Anne of Green Gables, Treasure Island, and Little Women.

A great many works, from Goodnight Moon and The Cat in the Hat to A Wrinkle in Time and From the Mixed-Up Files of Mrs Basil E. Frankweiler — joined it in the middle of the twentieth century. “Books published between the 1950s and 1970s were most prevalent,” says the BBC’s accompanying notes, “which may be related to the age profile of voters, the majority of whom were born in the 1970s and 1980s.”

Indeed, a glance through these results can hardly fail to bring back any of the earliest reading memories of any Generation Xer or millennial. Witness the prevalence of books by Roald Dahl: Charlie and the Chocolate Factory, The BFG, The Witches, Matilda. Even Danny, the Champion of the World, which I remember as relatively lackluster, just makes the cut. Of course, “the furor over the rewriting of Roald Dahl’s novels for modern sensibilities” has lately brought his work back into public discourse; that and other unrelated controversies over what books ought to be made available in school libraries have given us reason to consider once again what children’s literature is, or what it could and should be — a range of questions that kids themselves seem rather better equipped to address than many grown-ups. See the BBC’s complete list here.

Related content:

Discover J. R. R. Tolkien’s Little-Known and Hand-Illustrated Children’s Book Mr. Bliss

Hayao Miyazaki Selects His 50 Favorite Children’s Books

Enter an Archive of 6,000 Historical Children’s Books, All Digitized and Free to Read Online

Maurice Sendak Animated; James Gandolfini Reads from Sendak’s Story “In The Night Kitchen”

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities, the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.

One can hardly declare these the best 100 when most of the voters were in their 40s and 50s.

@Kay

Stop being trite, you know how click-bait and the internet rolls.

Well, I will have to quote an old saying; Money talks, bulls**t walks. So when you have enough money to complain, you will be listened to or you will just be known as a crybaby until we old ones die off. Good luck with your future!!

I went to a small rural school in Ohio as an elementary student. It was the same school my Grandfather/Grandmother, Father, aunt, cousins, and seconds attended. The Wild Things were painted on the walls in part of the building. I’ll never forget it. It was a neat building. Before it was torn down, it was open for the community to visit and say goodbye. It’s history. Many memories. I took a pencil sharpener off the wall that had been left behind.

We wore out our hardback copy of “Where the Wild Things Are” and had to get a second one. It was that well-loved.