No matter where you may stand on herbal medicine as a viable 21st-century option, it’s not hard to imagine we’d have all been true believers back in the 15th-century.

In an article for Heart Views, cardiologist Rachel Hajar lists some common herbal treatments of the Middle Ages:

Headache and aching joints were treated with sweet-smelling herbs such as rose, lavender, sage, and hay. A mixture of henbane and hemlock was applied to aching joints. Coriander was used to reduce fever. Stomach pains and sickness were treated with wormwood, mint, and balm. Lung problems were treated with a medicine made of liquorice and comfrey. Cough syrups and drinks were prescribed for chest and head-colds and coughs.

If nothing else, such approaches sound rather more pleasant than bloodletting.

Monks were responsible for the study and cultivation of medicinal herbs.

You may recall how one of Friar Lawrence’s daily tasks in Romeo and Juliet involved venturing into the monastery garden, to fill his basket full “baleful weeds and precious-juicèd flowers.”

(The powerful sleeping potion he concocted for the young lovers may have had disastrous consequences, but no one can claim it wasn’t effective.)

Monks preserved their herbal knowledge in illustrated books and manuscripts, many of which cleaved closely to works of classical antiquity such as Pliny the Elder’s Naturalis Historia and Dioscordes’ De Materia Medica.

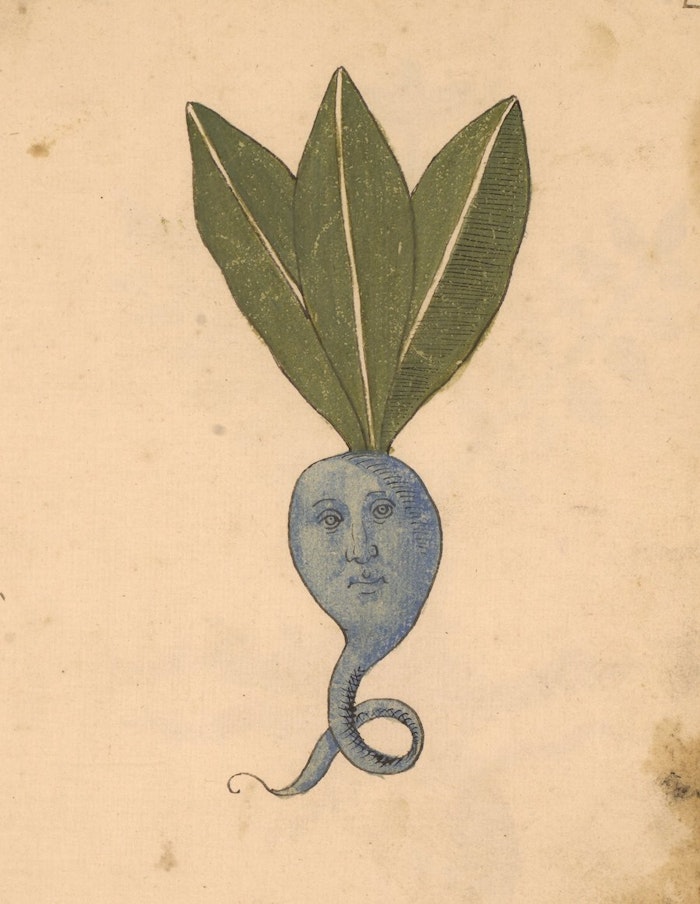

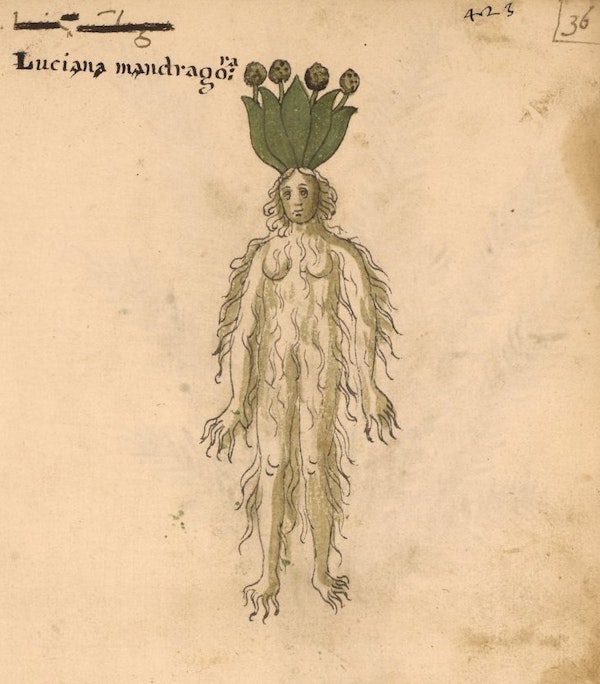

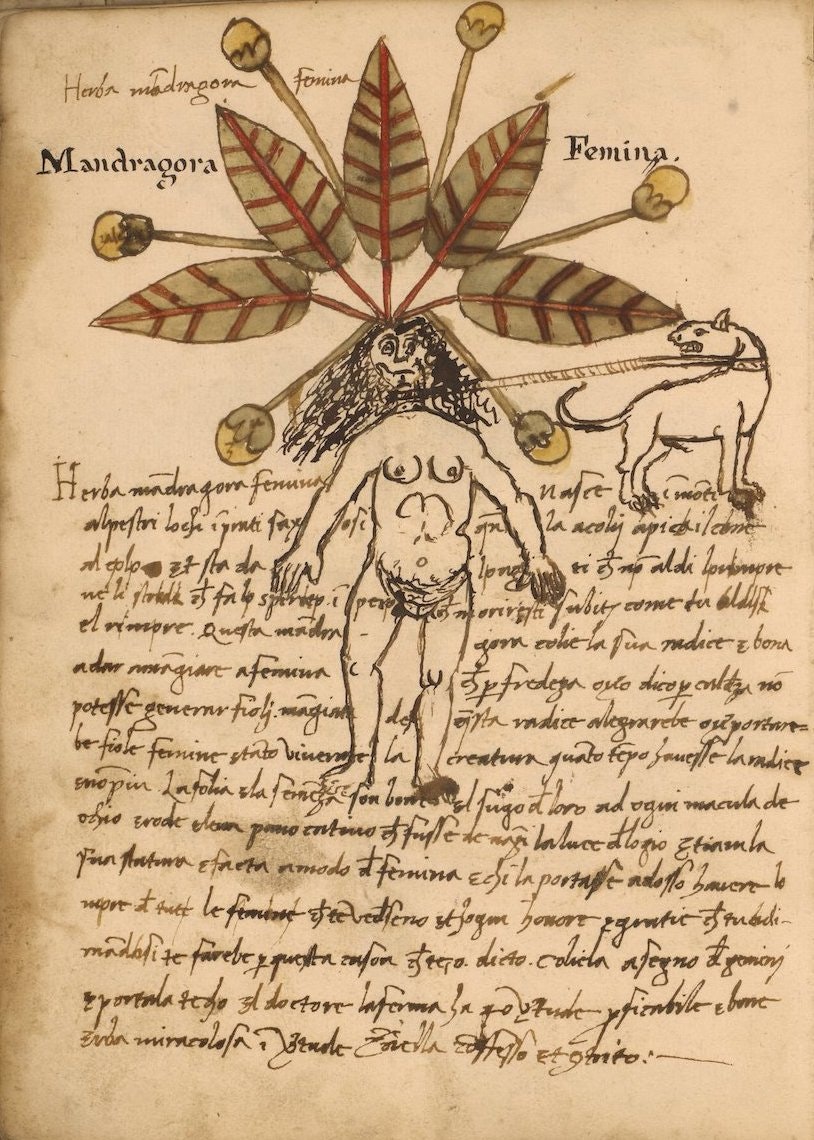

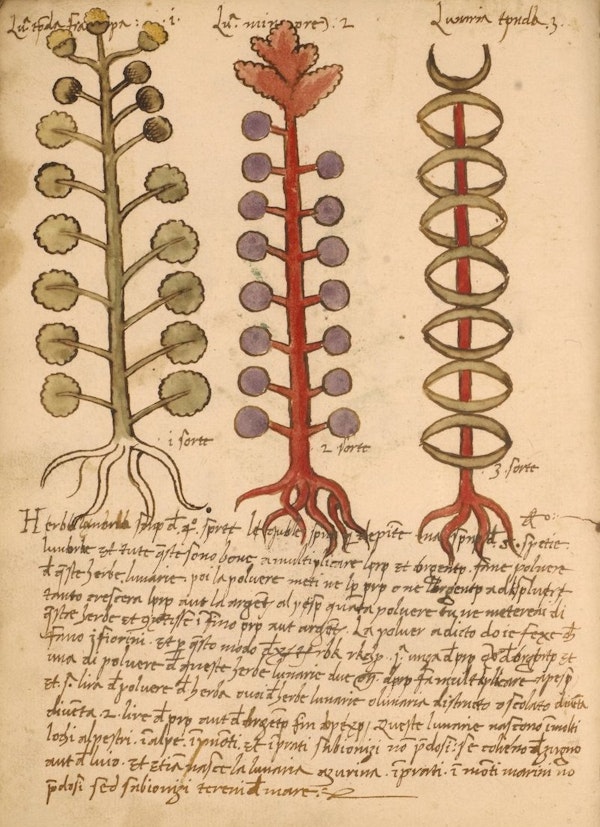

These early medical texts can still be appreciated as art, particularly when they contain fantastical embellishments such as can be seen in Erbario, above, a handmade 15th-century herbal from northern Italy that was recently added to the University of Pennsylvania Library’s collection of rare books and manuscripts.

In addition to straightforward botanical illustrations, there are some roots, leaves, flowers and fruit (pardon the pronoun) of a decidedly anthropomorphic bent.

Fancying up drawings of plants with human faces and or dragon-shaped roots was a medieval convention.

Mandrake roots — prescribed as an anesthetic, an aphrodisiac, a fertility booster, and a sleep aid — were frequently rendered as humans.

Wired’s Matt Simon writes that mandrake roots “can look bizarrely like a human body and legend holds that it can even come in male and female form:”

It’s said to spring from the dripping fat and blood and semen of a hanged man. Dare pull it the from the earth and it lets out a monstrous scream, bestowing agony and death to all those within earshot.

Yikes! Can we get a spoonful of sugar to help that go down?

No wonder Juliet, preparing to quaff Friar Lawrence’s sleeping potion in the family tomb, fretted that it might wear off prematurely, leaving her subject to “loathsome smells” and “shrieks like mandrakes torn out of the earth.”

Methinks some chamomile might have calmed those nerves…

View a digitized copy of Erbario here, or at the Public Domain Review.

Related Content

1,000-Year-Old Illustrated Guide to the Medicinal Use of Plants Now Digitized & Put Online

A Beautiful 1897 Illustrated Book Shows How Flowers Become Art Nouveau Designs

- Ayun Halliday is the Chief Primatologist of the East Village Inky zine and author, most recently, of Creative, Not Famous: The Small Potato Manifesto. Follow her @AyunHalliday.

Leave a Reply