Oh to go behind the scenes at a world class museum, to discover treasures that the public never sees.

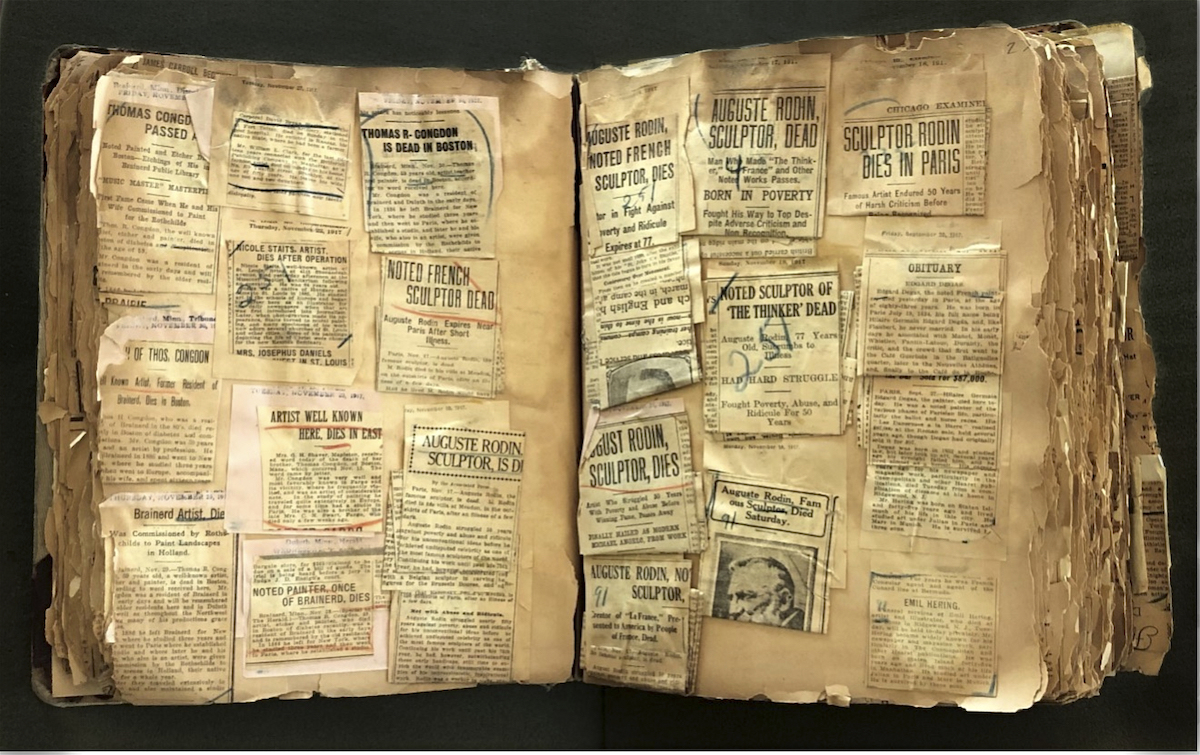

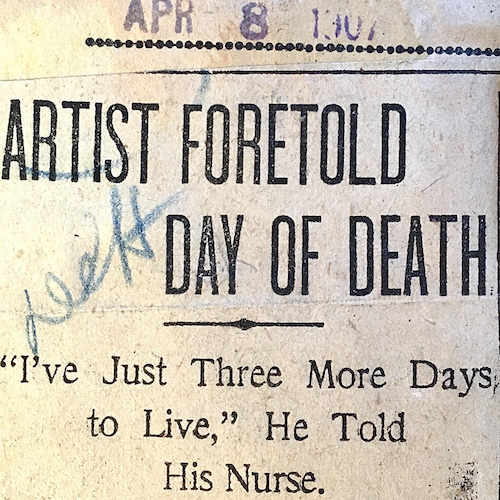

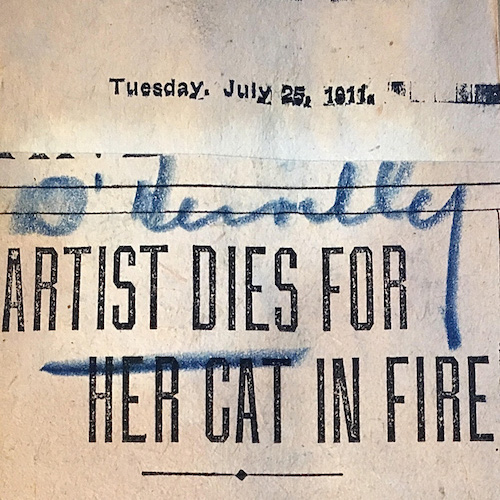

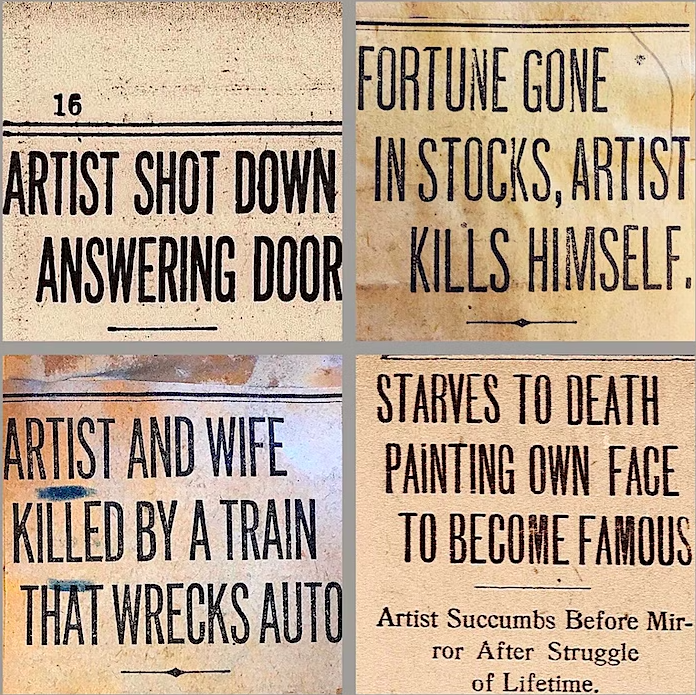

Among the most compelling — and unexpected — at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City are a pair of crumbing scrapbooks, their pages thick with yellowing obituaries and death notices for a wide array of late 19th and early 20th-century painters, sculptors, and photographers.

Some names, like Auguste Rodin or Jules Breton, are still familiar to many 21st-century art lovers.

Others, like Francis Davis Millet, who served as a Union Army drummer boy during the Civil War and perished on the Titanic, were much admired in their day, but have largely faded from memory.

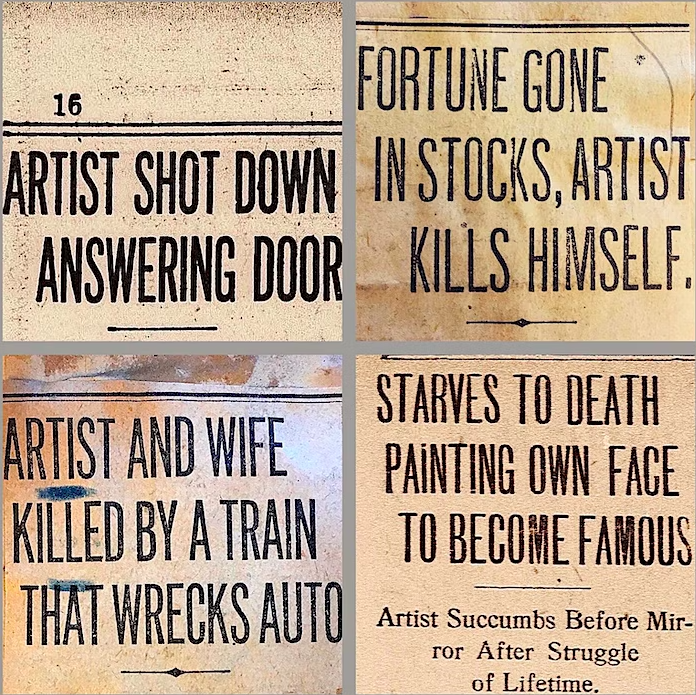

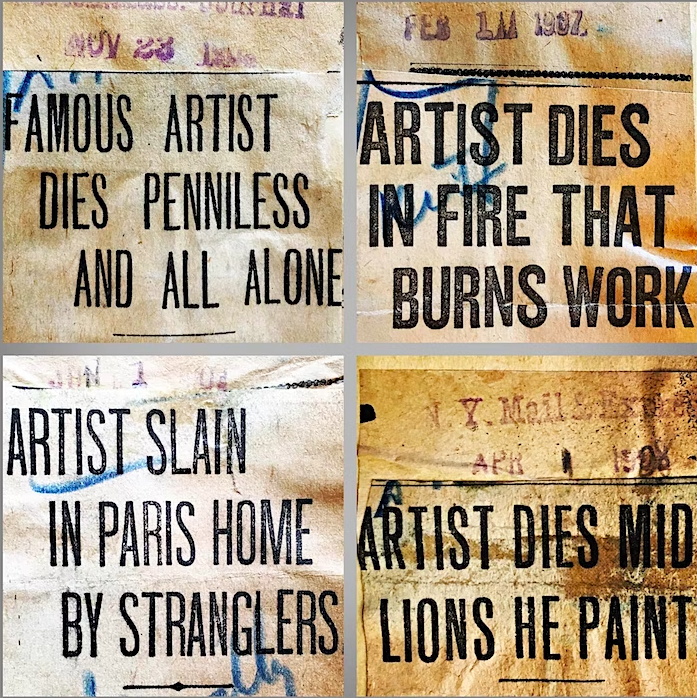

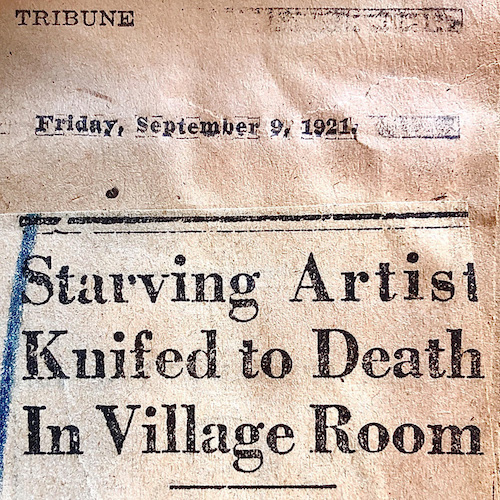

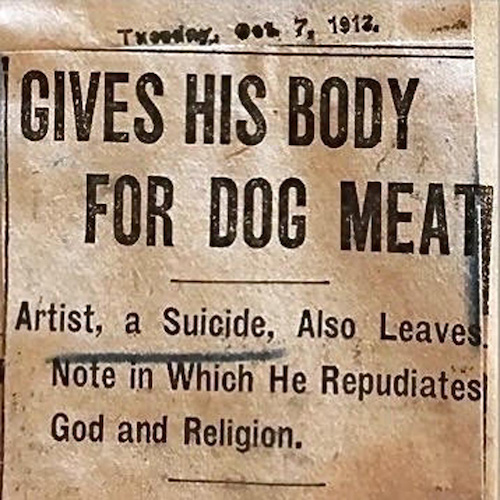

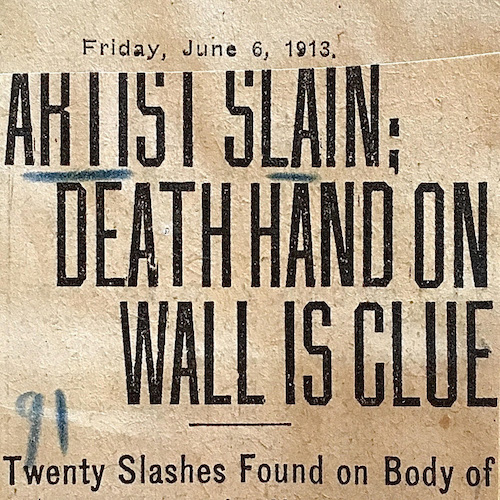

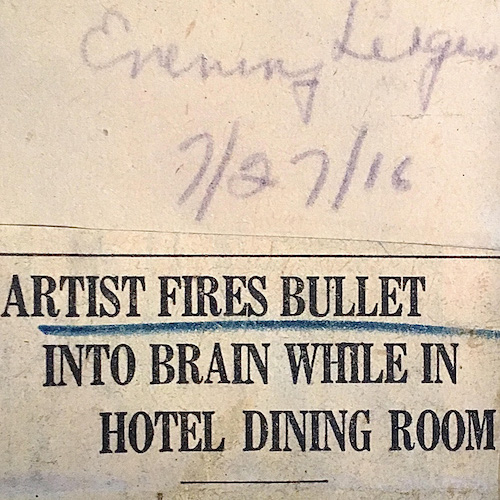

The vast majority are requiems of a sort for those who toiled in obscurity. They may not have received much attention in life, but the circumstances of their deaths by suicide, murder, or bizarre accident had the whiff of the penny dreadful, a quality that could move a lot of newspapers. The deceased’s addresses were published, along with their names. Any tragic detail was sure to be heightened for effect, the tawdrier the better.

As the Met’s Managing Archivist, Jim Moske, who unearthed the scrapbooks four years ago while prowling for historic material for the museum’s 150th anniversary celebration, writes in Lit Hub:

Typical of the era’s crass tabloid journalism, they were crafted to wring maximum drama out of misfortune, and to excite and fix the attention of readers susceptible to raw emotional appeal and voyeurism. Their authors drew upon and reinforced stereotypes of artists as indigent, debauched, obsessed with greatness, eccentric, or suffering from mental illness.

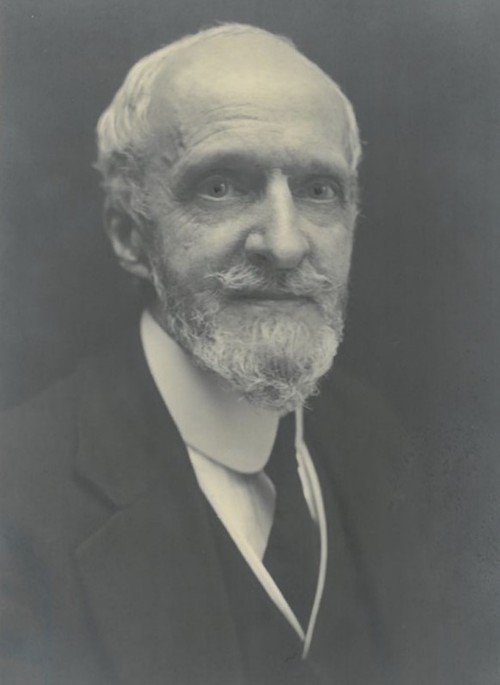

It took Moske a fair amount of digging to identify the creator of these scrapbooks, one Arturo B. de St. M. D’Hervilly.

D’Hervilly spent a decade working in various administrative capacities before being promoted to Assistant Curator of Paintings. A dedicated employee and talented artist himself, D’Hervilly put his calligraphic skills to work crafting illuminated manuscript-style keepsakes for the families of recently deceased trustees and locker room signs.

In a recent lecture hosted by the Victorian Society of New York, Moske noted that D’Hervilly understood that the museum could use newspapers for self-documentation as well promotion.

To that end, the Met maintained accounts with a number of clippings bureaus, media monitoring services whose young female workers pored over hundreds of daily newspapers in search of target phrases and names.

Think of them as an analog, paid precursor to Google Alerts.

Many of the clippings in the scrapbook bear the initials “D’H” or D’Hervilly’s surname, scrawled in the same blue crayon the National Press Intelligence Company and other clippings bureaus used to underline the target phrase.

Moske theorizes that D’Hervilly may have been using the Met’s account to pursue a personal interest in collecting these types of notices:

Newly promoted to curate masterpiece paintings, had he given up for good his own artistic ambition? Was the composition of these morbid tomes a veiled acknowledgement of the passing away of his creative aspiration? Did he identify with the hundreds of uncelebrated artists whose fates the news clippings recorded in grim detail? Perhaps, instead, his intent was more mundane, and compiling them was an expedient for collecting useful biographical data as he catalogued pictures in the Met collection that were made by recently deceased artists.

Many of the hundreds of clippings he preserved appear to be the only traces remaining of these artists’ creative existence on this earth.

After D’Hervilly suffered a fatal heart attack while getting ready to leave for work on the morning April 7, 1919, his colleagues took over his pet project, adding to the scrapbooks for another next ten years.

In researching the scrapbooks’ author’s life, Moske was able to truffle up scant evidence of D’Hervilly’s extracurricular creative output — just one painting in a catalogue of an 1887 National Academy of Design exhibition — but a 1919 clipping, dutifully pasted (posthumously, of course) into one of the scrapbooks, identified the longtime Met employee as a “SLAVE OF DUTY AT ART MUSEUM”, who never took time off for holidays or even luncheon, preferring to eat at his desk.

Related Content

Take a New Virtual Reality Tour of the Metropolitan Museum of Art

Download 584 Free Art Books from The Metropolitan Museum of Art

The Metropolitan Museum of Art Puts 400,000 High-Res Images Online & Makes Them Free to Use

- Ayun Halliday is the Chief Primatologist of the East Village Inky zine and author, most recently, of Creative, Not Famous: The Small Potato Manifesto. Follow her @AyunHalliday.

Leave a Reply