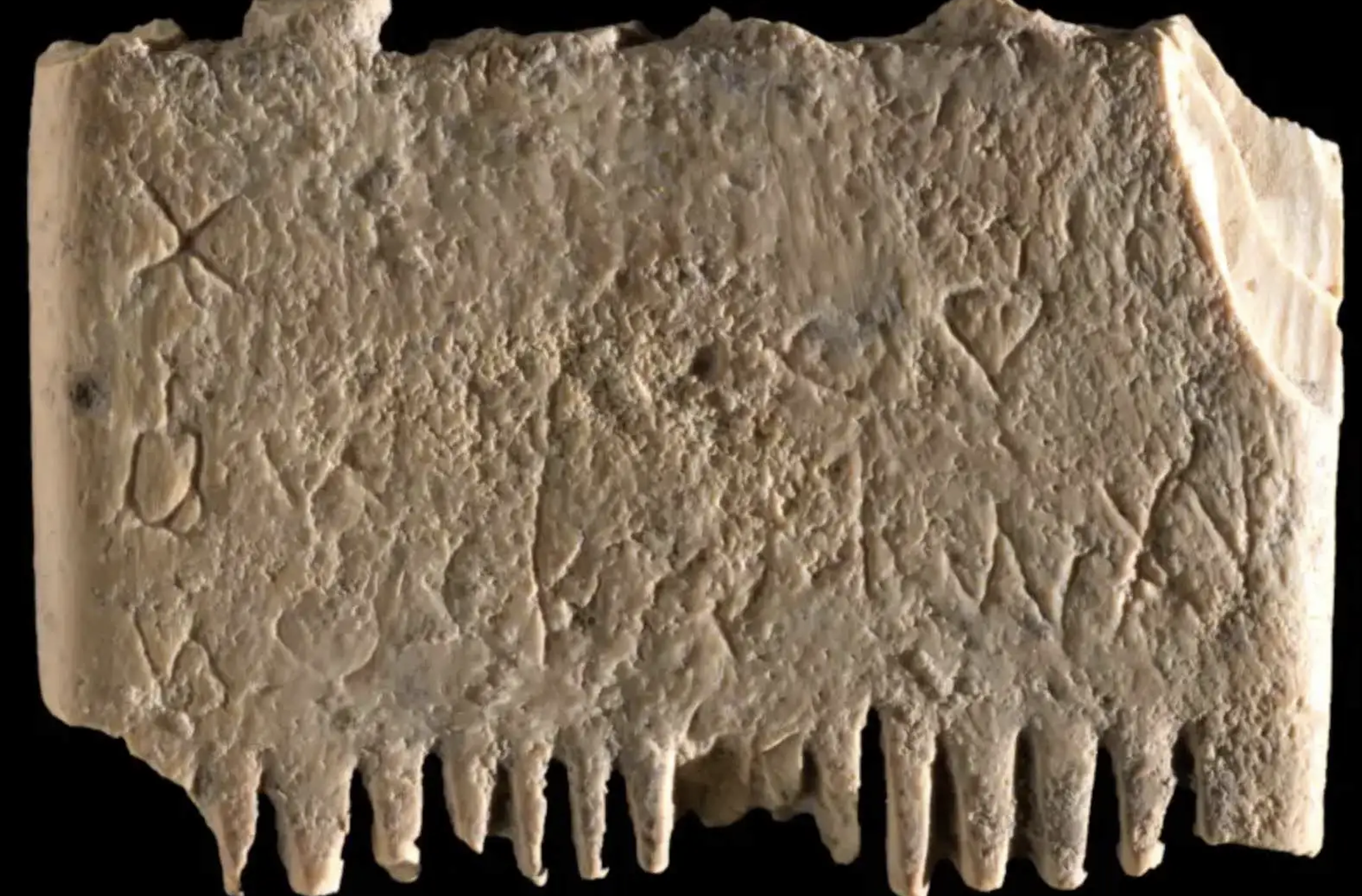

Image by Dafna Gazit, Israel Antiquities Authority

I don’t recall any of my elementary-school classmates looking forward to head-lice inspection day. But had archaeological progress been a few decades more advanced at the time, the teachers might have turned it into a major history lesson. For it was on a comb, designed to remove head lice, that researchers in southern Israel recently found the oldest known sentence written in an alphabet. Invented around 1800 BC, that Canaanite alphabet “was standardized by the Phoenicians in ancient Lebanon,” writes the Guardian’s Ian Sample, later becoming “the foundation for ancient Greek, Latin and most modern languages in Europe today.”

The comb itself, dated to around 1700 BC, bears a simple Canaanite message: “May this tusk root out the lice of the hair and the beard.” As Sample notes, “ancient combs were made from wood, bone and ivory, but the latter would have been expensive, imported luxuries. There were no elephants in Canaan at the time.”

Despite its small size, then, this comb must have been a big-ticket item. The New York Times’ Oliver Whang writes that these facts have already inspired a new set of questions, many of them not strictly linguistic in nature: “Where was the ivory comb inscribed? Who inscribed it? What purpose did the inscription serve?”

As our lice-combating technology has evolved over the millennia, so have our alphabets. From the Canaanite script “the alphabet continued to evolve, from Phoenician to Old Hebrew to Old Aramaic to Ancient Greek to Latin, becoming the basis for today’s modern English characters.” And that wasn’t its only path: Korea, where I live, has a completely different alphabet of its own, but one that caught on for the same reasons as its distant cousins elsewhere in the world. The key is simplicity, as against older writing systems in which one character represented one word or syllable: “Matching one letter to one sound made writing and reading far easier to learn,” Whang writes. Not that some students, even today, wouldn’t submit to the lice comb rather than practice their ABCs.

Related content:

How Writing Has Spread Across the World, from 3000 BC to This Year: An Animated Map

An Ancient Egyptian Homework Assignment from 1800 Years Ago: Some Things Are Truly Timeless

What the Rosetta Stone Actually Says

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities, the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.

Leave a Reply