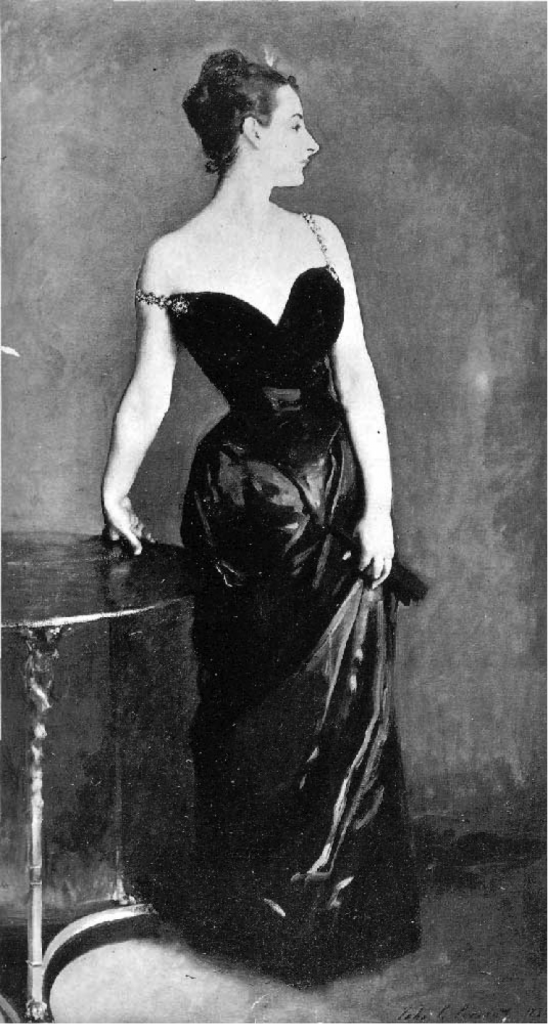

Anyone who’s ever walked the red carpet or posed for a high fashion shoot would count themselves lucky to create the sort of impression made by John Singer Sargent’s iconic portrait of Madame X.

Though not if we’re talking about the sort of impression the painting made in 1884, when the model’s haughty demeanor, plunging bodice, and unapologetic use of skin-lightening, possibly arsenic-based cosmetics got the Paris Salon all riled up.

Most scandalously, one of her gown’s jeweled straps had slipped from her shoulder, a costume malfunction this cool beauty apparently couldn’t be bothered to fix, or even turn her head to acknowledge.

Virginie Amélie Avegno Gautreau, the New Orleans-born Paris socialite (social climber, some would have sniffed) so strikingly depicted by Sargent, was horrified by her likeness’ reception at the Salon. Although Sargent had coyly replaced her name with an ellipses in the painting’s title, there was no doubt in viewers’ minds as to her identity.

John Sargent, Evan Charteris’ 1927 biography, shows Madame Gautreau very little mercy when recounting her attempts at damage control:

A demand was made that the picture should be withdrawn. It is not among the least of the curiosities of human nature, that while an individual will confess and even draw attention to his own failings, he will deeply resent the same office being undertaken by someone else. So it was with the dress of Madame Gautreau. Here a distinguished artist was proclaiming to the public in paint a fact about herself she had hitherto never made any attempt to conceal, one which had, indeed, formed one of her many social assets. Her resentment was profound.

Sargent, distraught that his portrait of the celebrated scenemaker had yielded the opposite of the hoped-for positive splash, refused to indulge her request to remove the painting from exhibition.

His friend, painter Ralph Wormeley Curtis, wrote to his parents of the scene he witnessed in Sargent’s studio when Madame Gautreau’s mother rolled up, “bathed in tears”, primed to defend her daughter:

(She) made a fearful scene saying “Ma fille est perdu — tout Paris se moque d’elle. Mon genre sera forcé de se battre. Elle mourira de chagrin” etc.

(My daughter is lost — all of Paris mocks her. My kind will be forced to fight. She will die of sorrow.)

John replied it was against all laws to retire a picture. He painted her exactly as she was dressed, that nothing could be said of the canvas than had been said of her appearance dans le monde etc. etc.

Defending his cause made him feel much better. Still we talked it all over till 1 o’clock here last night and I fear he has never had such a blow. He says he wants to get out of Paris for a time. He goes to Eng. in 3 weeks. I fear là bas he will fall into Pre‑R. Influence wh. has got a strange hold of him, he says since Siena.

As Charlotte, creator of the Art Deco YouTube channel, points out in a frenetic overview of the scandal, below, Sargent came out of this fiasco a bit better than Madame Gautreau, whose damaged reputation cost her friends as well as her queen bee status.

(In her essay, Virginie Amélie Avegno Gautreau: Living Statue, art historian Elizabeth L. Block corrects Charlotte’s assertion that the painting “destroyed Madame Gautreau’ life”. Contrary to popular opinion, within three years, she was making her theatrical debut, hosting parties, and was hailed by the New York Times as a “piece of plastic perfection.”)

Sargent did indeed decamp for England, where he found both creative and critical success. By century’s end, he was widely recognized as the most successful portrait painter of his day.

The portrait of Madame Gautreau remained enough of a sore spot that he kept it out of the public eye for more than twenty years, though shortly after its disastrous debut at the Salon, he did take another swipe at it, repositioning the suggestive shoulder strap to a more conventionally acceptable location, as the below photo, taken in his studio in 1885 confirms.

In 1905, he finally allowed it to see the light of day in a London exhibition, with subsequent engagements in Berlin, Rome and San Francisco.

In 1916, when the portrait was still on display in San Francisco, he wrote his friend Edward “Ned” Robinson, Director of The Metropolitan Museum of Art, offering to sell it for £1,000, saying, “I suppose it is the best thing I have done.”

“By the way,” he added, “I should prefer, on account of the row I had with the lady years ago, that the picture should not be called by her name.”

Even though Madame Gautreau had died the previous year, Robinson obliged, retitling the painting Portrait of Madame X, the name by which it and its glamorous model are famously known today.

Read Elizabeth L. Block’s fascinating essay, “Virginie Amélie Avegno Gautreau: Living Statue” here.

Read about the discoveries Metropolitan Museum of Art conservationists made during X‑radiography and infrared reflectography of the portrait here.

Completionists might even want to have a gander at Nicole Kidman done up to resemble Madame X for a 1998 Vogue spread shot by Steven Meisel.

Related Content

When Pablo Picasso and Guillaume Apollinaire Were Accused of Stealing the Mona Lisa (1911)

- Ayun Halliday is the Chief Primatologist of the East Village Inky zine and author, most recently, of Creative, Not Famous: The Small Potato Manifesto. Follow her @AyunHalliday.

Leave a Reply