Home baked sourdough had its moment during the early days of the pandemic, but otherwise bread has been much maligned throughout the 21st century, at least in the Western World, where carbs are vilified by body-conscious consumers.

This was hardly the case on January 18, 1943, when Americans woke up to the news that the War Foods Administration, headed by Secretary of Agriculture Claude R. Wickard, had banned the sale of sliced bread.

The reasons driving the ban were a bit murky, though by this point, Americans were well acquainted with rationing, which had already limited access to high-demand items as sugar, coffee, gasoline and tires.

Though why sliced bread, of all things?

Might depriving the public of their beloved pre-sliced bread help the war effort, by freeing up some critical resource, like steel?

Not according to The History Guy, Lance Geiger, above.

War production regulations prohibited the sale of industrial bread slicing equipment for the duration, though presumably, existing commercial bakeries wouldn’t have been in the market for more machines, just the odd repair part here and there.

Wax paper then? It kept sliced bread fresh prior to the invention of plastic bags. Perhaps the Allies had need of it?

No, unlike nylon, there were no shortages of waxed paper.

Flour had been strictly regulated in Great Britain during the first World War, but this wasn’t a problem stateside in WWII, where it remained relatively cheap and easy to procure, with plenty leftover to supply overseas troops. 1942’s wheat crop had been the second largest on record.

There were other rationales having to do with eliminating food waste and relieving economic pressure for bakers, but none of these held up upon examination. This left the War Production Office, the War Price Administration, and the Office of Agriculture vying to place blame for the ban on each other, and in some cases, the American baking industry itself!

While the ill considered ban lasted just two months, the public uproar was considerable.

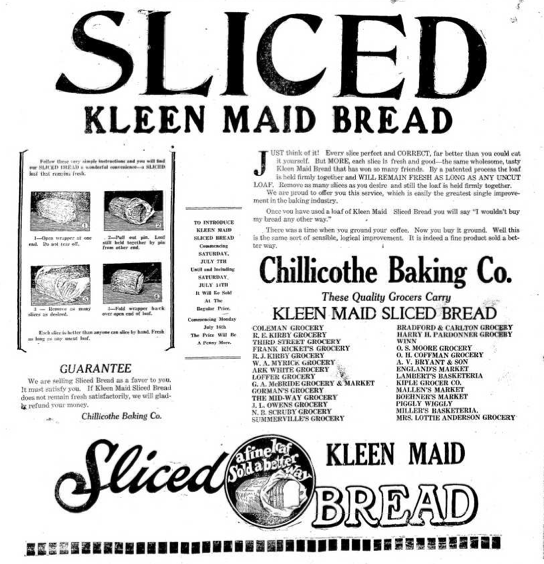

Although pre-sliced bread hadn’t been around all that long, in the thirteen-and-a-half years since its introduction, consumers had grown quite dependent on its convenience, and how nicely those uniform slices fit into the slots of their pop up toasters, another recently-patented invention.

A great pleasure of the History Guy’s coverage is the name checking of local newspapers covering the Sliced Bread Ban:

An absence of data did not prevent a reporter for the Wilmington News Journal from speculating that “it is believed that the majority of American housewives are not proficient bread slicers.”

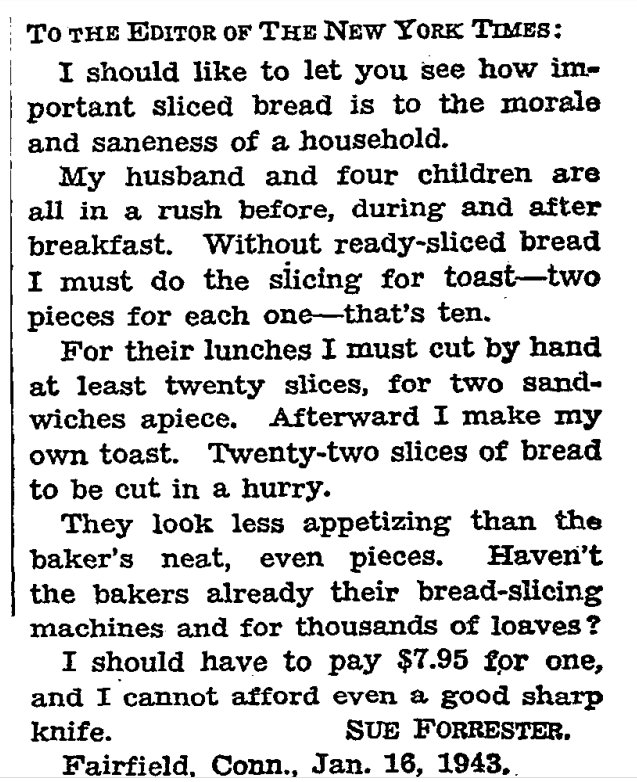

One such housewife, having spent a hectic morning hacking a loaf into toast and sandwiches for her husband and children, wrote a letter to the New York Times, passionately declaring “how important sliced bread is to the morale and saneness of a household.”

The more stiff upper lipped patriotism of Vermont home economics instructor Doris H. Steele found a platform in the Barre Times:

In Grandmother’s day, the loaf of bread had a regular place at the family table. Grandmother had an attractive board for the bread to stand on and a good sharp knife alongside. Grandmother knew that a steady hand and a sharp knife were the secrets of slicing bread. She sliced as the family asked for bread and in this way, she didn’t waste any bread by cutting more than the family could eat. Let’s all contribute to the war effort by slicing our own bread.

Then, as now, celebrities felt compelled to weigh in.

New York City Mayor Fiorello LaGuardia found it ludicrous that bakeries should be prevented from putting their existing equipment to use.

And Hollywood actress Olivia de Havilland approved of the ban on the grounds that packaged slices were too thick.

Watch more of the History Guy’s videos here.

Related Content

How to Bake Ancient Roman Bread Dating Back to 79 AD: A Video Primer

See Ridley Scott’s 1973 Bread Commercial—Voted England’s Favorite Advertisement of All Time

Take a Virtual Tour of the World’s Only Sourdough Library

- Ayun Halliday is the Chief Primatologist of the East Village Inky zine and author, most recently, of Creative, Not Famous: The Small Potato Manifesto. Follow her @AyunHalliday.

Leave a Reply