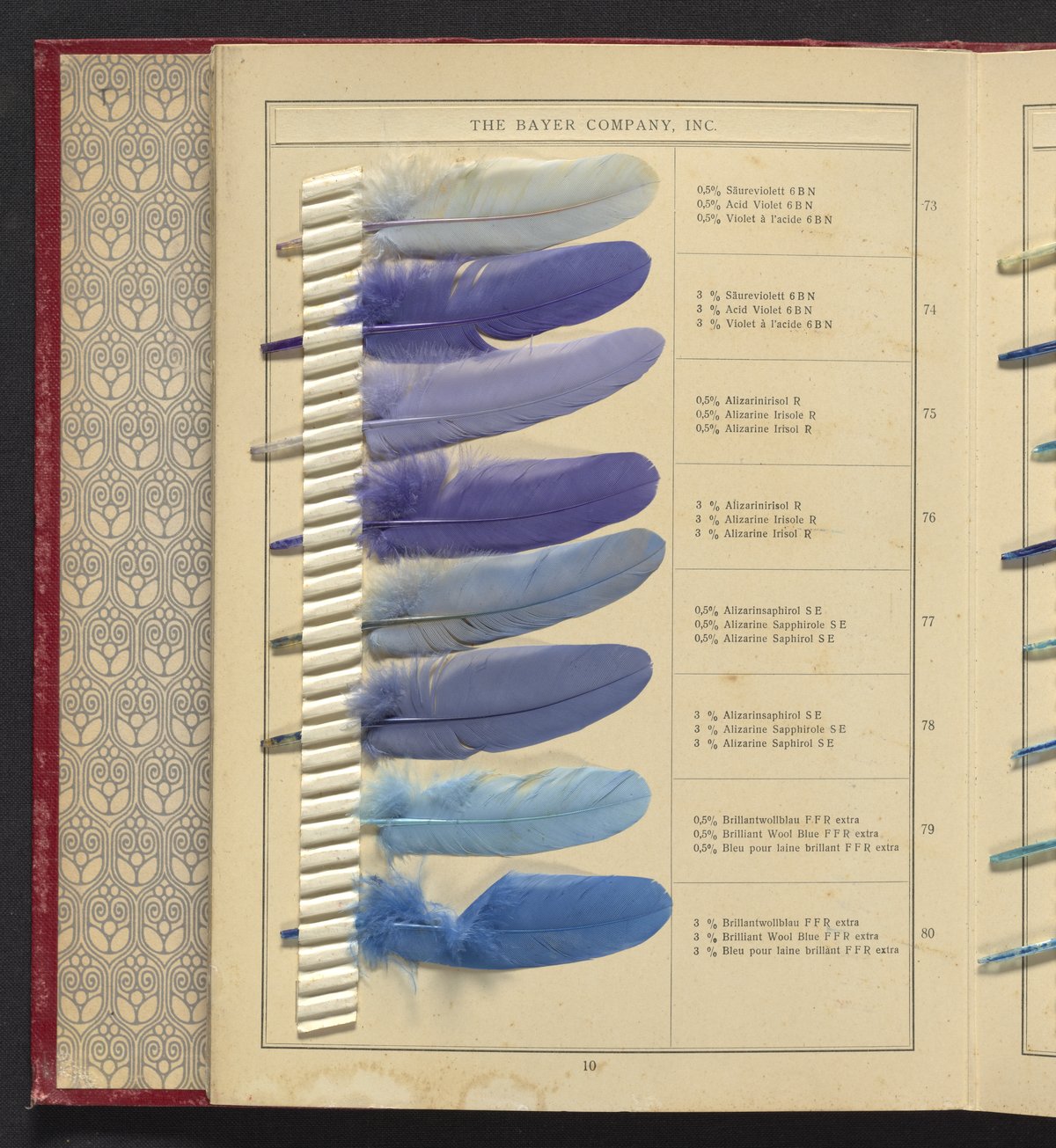

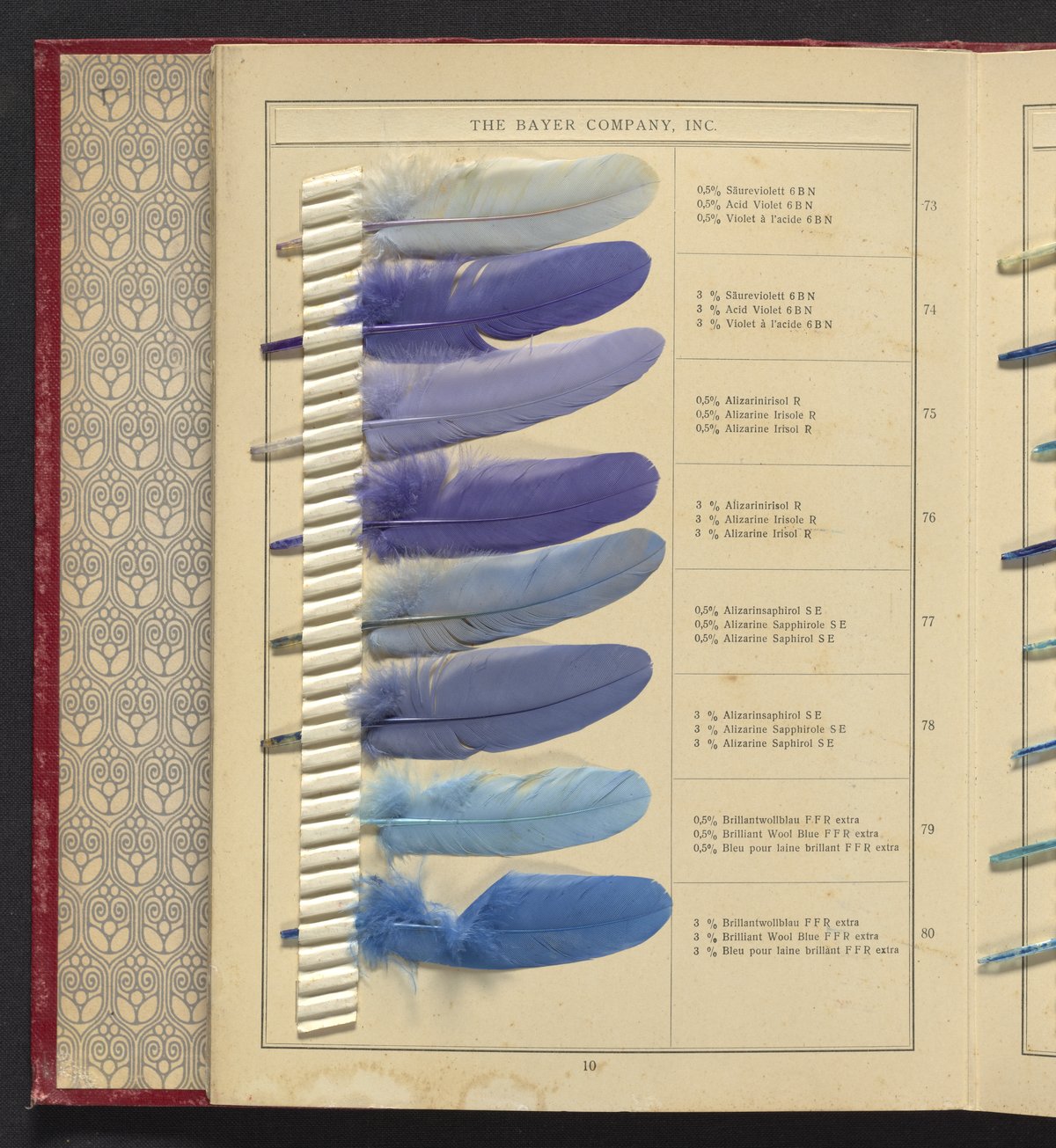

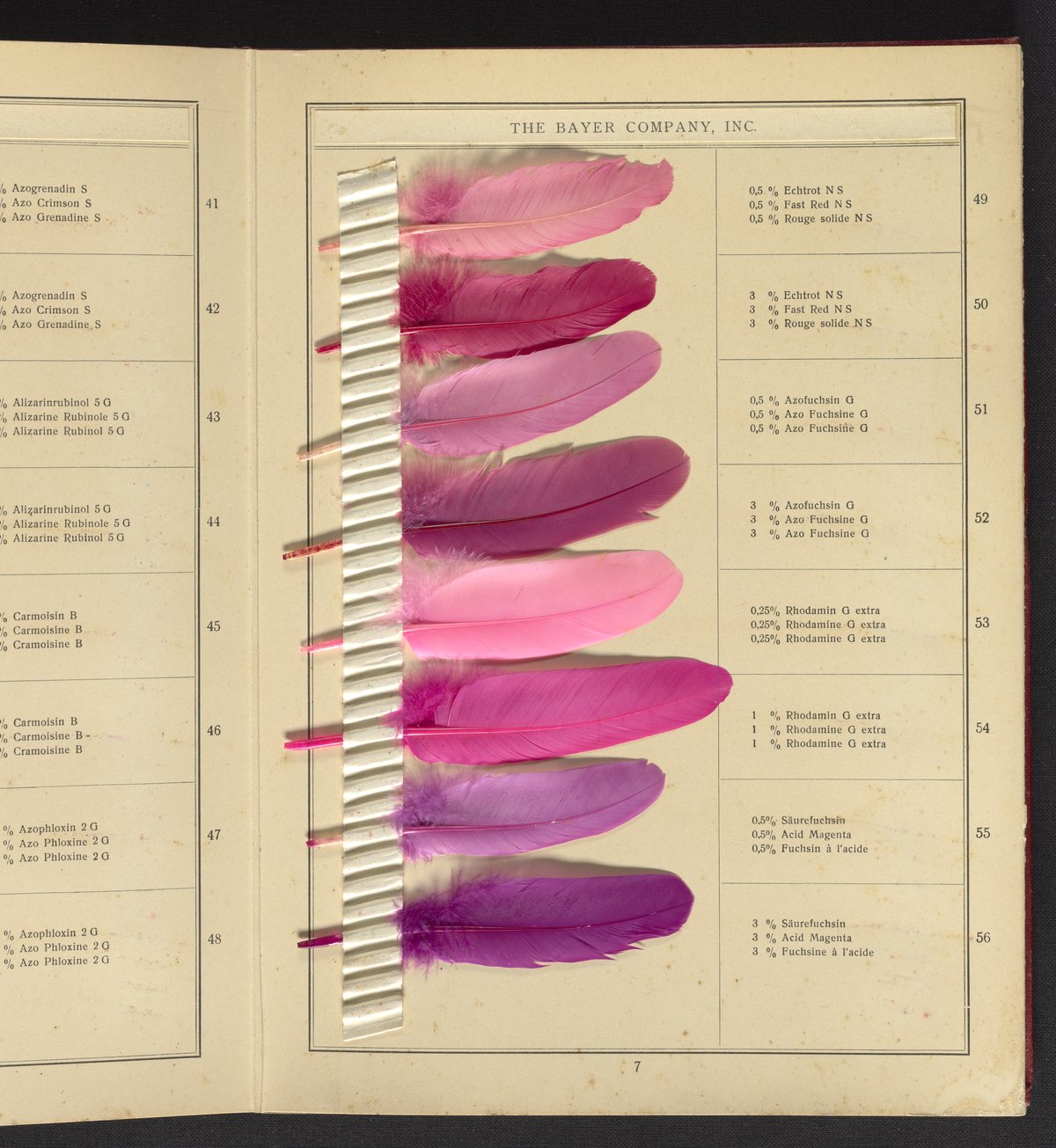

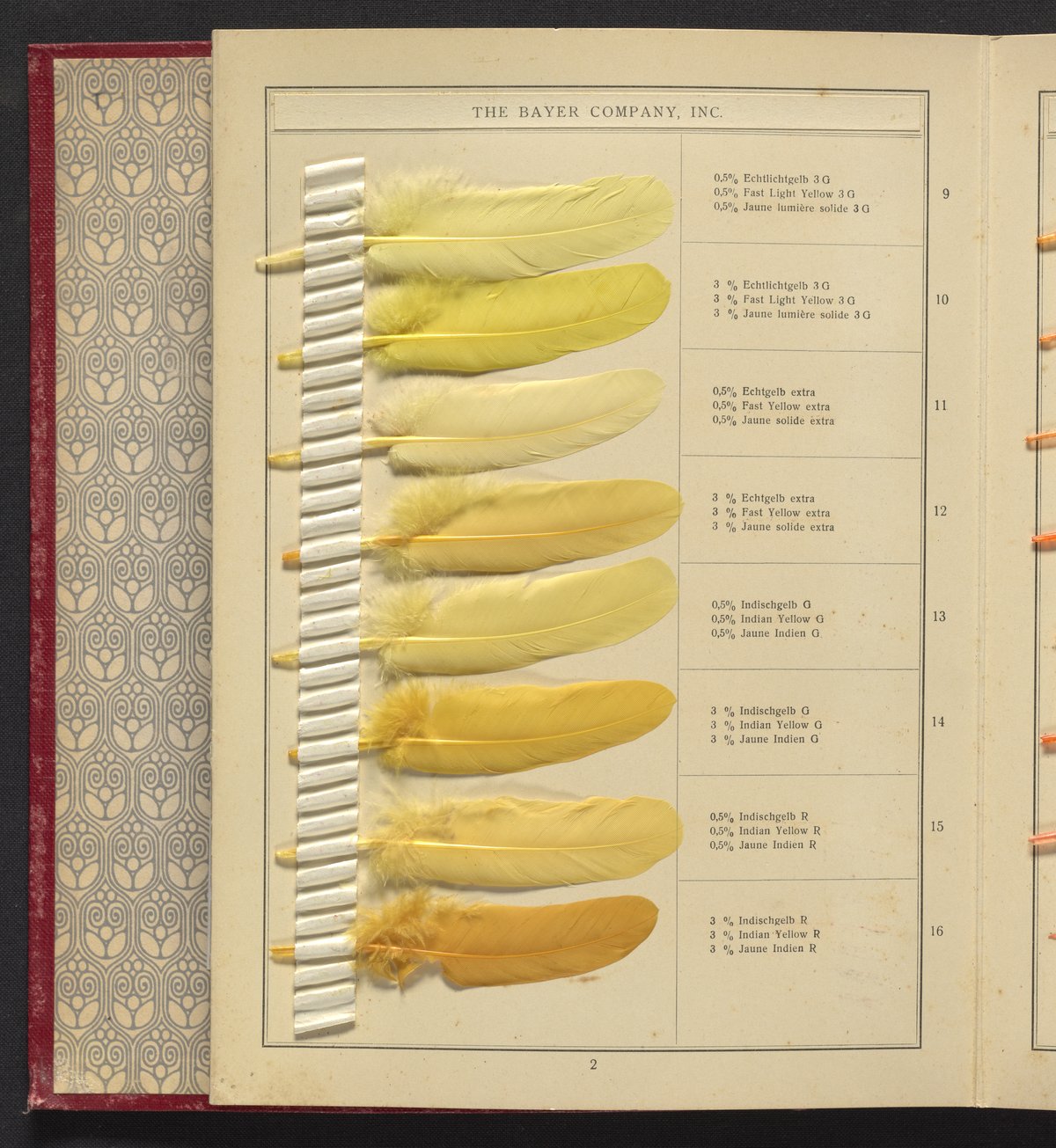

Perhaps the 143 colors showcased in The Bayer Company’s early 20th-century sample book, Shades on Feathers, could be collected in the field, but it would involve a lot of travel and patience, and the stalking of several endangered if not downright extinct avian species.

Far easier, and much less expensive, for milliners, designers and decorators to dye plain white feathers exotic shades, following the instructions in the sample book.

Such artificially obtained rainbows owe a lot to William Henry Perkin, a teenage student of German chemist August Wilhelm von Hofmann, who spent Easter vacation of 1856 experimenting with aniline, an organic base his teacher had earlier discovered in coal tar. Hoping to hit on a synthetic form of quinine, he accidentally hit on a solution that colored silk a lovely purple shade — an inadvertent eureka moment that ranks right up there with penicillin and the pretzel.

A Science Museum Group profile details what happened next:

Perkin named the colour mauve and the dye mauveine. He decided to try to market his discovery instead of returning to college.

On 26 August 1856, the Patent Office granted Perkin a patent for ‘a new colouring matter for dyeing with a lilac or purple colour stuffs of silk, cotton, wool, or other materials’.

Perkin’s next step was to interest cloth dyers and printers in his discovery. He had no experience of the textile trade and little knowledge of large-scale chemical manufacture. He corresponded with Robert and John Pullar in Glasgow, who offered him support. Perkin’s luck changed towards the end of 1857 when the Empress Eugénie, wife of Napoleon III, decided that mauve was the colour to wear. In January 1858, Queen Victoria followed suit, wearing mauve to her daughter’s wedding.

Cue an explosion of dye manufacturers across Great Britain and Europe, including Bayer, producer of the feather sample book. The survival of this artifact is somewhat miraculous given how vulnerable antique feathers are to environmental factors, pests, and improper storage.

(The sample book recommends cleaning the feathers prior to dying in a lukewarm solution of small amounts of olive oil soap and ammonia.)

The Science History Institute, owner of this unusual object, estimates that the undated book was produced between 1913 and 1918, the year the Migratory Bird Act Treaty outlawed the hunting of birds whose feathers humans deemed particularly fashionable.

Peruse the Science History Institute of Philadelphia’s digitized copy of the Shades on Feathers sample book here.

Related Content

Download 435 High Resolution Images from John J. Audubon’s The Birds of America

The Bird Library: A Library Built Especially for Our Fine Feathered Friends

- Ayun Halliday is the Chief Primatologist of the East Village Inky zine and author, most recently, of Creative, Not Famous: The Small Potato Manifesto. Follow her @AyunHalliday.

Leave a Reply