“Old paint on a canvas, as it ages, sometimes becomes transparent,” playwright Lillian Hellman observed in Pentimento, the second volume of her memoirs. “When that happens it is possible, in some pictures, to see the original lines: a tree will show through a woman’s dress, a child makes way for a dog, a large boat is no longer on an open sea.”

Seven years ago, something similar started happening with thousands of old books, dating from the 15th to 19th century.

Age, however, didn’t force these volumes to spill their secrets…at least not directly.

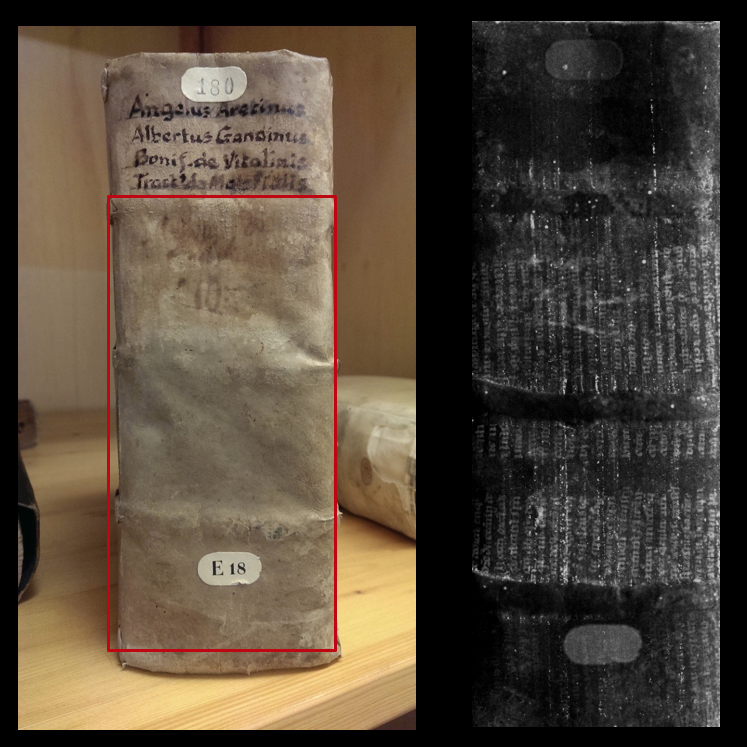

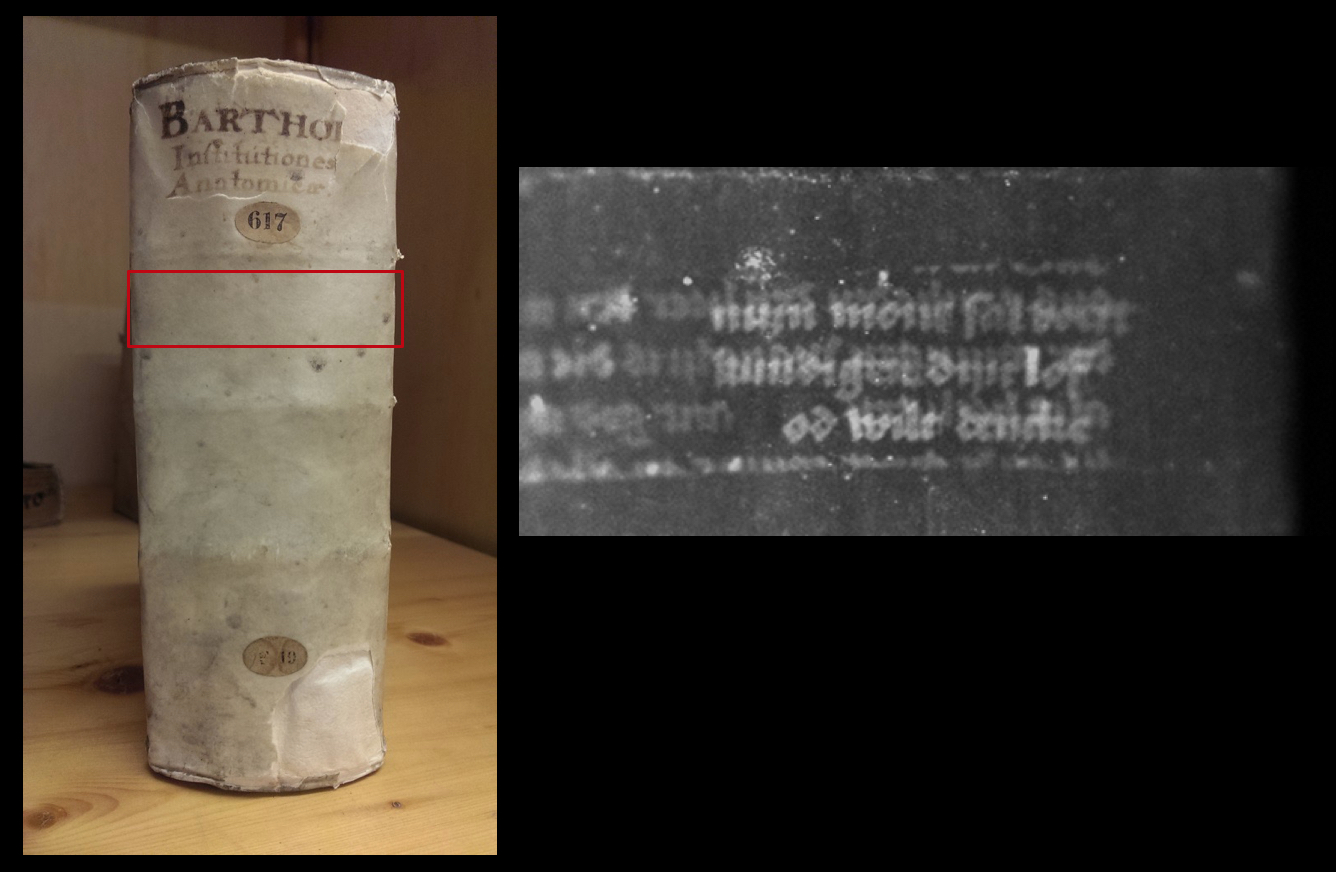

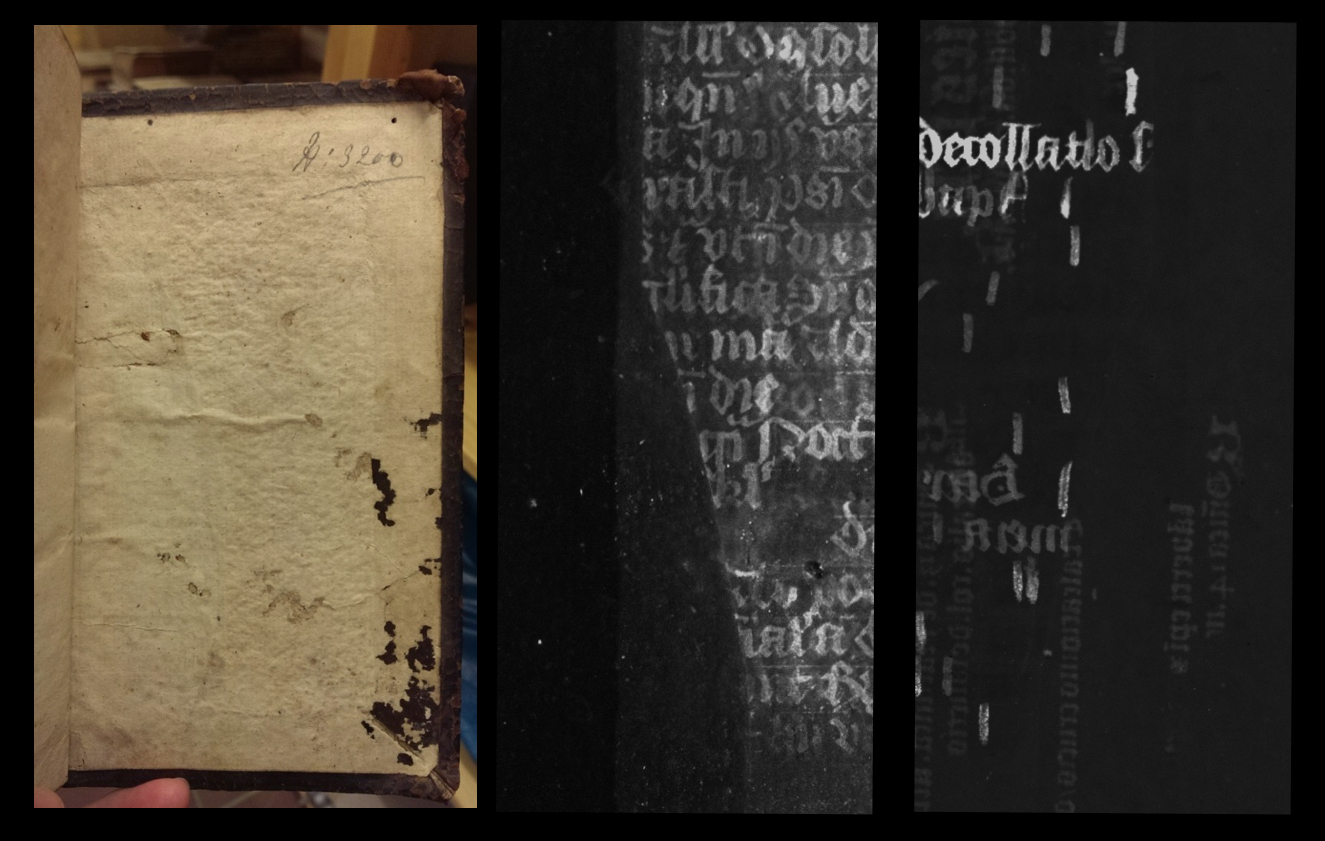

That honor goes to macro X‑ray fluorescence spectrometry (MA-XRF) and Erik Kwakkel, a book historian who theorized that this technology might reveal medieval manuscript fragments hidden in the bindings of newer texts, much as it had earlier revealed hidden layers of paint on Old Master canvases.

How did this strange “hidden library” come to be?

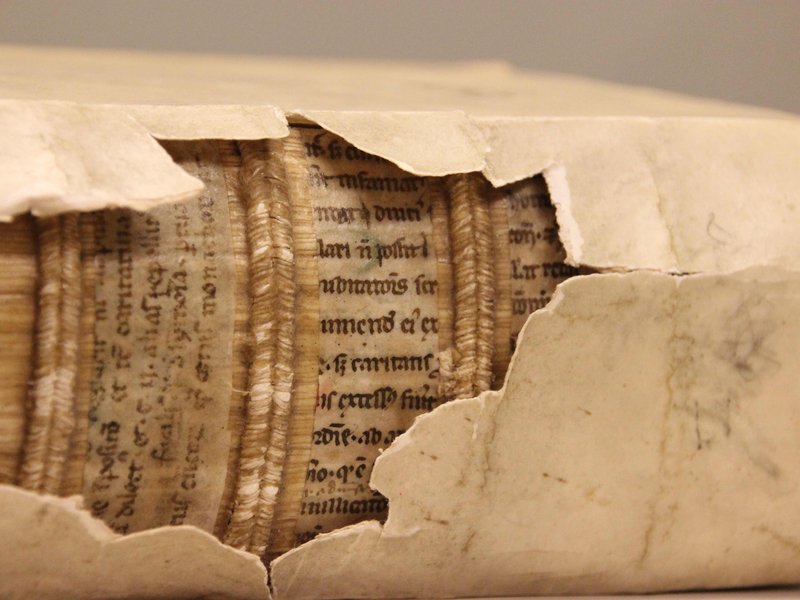

Books were highly prized objects when manuscripts were copied by hand, but as Kwakkel notes on his medievalbooks blog, “thousands and thousands of medieval manuscripts were torn apart, ripped to pieces, boiled, burned, and stripped for parts” upon the advent of the printing press.

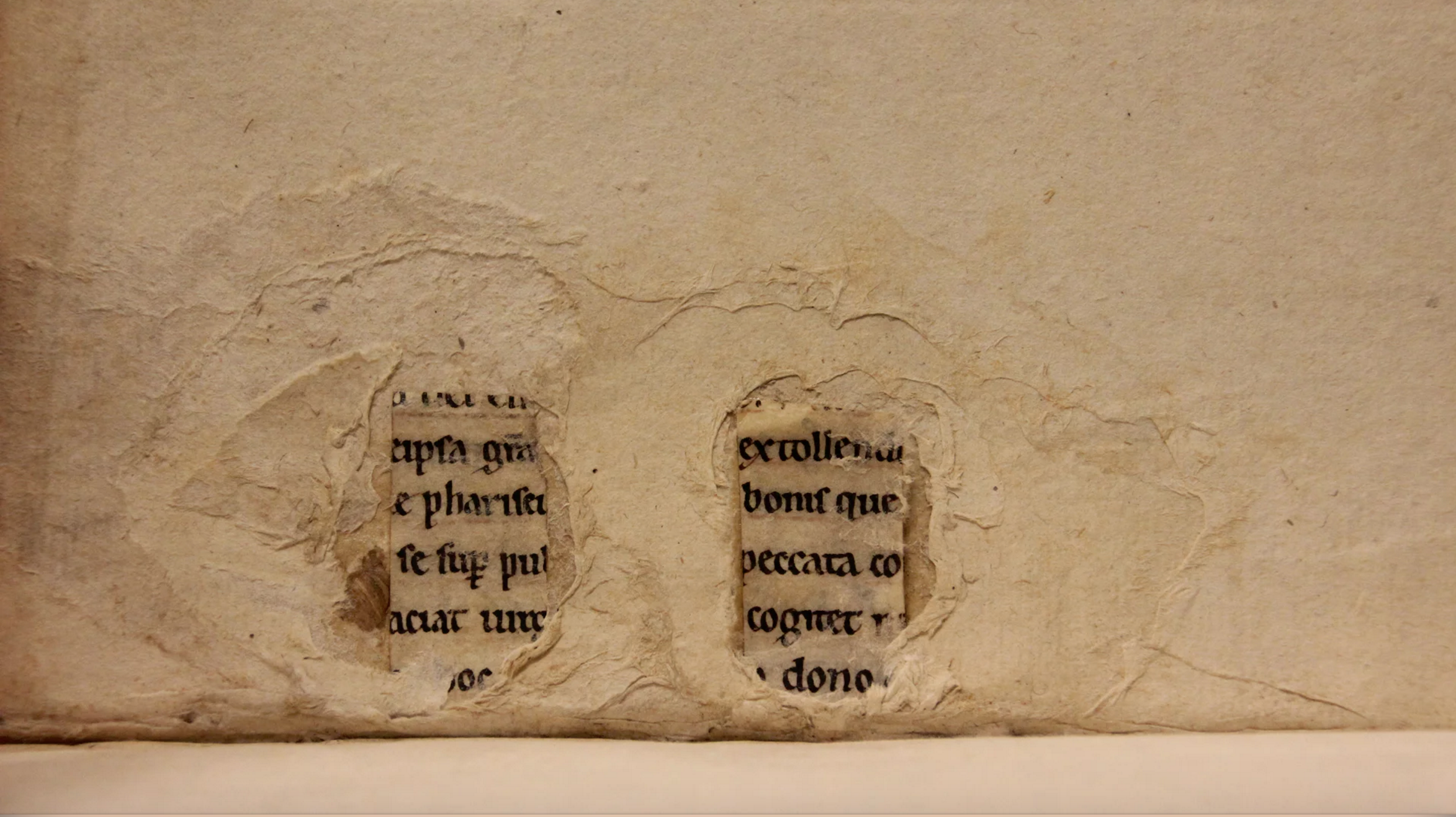

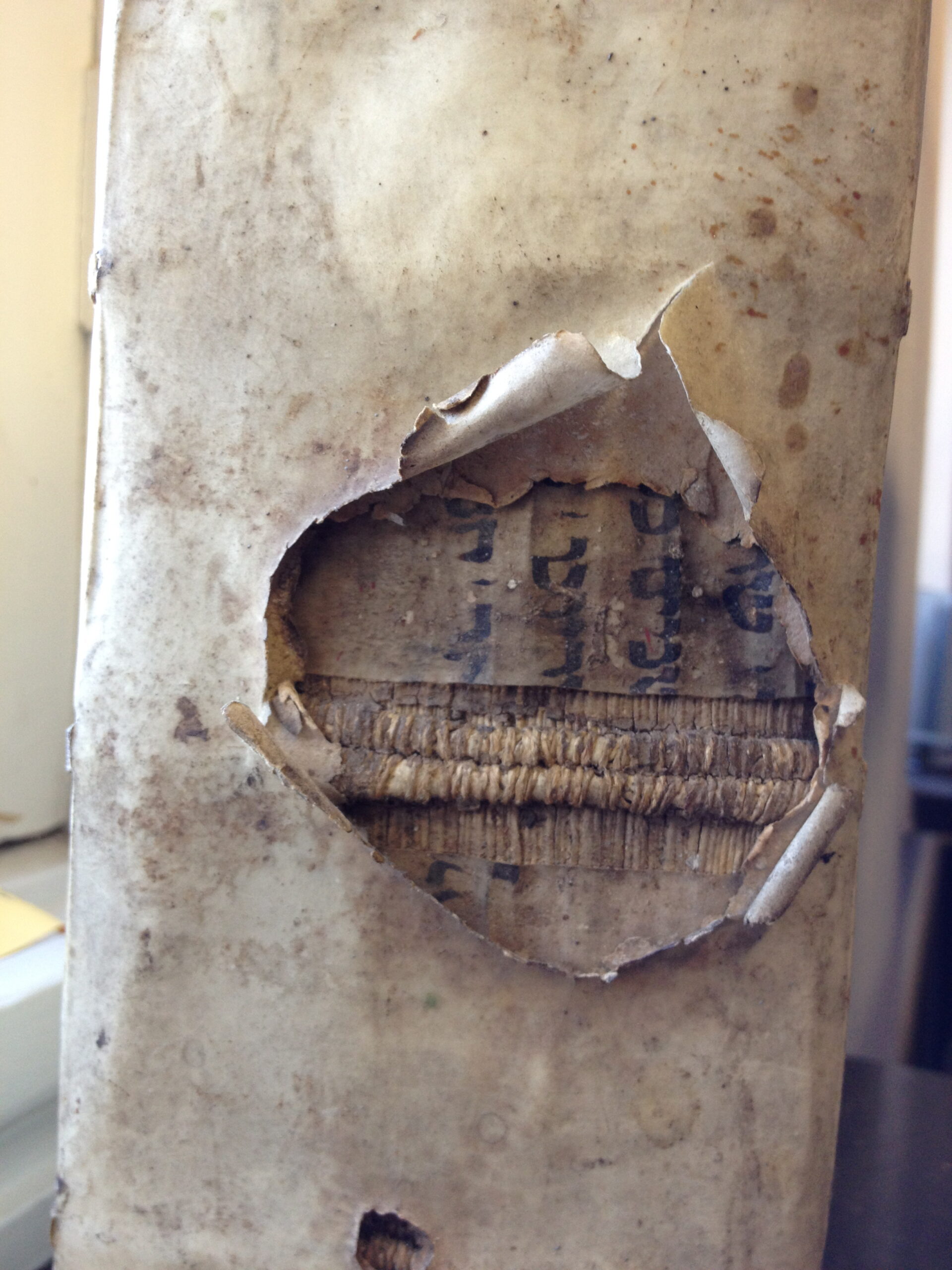

Their pages were pressed into service as toilet paper, bukram-like clothing stiffeners, bookmarks, and, most tantalizing to a medieval book specialist, binding support for printed books.

This practice was so common that the bindings of nearly 150 early printed books in the Yale Law Library are known to contain pieces of medieval manuscripts.

These materials may have been downgraded in the literary sense, but to Kwakkel they are “travelers in time, stowaways in leather cases with great and important stories to tell:”

Indeed, stories that may otherwise not have survived, given that classical and medieval texts frequently only come down to us in fragmentary form. The early history of the Bible as a book could not be written if we were to throw out fragment evidence. Moreover, while ancient and medieval texts survive in many handsome books from before the age of print, quite often the oldest witnesses are fragments. At the very least a fragment tells you that a certain text was available at a certain location at a certain time. Stepping out of their leather time capsules after centuries of darkness, fragments are “blips” on the map of Europe, expressing “I existed, I was used by a reader in tenth-century Italy!”

A few lines of a mutilated text can often be sufficient to identify it, as well as the location and general timing of its creation:

That said, it is not easy to make sense of the remains. Binders seem to have particularly enjoyed slicing text columns in half, as if they knew how to frustrate future researchers best. Identifying what works these unfulfilling quotes come from can be a nightmare. Dating and localizing the remains can cause insomnia.

Prior to Kwakkel’s high tech experiments at Leiden University, modern researchers had to confine themselves to accidents, as when, say, an old book’s spine cracks, revealing the contents within.

Macro X‑ray fluorescence spectrometry turns out to be well equipped to detect the iron, copper and zinc of medieval inks beneath a layer of paper or parchment.

But it does so at a pace that might not knock a medieval scribe’s socks off.

Producing a legible scan of what lurks beneath a single volume’s spine can require as much as 24 hours, and expensive and time consuming proposition.

With thousands of these bindings hiding so close to the surface in collections as massive as the British Library and Oxford’s Bodleian, be prepared to remain on your tenterhooks for the foreseeable future.

If you would like to sign up for Open Culture’s free email newsletter, please find it here. It’s a great way to see our new posts, all bundled in one email, each day.

If you would like to support the mission of Open Culture, consider making a donation to our site. It’s hard to rely 100% on ads, and your contributions will help us continue providing the best free cultural and educational materials to learners everywhere. You can contribute through PayPal, Patreon, and Venmo (@openculture). Thanks!

via Messy Nessy

Related Content

A Medieval Book That Opens Six Different Ways, Revealing Six Different Books in One

Cats in Medieval Manuscripts & Paintings

- Ayun Halliday is the Chief Primatologist of the East Village Inky zine and author, most recently, of Creative, Not Famous: The Small Potato Manifesto. Join her in New York City on November 11 to create a collaborative Kurt Vonnegut Centennial fanzine. Follow her @AyunHalliday.

Leave a Reply