Renaissance artist Albrecht Dürer (1471–1528) never saw a rhino himself, but by relying on eyewitness descriptions of the one King Manuel I of Portugal intended as a gift to the Pope, he managed to render a fairly realistic one, all things considered.

Medieval artists’ renderings of cats so often fell short of the mark, Youtuber Art Deco wonders if any of them had seen a cat before.

Point taken, but cats were well integrated into medieval society.

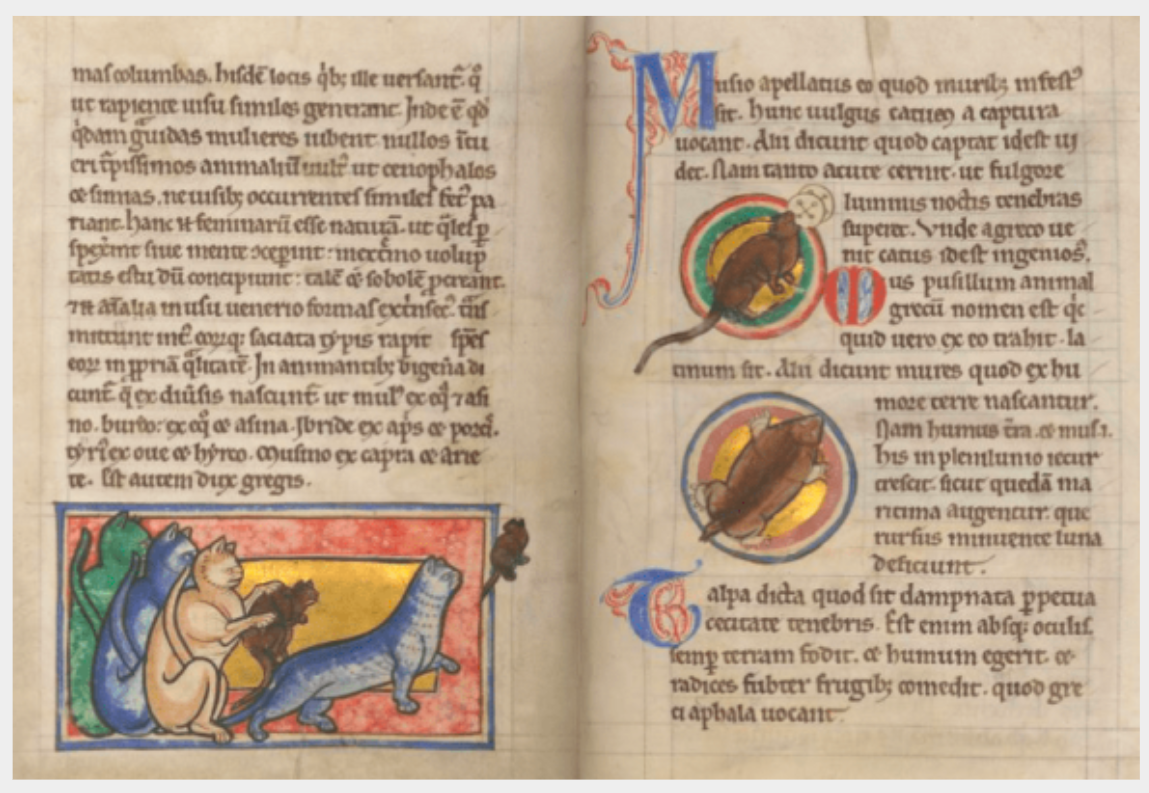

Royal 12 C xix f. 36v/37r (13th century)

Cats provided medieval citizens with the same pest control services they’d been performing since the ancient Egyptians first domesticated them.

Ancient Egyptians conveyed their gratitude and respect by regarding cats as symbols of divinity, protection, and strength.

Certain Egyptian goddesses, like Bastet, were imbued with unmistakably feline characteristics.

The Vintage News reports that harming a cat in those days was punishable by death, exporting them was illegal, and, much like today, the death of a cat was an occasion for public sorrow:

When a cat died, it was buried with honors, mummified and mourned by the humans. The body of the cat would be wrapped in the finest materials and then embalmed in order to preserve the body for a longer time. Ancient Egyptians went so far that they shaved their eyebrows as a sign of their deep sorrow for the deceased pet.

Aberdeen University Library, MS 24 f. 23v (England, c 1200)

The medieval church took a much darker view of our feline friends.

Their close ties to paganism and early religions were enough for cats to be judged guilty of witchcraft, sinful sexuality, and fraternizing with Satan.

In the late 12th-century, writer Walter Map, a soon-to-be archdeacon of Oxford, declared that the devil appeared before his devotees in feline form:

… hanging by a rope, a black cat of great size. As soon as they see this cat, the lights are turned out. They do not sing or recite hymns in a distinct way, but they mutter them with their teeth closed and they feel in the dark towards where they saw their lord], and when they find it, they kiss it, the more humbly depending on their folly, some on the paws, some under the tail, some on the genitals. And as if they have, in this way, received a license for passion, each one takes the nearest man or woman and they join themselves with the other for as long as they choose to draw out their game.

Pope Innocent VIII issued a papal bull in 1484 condemning the “devil’s favorite animal and idol of all witches” to death, along with their human companions to death.

13th-century Franciscan monk Bartholomaeus Anglicus refrained from demonic tattle, but neither did he paint cats as angels:

He is a full lecherous beast in youth, swift, pliant, and merry, and leapeth and reseth on everything that is to fore him: and is led by a straw, and playeth therewith: and is a right heavy beast in age and full sleepy, and lieth slyly in wait for mice: and is aware where they be more by smell than by sight, and hunteth and reseth on them in privy places: and when he taketh a mouse, he playeth therewith, and eateth him after the play. In time of love is hard fighting for wives, and one scratcheth and rendeth the other grievously with biting and with claws. And he maketh a ruthful noise and ghastful, when one proffereth to fight with another: and unneth is hurt when he is thrown down off an high place. And when he hath a fair skin, he is as it were proud thereof, and goeth fast about: and when his skin is burnt, then he bideth at home; and is oft for his fair skin taken of the skinner, and slain and flayed.

Pigs and rats also had a bad rep, and like cats, were tortured and executed in great numbers by pious humans.

The Worksop Bestiary Morgan Library, MS M.81 f. 47r (England, c 1185)

Not every medieval city was anti-cat. As the Academic Cat Lady Johanna Feenstra writes of the above illustration from The Worksop Bestiary, one of the earliest English bestiaries:

Some would have interpreted the image of a cat pouncing on a rodent as a symbol for the devil going after the human soul. Others might have seen the cat in a completely different light. For instance, as Eucharistic guardians, making sure rodents could not steal and eat the Eucharistic wafers.

Bodleian Library Bodley 764 f. 51r (England, c 1225–50)

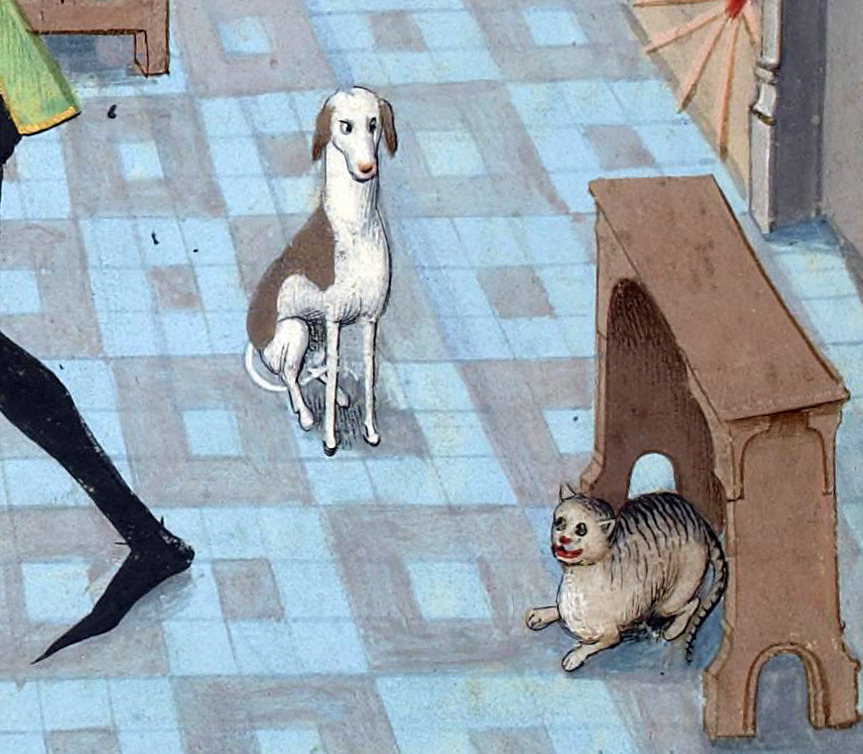

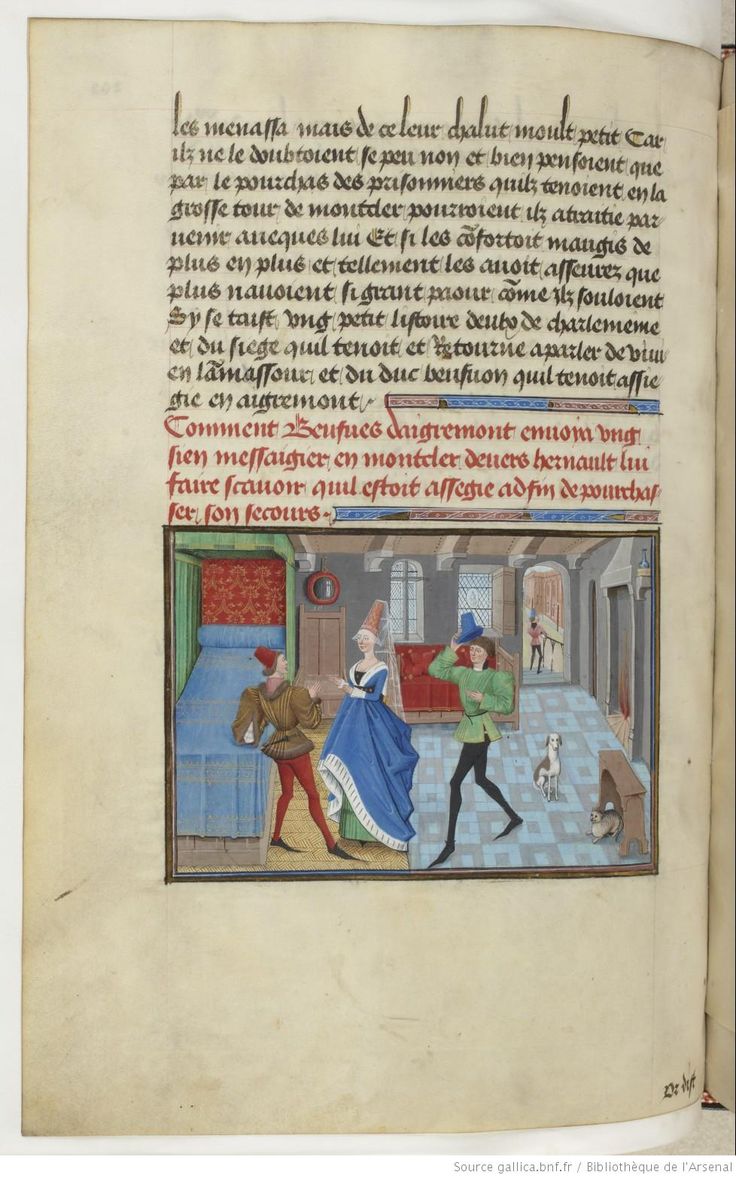

St John’s College Library, MS. 61 (England (York), 13th century)

It took cat lover Leonardo DaVinci to turn the situation around, with eleven sketches from life portraying cats in characteristic poses, much as we see them today. We’ll delve more into that in a future post.

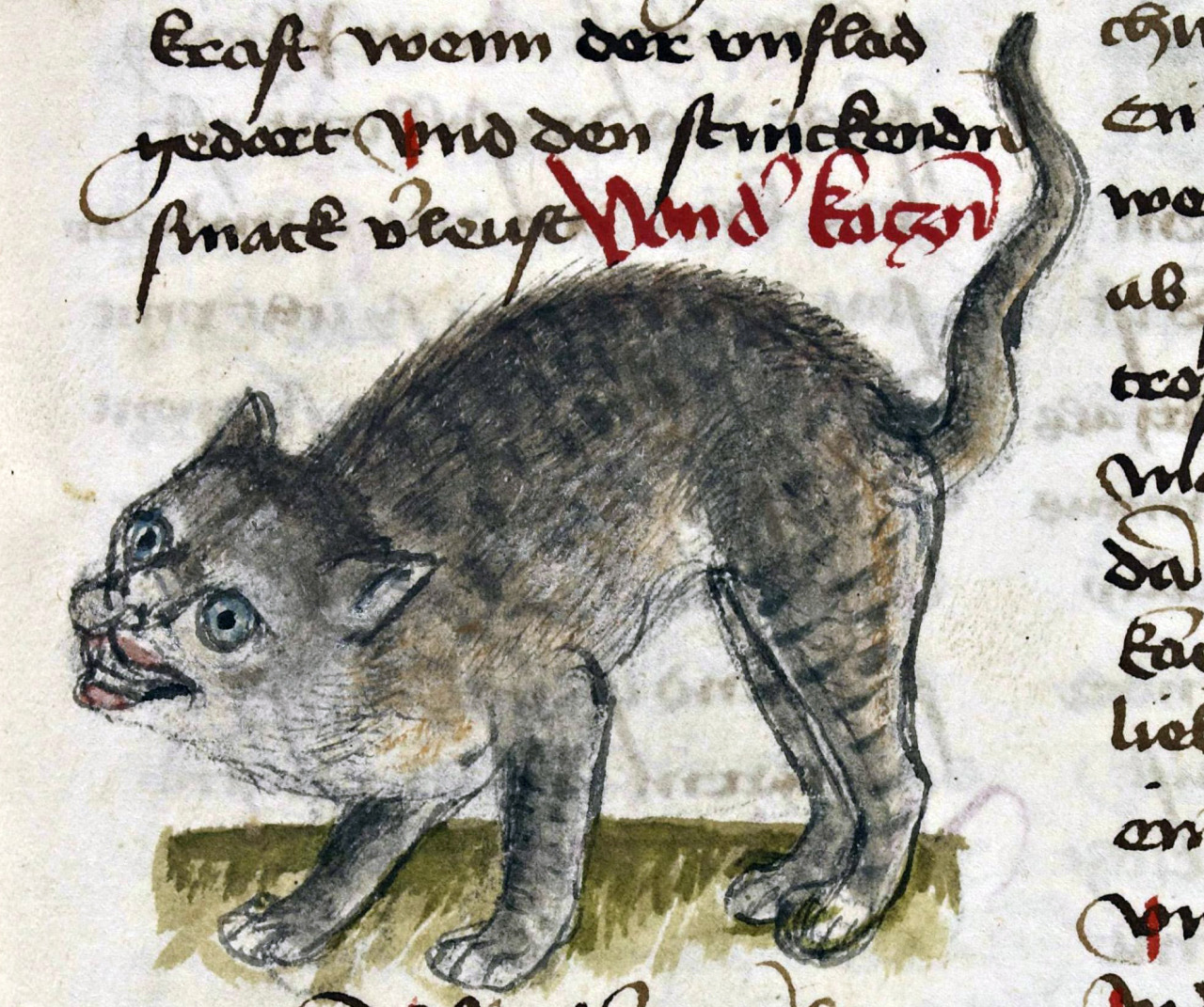

Conrad of Megenberg, ‘Das Buch der Natur’, Germany ca. 1434. Strasbourg, Bibliothèque nationale et universitaire, Ms.2.264, fol. 85r

Related Content

- Ayun Halliday is the Chief Primatologist of the East Village Inky zine and author, most recently, of Creative, Not Famous: The Small Potato Manifesto. Follow her @AyunHalliday.

I love felines so smart so independent the cat has served mankind by controlling vermin