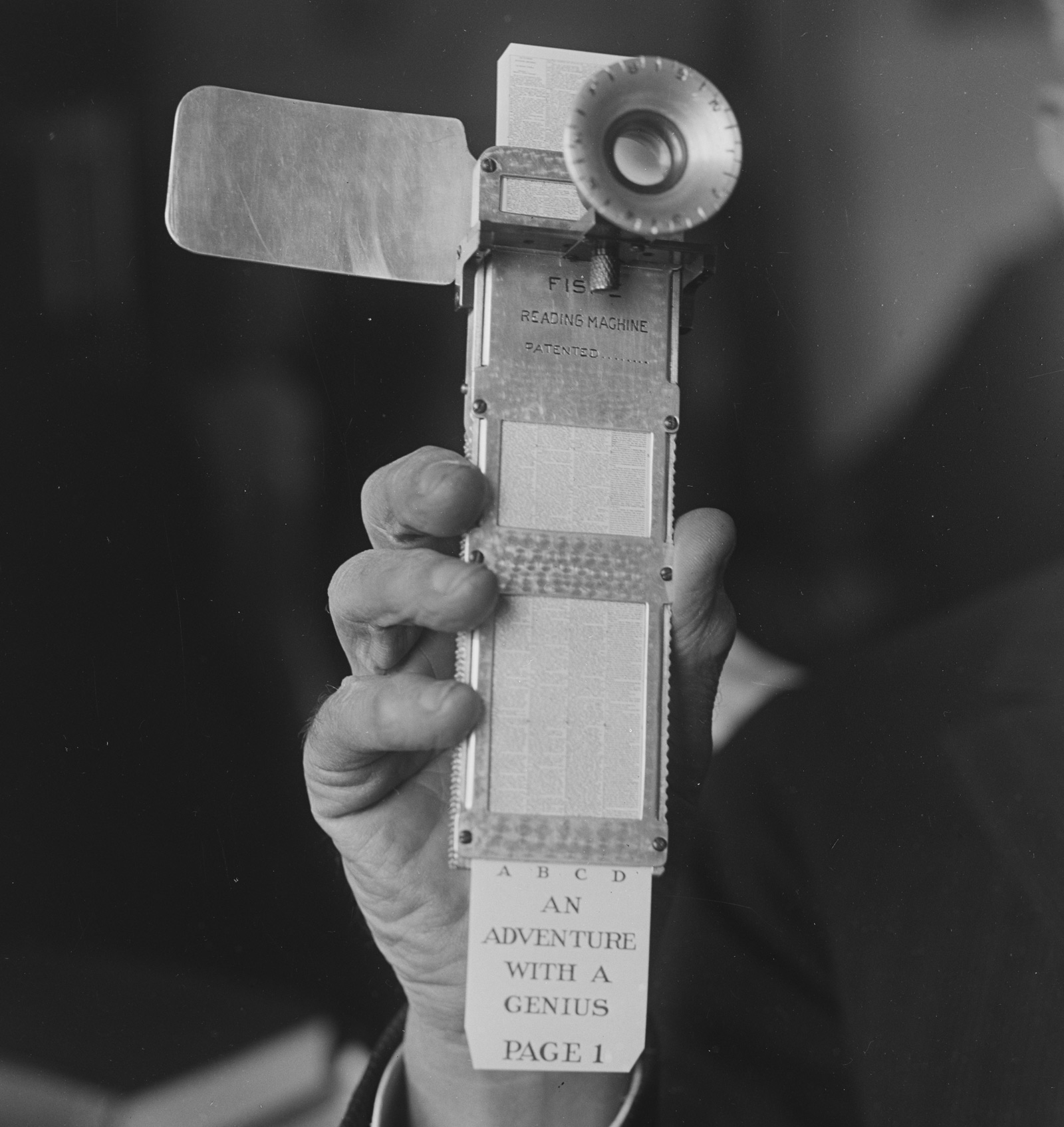

The Sony Librie, the first e‑reader to use a modern electronic-paper screen, came out in 2004. Old as that is in tech years, the basic idea of a handheld device that can store large amounts of text stretches at least eight decades farther back in history. Witness the Fiske Reading Machine, an invention first profiled in a 1922 issue of Scientific American. “The instrument, consisting of a tiny lens and a small roller for operating this eyepiece up and down a vertical column of reading-matter, is a means by which ordinary typewritten copy, when photographically reduced to one-hundredth of the space originally occupied, can be read with quite the facility that the impression of conventional printing type is now revealed to the unaided eye,” writes author S. R. Winters.

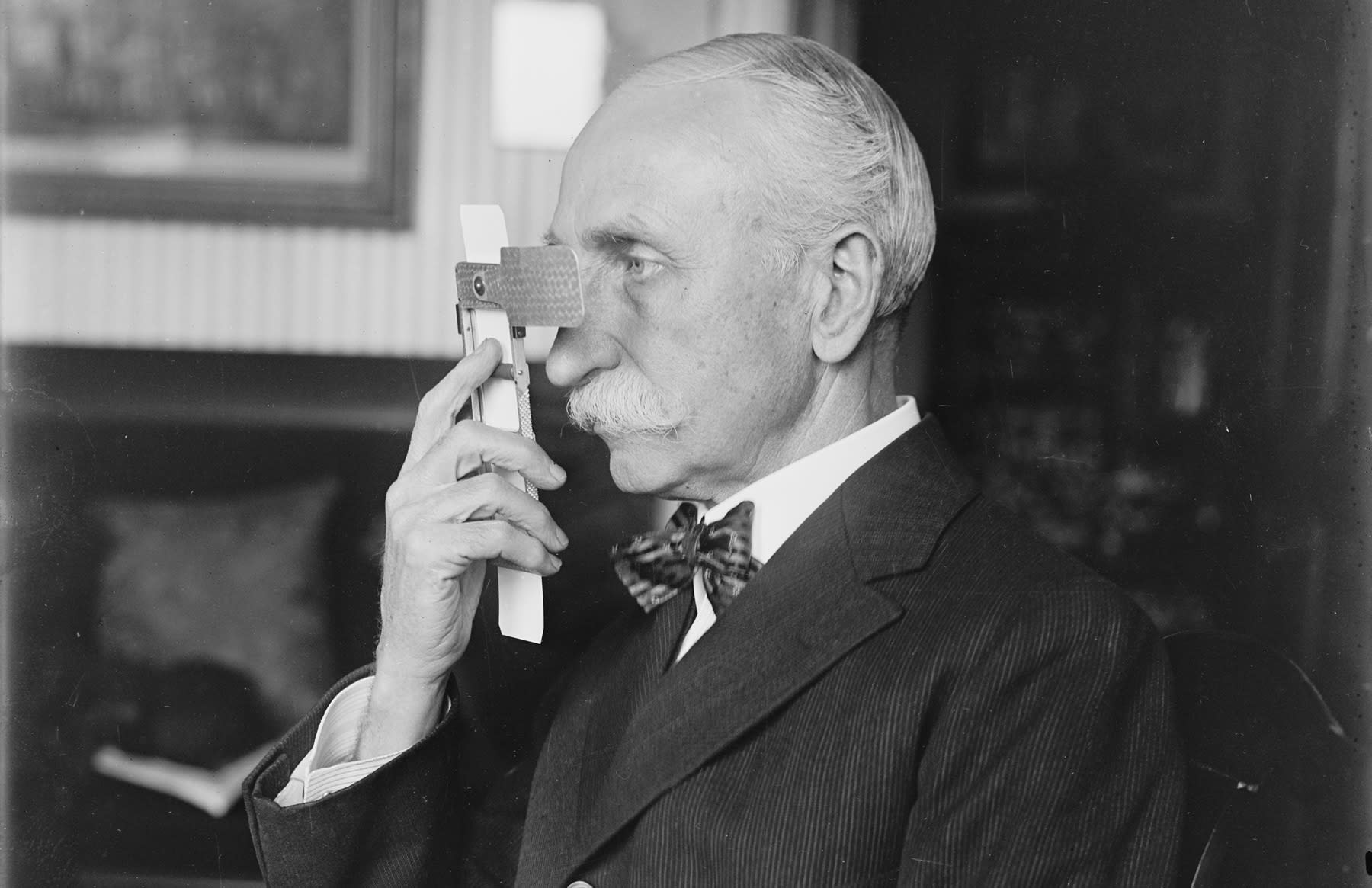

Making books compatible with the Fiske Reading Machine involved not digitization, of course, but miniaturization. According to the patents filed by inventor Bradley Allen Fiske (eleven in all, between 1920 and 1935), the text of any book could be photo-engraved onto a copper block, reduced ten times in the process, and then printed onto strips of paper for use in the machine, which would make them readable again through a magnifying lens. A single magnifying lens, that is: “A blinder, attached to the machine, can be operated in obstructing the view of the unused eye.” (Winters adds that “the use of both eyes will doubtless involve the construction of a unit of the reading machine more elaborate than the present design.”)

“Fiske believed he had single-handedly revolutionized the publishing industry,” writes Engadget’s J. Rigg. “Thanks to his ingenuity, books and magazines could be produced for a fraction of their current price. The cost of materials, presses, shipping and the burden of storage could also be slashed. He imagined magazines could be distributed by post for next to nothing, and most powerfully, that publishing in his format would allow everyone access to educational material and entertainment no matter their level of income.” Considering how the relationship between readers and reading material ultimately evolved, thanks not to copper blocks and magnifiers and tiny strips of paper but to computers and the internet, it seems that Fiske was a man ahead of his time.

Alas, the Fiske Reading Machine itself was just on the wrong side of technological history. Even as Fiske was refining its design, “microfilm was beginning to catch on,” and “while it initially found its feet in the business world — for keeping record of cancelled checks, for example — by 1935 Kodak had begun publishing The New York Times on 35mm microfilm.” Despite the absolute prevalence that format soon attained in the world of archiving, “the appetite for miniaturized novels and handheld readers never materialized in the way Fiske had imagined.” Nor, surely, could he have imagined the form the digital, electronic-paper-screened, and slim yet hugely capacious form that the e‑reader would have to take before finding success in the marketplace — yet somehow without quite displacing the paper book as even he knew it.

via Engadget

Related content:

Napoleon’s Kindle: See the Miniaturized Traveling Library He Took on Military Campaigns

The Page Turner: A Fabulous Rube Goldberg Machine for Readers

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities, the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.

Leave a Reply