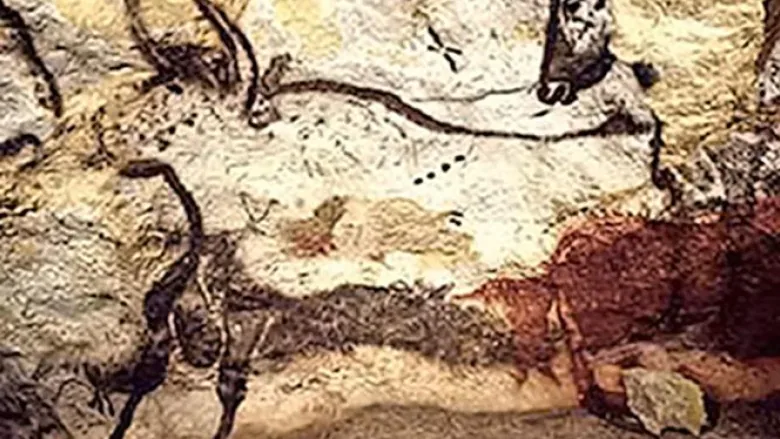

Care to take a guess what your smart phone has in common with Paleolithic cave paintings of Lascaux, Chauvet and Altamira?

Both can be used to track fertility.

Admittedly, you’re probably not using your phone to stay atop the reproductive cycles of reindeer, salmon, and birds, but such information was of critical interest to our hunter-gatherer ancestors.

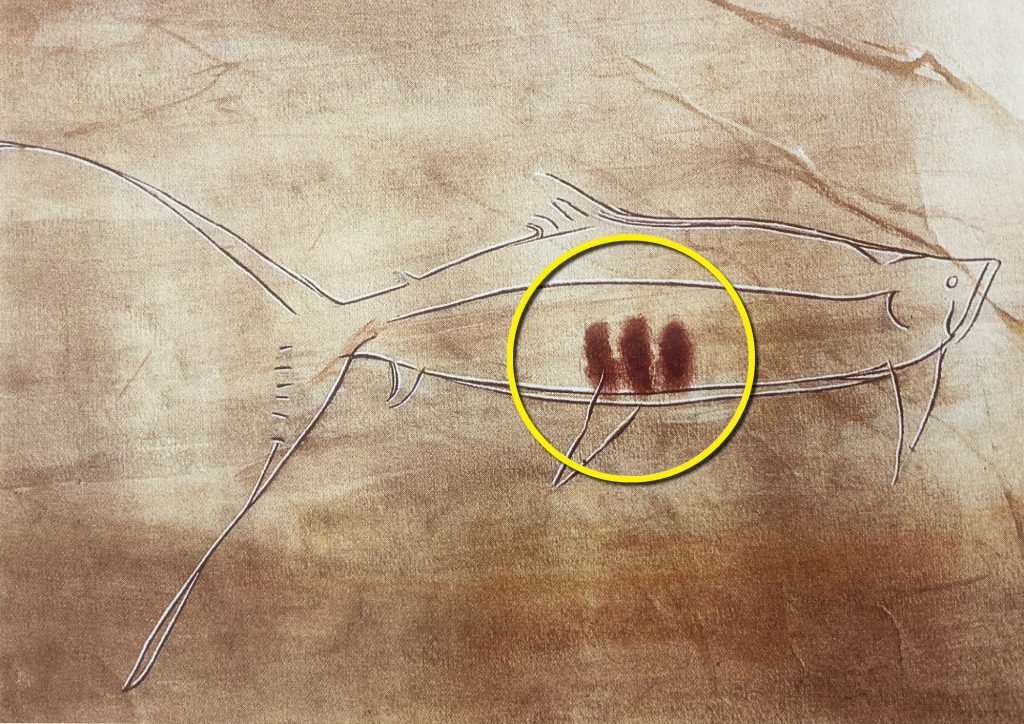

Knowing how crucial an understanding of animal behavior would have been to early humans led London-based furniture conservator Ben Bacon to reconsider what purpose might have been served by non-figurative markings — slashes, dots, and Y‑shapes — on the cave walls’ 20,000-year-old images.

Their meaning had long eluded esteemed professionals. The marks seemed likely to be numeric, but to what end?

Bacon put forward that they documented animal lives, using a lunar calendar.

The amateur researcher assembled a team that included experts from the fields of mathematics, archeology, and psychology, who analyzed the data, compared it to the seasonal behaviors of modern animals, and agreed that the numbers represented by the dots and slashes are not cardinal, but rather an ordinal representation of months.

As Bacon told All Things Considered his fellow self-taught anthropological researcher, science journalist Alexander Marshack, came close to cracking the code in the 1970s:

… but he wasn’t actually able to demonstrate the system because he thought that these individual lines were days. What we did is we said, actually, they’re months because a hunter-gatherer doesn’t need to know what day a reindeer migrates. They need to know what month the reindeer migrates. And once you use these months units, this whole system responds very, very well to that.

As to the frequently occurring symbol that resembles a Y, it indicates the months in which various female animal birthed their young. Bacon and his team theorize in the Cambridge Archeological Journal that this mark may even constitute “the first known example of an ‘action‘ word, i.e. a verb (‘to give birth’).

Taken together, the cave paintings and non-figurative markings tell an age-old circular tale of the migration, birthing and mating of aurochs, birds, bison, caprids, cervids, fish, horses, mammoths, and rhinos … and like snakes and wolverines, too, though they were excluded from the study on basis of “exceptionally low numbers.”

Early humans were able to log months by observing the moon, but how could they tell when a new year had begun, essential information for anyone seeking to arrange their lives around their prey’s previously documented activities?

Bacon and his peers, like so many poets and farmers, look to the rites of spring:

The obvious event is the so-called ‘bonne saison’, a French zooarchaeological term for the time at the end of winter when rivers unfreeze, the snow melts, and the landscape begins to green.

Read the conclusions of their study here.

Related Content

Algerian Cave Paintings Suggest Humans Did Magic Mushrooms 9,000 Years Ago

Was a 32,000-Year-Old Cave Painting the Earliest Form of Cinema?

40,000-Year-Old Symbols Found in Caves Worldwide May Be the Earliest Written Language

- Ayun Halliday is the Chief Primatologist of the East Village Inky zine and author, most recently, of Creative, Not Famous: The Small Potato Manifesto and Creative, Not Famous Activity Book. Follow her @AyunHalliday.

Leave a Reply