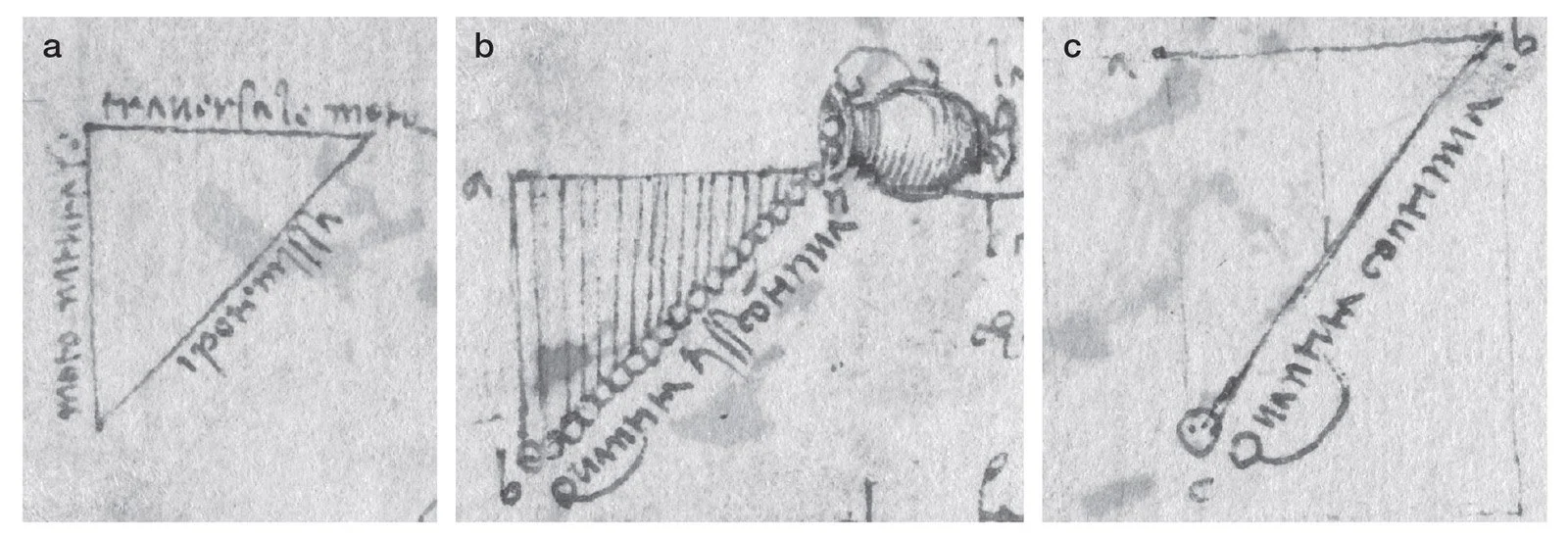

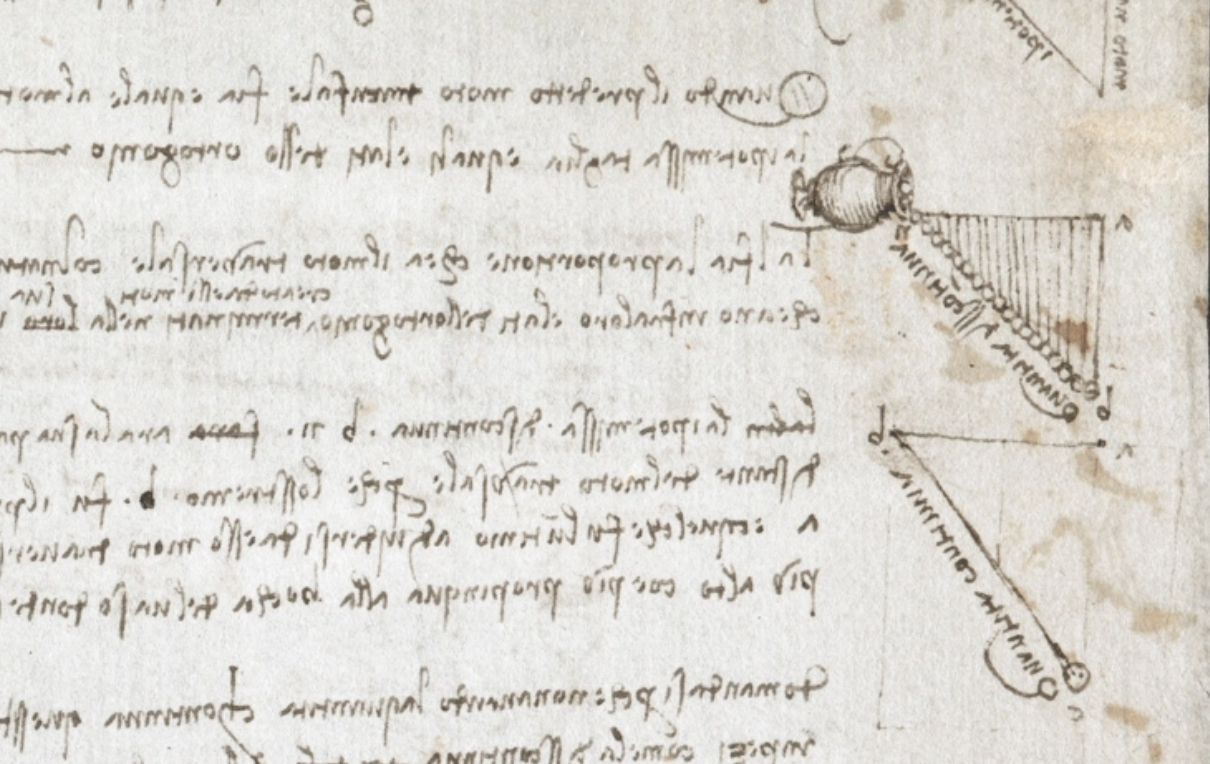

It would be clichéd to describe Leonardo da Vinci as a man ahead of his time. But in the case of the quintessential Renaissance polymath, it may well be one of those clichés firmly rooted in truth. In fact, that rooting has just grown even firmer with the discovery of a triangle that Leonardo sketched in one of his notebooks, the Codex Arundel (circa 1478–1518). That triangle, as the New York Times’ William J. Broad writes, had “an adjoining pitcher and, pouring from its spout, a series of circles that formed the triangle’s hypotenuse.” This image sounds simple, but it reveals that Leonardo approached an understanding of the laws of gravity before Galileo, and well before Newton.

This finding is the work of Morteza Gharib, a professor of aeronautics at the California Institute of Technology. Captivated by this sketch, he “used a computer program to flip the triangle and the adjacent areas of backward writing,” which clarified what Leonardo was attempting to do.

His diagram turned out “to split the effects of gravity into two parts that revealed an aspect of nature normally kept hidden.” The first part was gravity’s “natural downward pull”; the second was the movement of the pitcher itself along a line. That Leonardo drew “the pitcher’s contents falling lower and lower over time” implies his understanding that “gravity was a constant force that resulted in a steady acceleration.”

Along with co-authors Chris Roh and Flavio Noca, Gharib has published a paper on “Leonardo da Vinci’s Visualization of Gravity as a Form of Acceleration” in this month’s issue of Leonardo — an appropriately named journal in this case, though one dedicated less to the study of Leonardo the man than to the study of the intersection of art and science he occupied. As Gharib and others see it, Leonardo “was far more than an artist and suggested that his fame as a pioneering scientist could skyrocket if more technically knowledgeable experts probed the Codex Arundel and other sources” — the kind of experts who can tell that, with his pitcher and triangle, Leonardo managed to determine the strength of gravity’s pull to an accuracy of about 97 percent. Which leads us to wonder: What else about the nature of reality must he have worked out in the margins of his notebooks?

Related Content:

Leonardo da Vinci’s Visionary Notebooks Now Online: Browse 570 Digitized Pages

Leonardo da Vinci’s Elegant Design for a Perpetual Motion Machine

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities, the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.

Leave a Reply