The animals were imperfect,

long-tailed,

unfortunate in their heads.

Little by little they

put themselves together,

making themselves a landscape,

acquiring spots, grace, flight.

The cat,

only the cat

appeared complete and proud:

he was born completely finished,

walking alone and knowing what he wanted.

- Pablo Neruda, excerpt from Ode to the Cat

We find ourselves in agreement with Nobel Prize-winning poet, and cat lover, Pablo Neruda:

Those of us who provide for felines choose to believe we are “the owner, proprietor, uncle of a cat, companion, colleague, disciple or friend of (our) cat”, when in fact they are mysterious beasts, far more self-contained than the companionable, inquisitive canine Neruda immortalized in Ode to the Dog.

We can bestow names and social media accounts on cats of our acquaintance, channel them on the steps of the Met Gala, attach GPS trackers to their collars, give them pride of placement in books for children and adults, and try our best to get inside their heads, but what do we know about them, really?

We even got their history wrong.

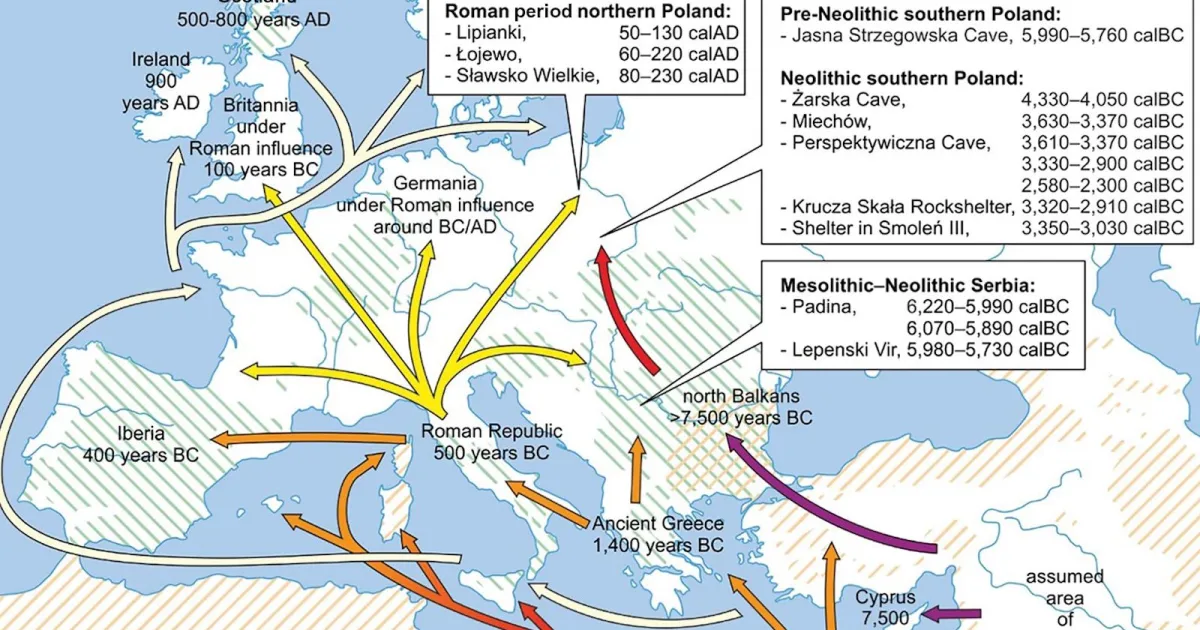

Common knowledge once held that cats made their way to northern Europe from the Mediterranean aboard Roman — and eventually Viking — ships sometime between the 3rd to 7th century CE, but it turns out we were off by millennia.

In 2016, a team of researchers collaborating on the Five Thousand Years of History of Domestic Cats in Central Europe project confirmed the presence of domestic cats during the Roman period in the area that is now northern Poland, using a combination of zooarchaeology, genetics and absolute dating.

More recently, the team turned their attention to Felis bones found in southern Poland and Serbia, determining the ones found in the Jasna Strzegowska Cave to be Pre-Neolithic (5990–5760 BC), while the Serbian kitties hail from the Mesolithic-Neolitic era (6220–5730 BC).

In addition to clarifying our understanding of how our pet cats’ ancestors arrived in Central Europe from Egypt and the Fertile Crescent, the project seeks to “identify phenotypic features related to domestication, such as physical appearance, including body size and coat color; behavior, for example, reduced aggression; and possible physiological adaptations to digest anthropogenic food.”

Regarding non-anthropogenic food, a spike in the Late Neolithic Eastern European house mouse population exhibits some nifty overlap with these ancient cat bones’ newly attached dates, though Dr. Danijela Popović, who supervised the project’s paleogeneticians, reports that the cats’ arrival in Europe preceded that of the first farmers:

These cats probably were still wild animals that naturally colonized Central Europe.

We’re willing to believe they established a bulkhead, then hung around, waiting until the humans showed up before implementing the next phase of their plan — self-domestication.

Read the research team’s “history of the domestic cat in Central Europe” here.

Related Content

A 110-Year-Old Book Illustrated with Photos of Kittens & Cats Taught Kids How to Read

Cats in Medieval Manuscripts & Paintings

via Big Think

– Ayun Halliday, human servant of two feline Mailroom Böyz, is the Chief Primatologist of the East Village Inky zine and author, most recently, of Creative, Not Famous: The Small Potato Manifesto and Creative, Not Famous Activity Book. Follow her @AyunHalliday.

Leave a Reply