Do you swoon at the sight of blood?

Suffer paper cuts as major trauma?

Cover your eyes when the knife comes out in the horror movie?

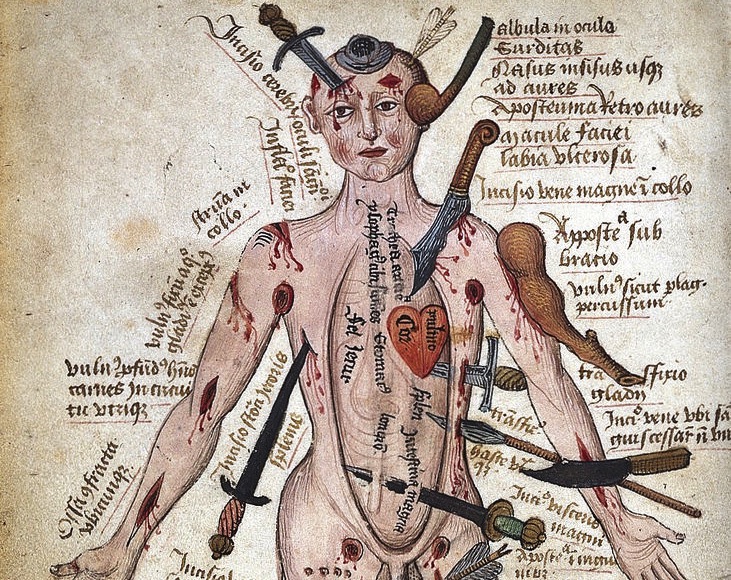

If so, and also if not, fall to your knees and give thanks that you’re not the Wound Man, above.

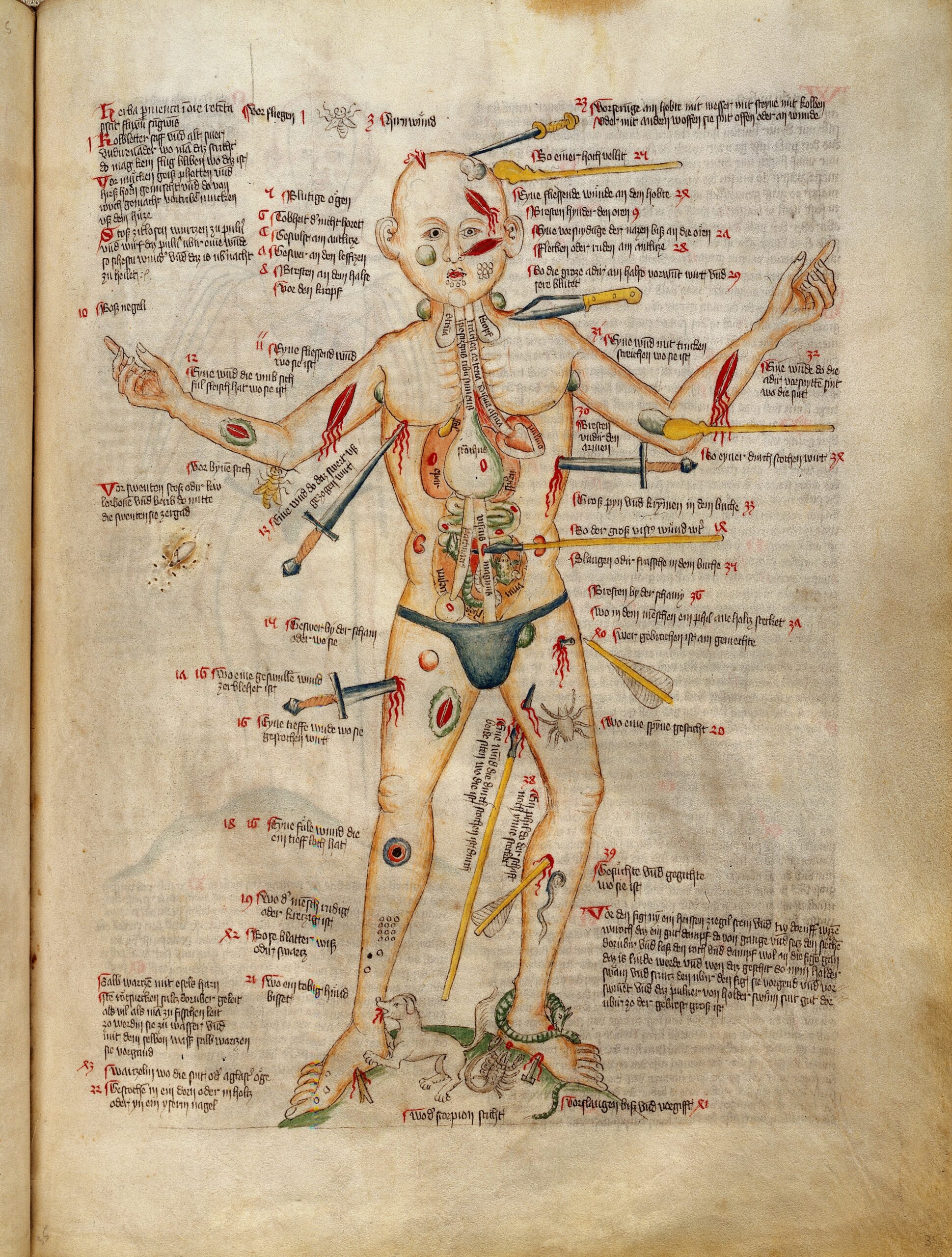

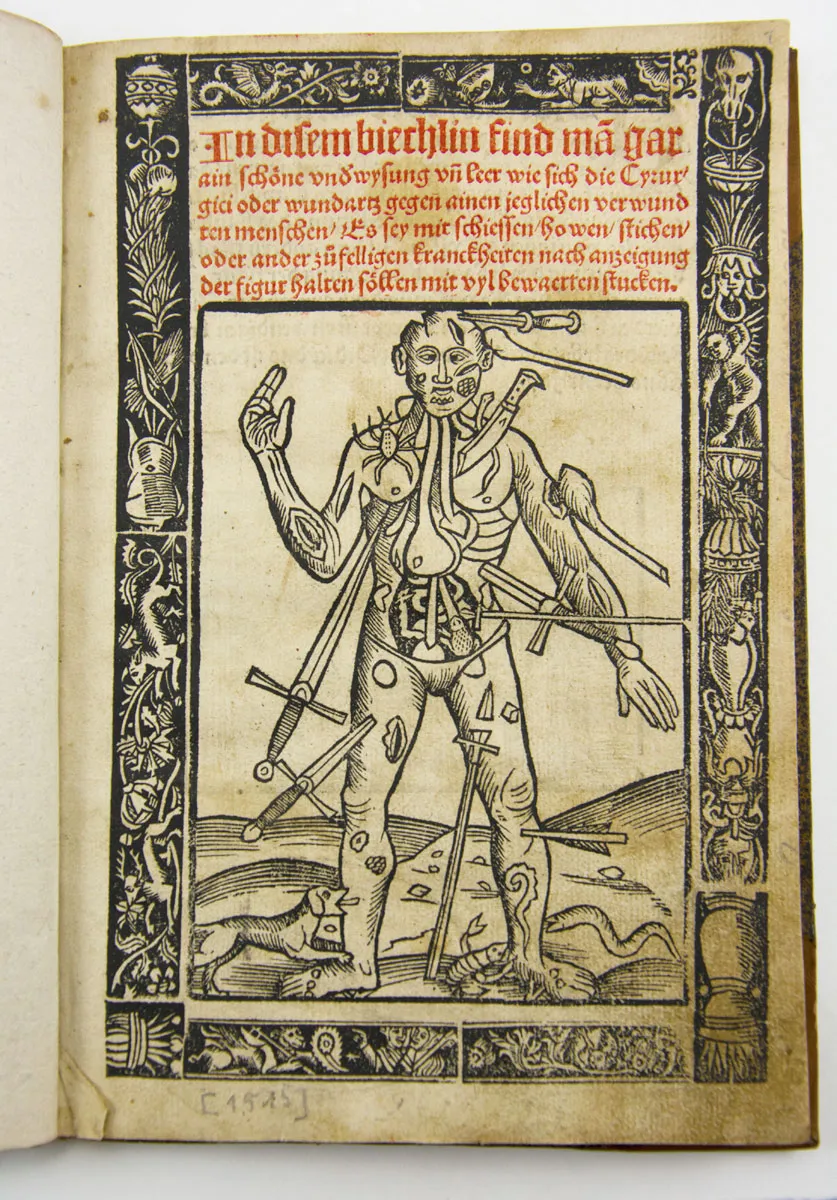

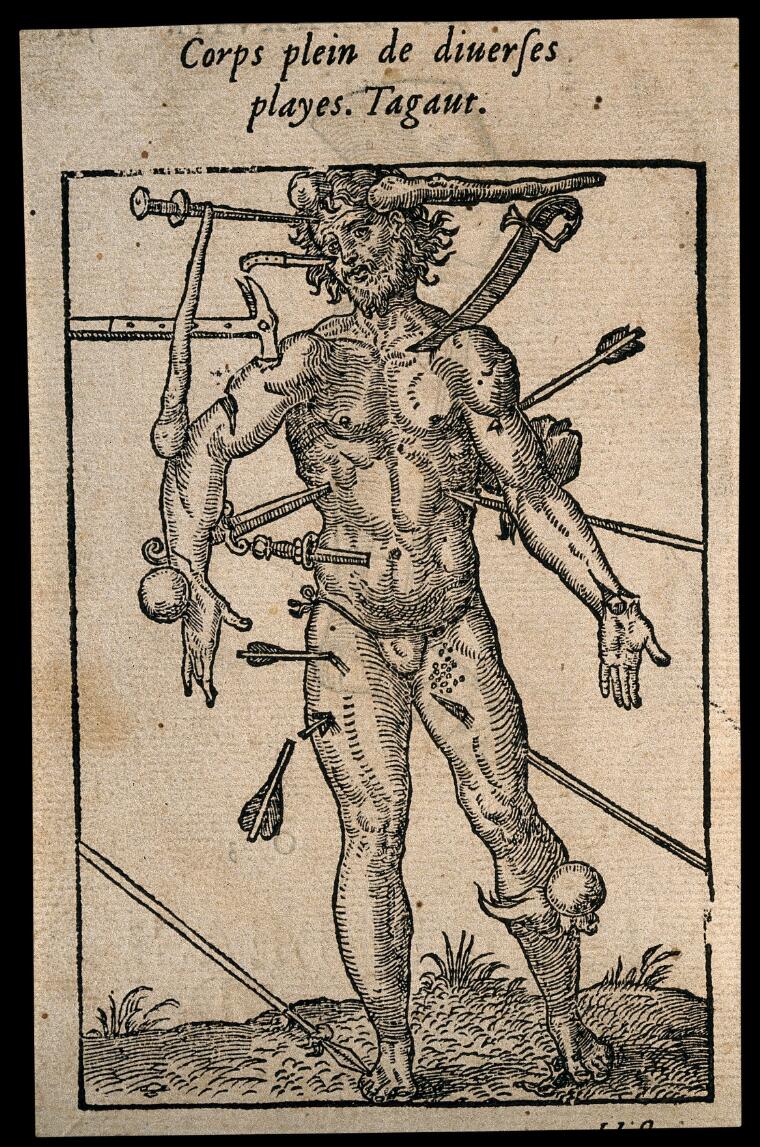

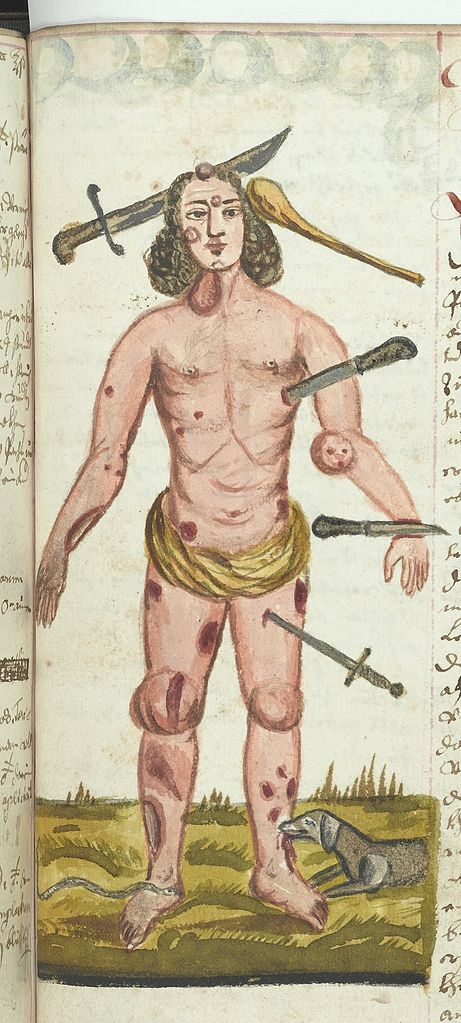

A staple of medieval medical history, he’s a grisly compendium of the injuries and external afflictions that might befall a mortal of the period- insect and animal bites, spilled entrails, abscesses, boils, infections, plague-swollen glands, piercings and cuts, both accidental and deliberately inflicted.

Any one of these troubles should be enough to fell him, yet he remains upright, displaying every last one of them simultaneously, his expression stoic.

He’s hard to look at, but as art historian Jack Hartnell , author of Medieval Bodies: Life, Death and Art in the Middle Ages writes in British Art Studies:

The Wound Man was not a figure designed to inspire fear or to menace. On the contrary, he represented something more hopeful: an imaginative and arresting herald of the powerful knowledge that could be channelled and dispensed through the practice of medieval medicine.

A valuable educational resource for surgeons for some three centuries, he began cropping up in southern Germany in the early 1400s. In an essay for the Public Domain Review, Hartnell notes how these early specimens served “as a human table of contents”, directing interested parties to the specific passages in the various medical texts where information on existing treatments could be found.

The protocol for injuries to the intestines or stomach called for stitching the wound up with a fine thread and sprinkling it with an antihemorrhagic powder made from wine, hematite, nutmeg, white frankincense, gum arabic, bright red sap from the Dracaena cinnabari tree and a restorative quantity of mummy.

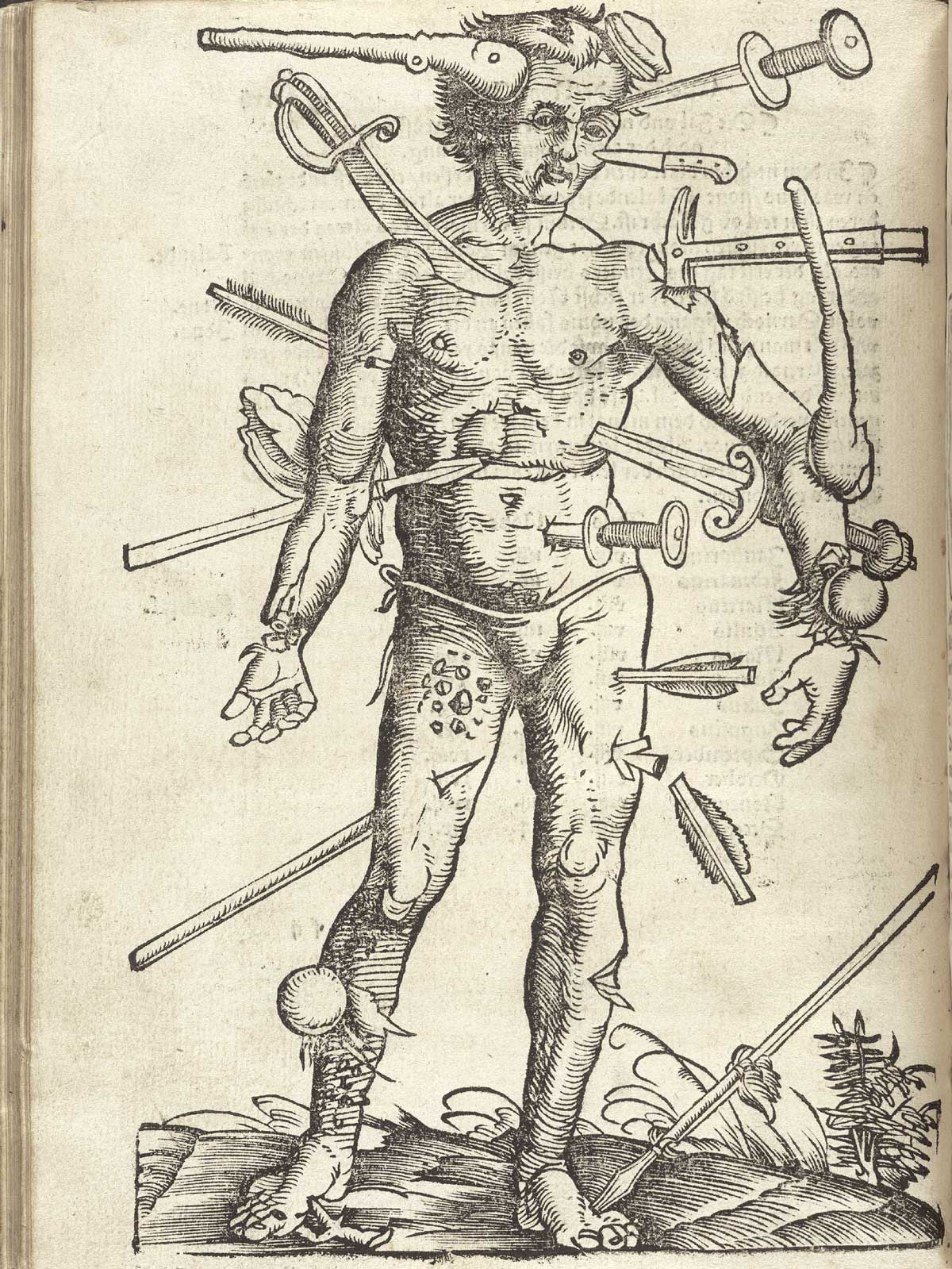

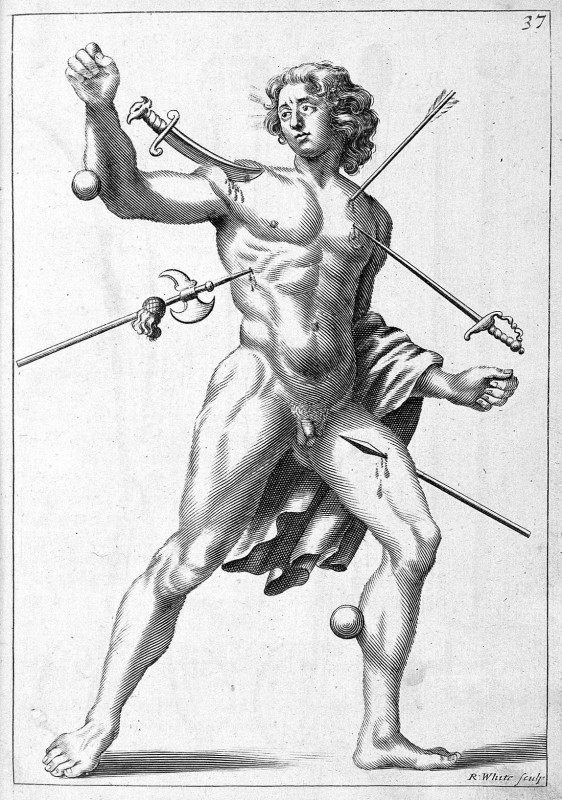

The Wound Man evolved along with medical knowledge, weapons of warfare and art world trends.

The woodcut Wound Man in Hans von Gersdorff’s 1517 landmark Fieldbook of Surgery introduces cannonballs to the ghastly mix.

And the engraver Robert White’s Wound Man in British surgeon John Browne’s 1678 Compleat Discourse of Wounds loses the loincloth and grows his hair, morphing into a neoclassical beauty in the Saint Sebastian mold.

Surgical knowledge eventually outpaced the Wound Man’s usefulness, but popular culture is far from ready for him to lay down and die, as evidenced by recent cameos in episodes of Hannibal and the British comedy quiz show, QI.

Delve into the history of the Wound Man in Jack Hartnell’s British Art Studies article “Wording the Wound Man.”

Related Content

1,000-Year-Old Illustrated Guide to the Medicinal Use of Plants Now Digitized & Put Online

- Ayun Halliday is the Chief Primatologist of the East Village Inky zine and author, most recently, of Creative, Not Famous: The Small Potato Manifesto. Follow her @AyunHalliday.

Leave a Reply