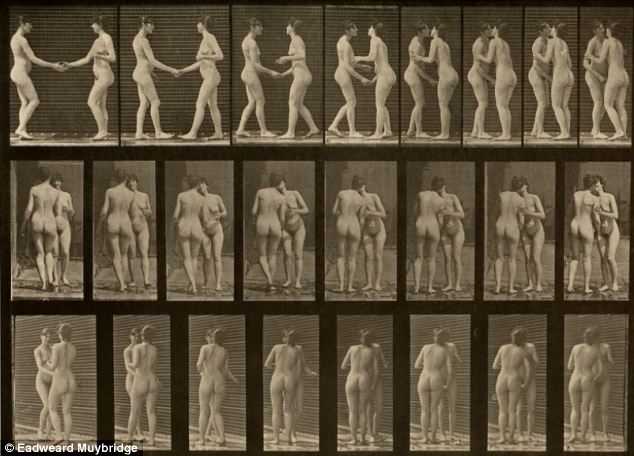

Every moving image we watch today descends, in a sense, from the work of Eadweard Muybridge. In the 1870s he devised a method of photographing the movements of animals, a study he expanded to humans in the 1880s. This constituted a leap toward the development of cinema, though you wouldn’t necessarily know it by looking at the best-known images he produced, such as the set of cards known as The Horse in Motion. You may get a more vivid sense of his photography’s import by seeing it in animated GIF form, as previously featured here on Open Culture, including the very first kiss on film.

Though he often worked with nude models, “Muybridge was not into smut and eroticism,” says Flashbak. “His rapid-fire sequential photographs of two naked women kissing served to aid his studies of human and animal movement. It was in the interests of art and science Muybridge secured the services of two women, invited them to undress and photographed them kissing.” This turns out to be somewhat more plausible than it sounds: the Muybridge online archive notes that “because of Victorian sexual taboos Muybridge was not able to photograph men and women naked together,” and in any case it was commonly believed that “women had little or no sex drive.”

Whatever its relationship to public morality at the time, Muybridge’s kiss suggested the shape of things to come. For a long time after the invention of cinema, writes the New York Times’ A. O. Scott, “a kiss was all the sex you could show on-screen.” Today, “we sometimes look back on old movies as artifacts of an innocent, more repressive time,” but the rich history of “the cinematic kiss” reveals “yearning and hostility, defiance and pleading, male domination and female assertion. There are unlikely physical contortions and suggestive compositions, sometimes imposed by the anti-lust provisions of the code” — the censorious “Hays Code” that restricted the content of American movies between 1934 and 1968 — “sometimes by the desire to breathe new formal life into a weary convention.” Muybridge may have been the first to figure out how to capture a kiss, but generations of filmmakers have had to reinvent the practice over and over ever since.

Related content:

Watch After the Ball, the 1897 “Adult” Film by Pioneering Director Georges Méliès (Almost NSFW)

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities, the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.

Quite a montage…. https://youtu.be/XFZqrcqKGhY