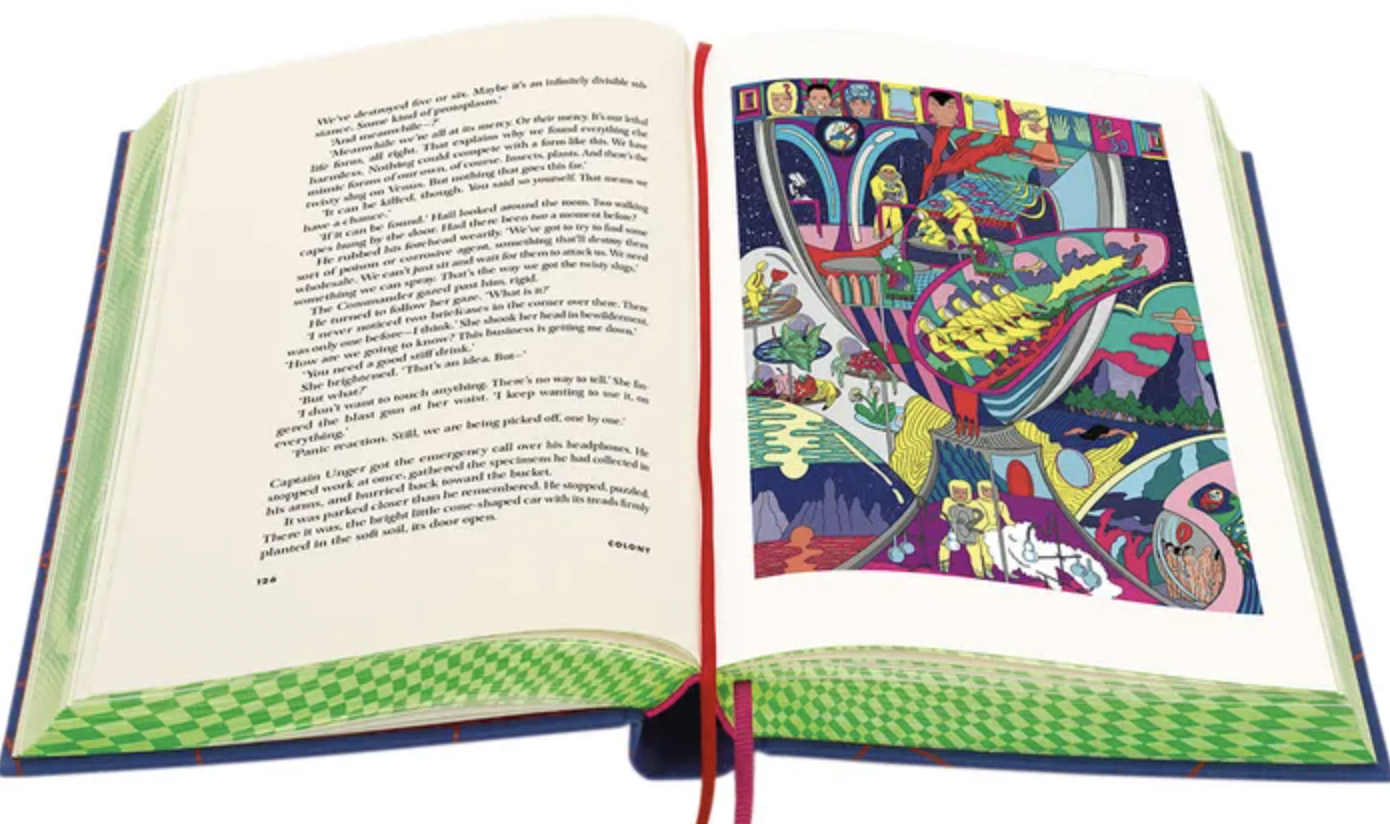

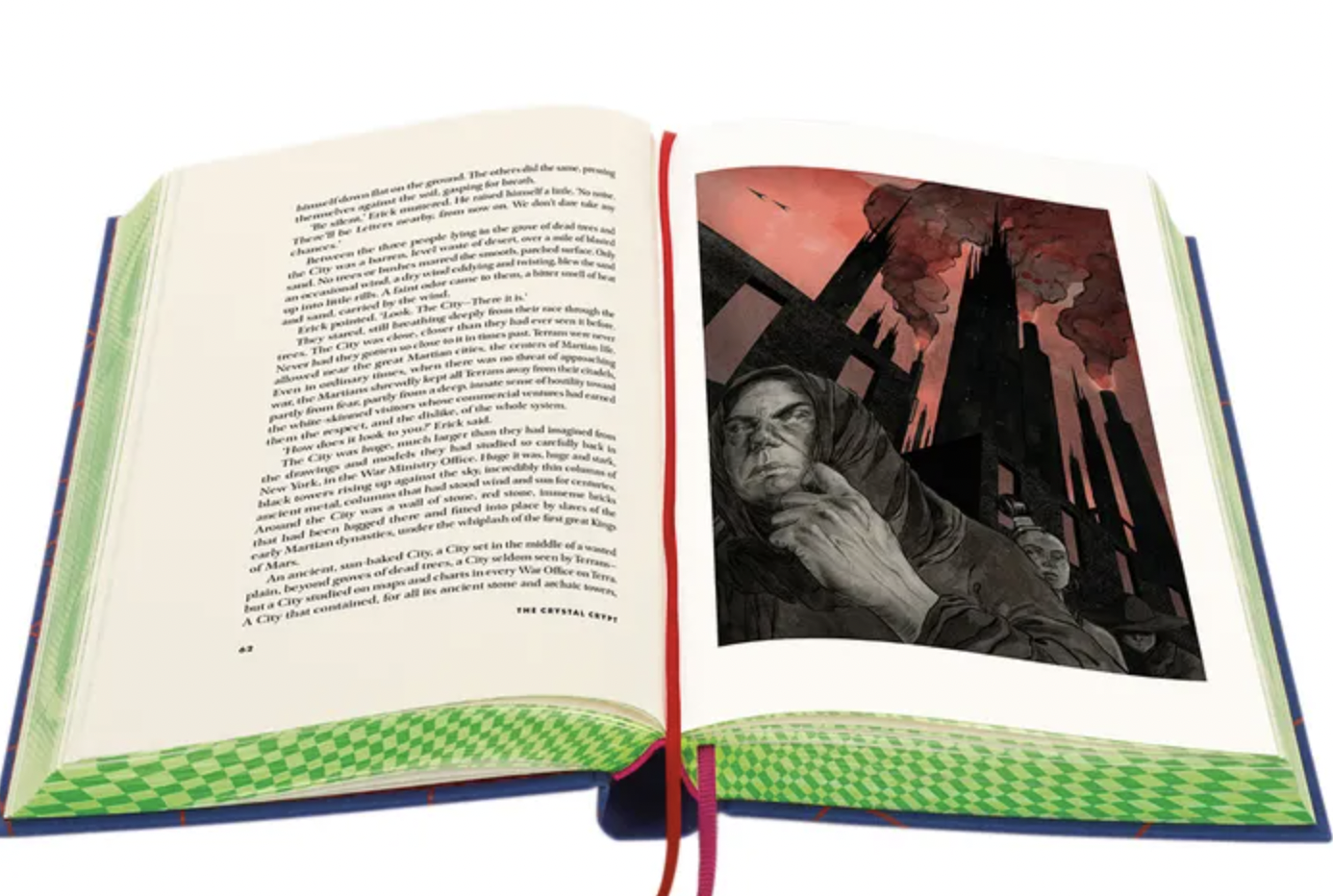

Philip K. Dick’s multiple worlds have appeared in increasingly better editions since the author passed away in 1982. In the 21st century, respectable hardbacks and quality paper have fully replaced yellowed, pulpy pages. Maybe no edition yet is more attractive than the Folio Society of London’s two-volume hardback set of Dick’s selected short stories, illustrated by 24 different artists and including tales that have survived film adaptations, for better and worse, like “Paycheck,” “The Minority Report,” and “We Can Remember It for You Wholesale.” The books will set you back $125, but that’s a small sum compared to the price of an earlier, four-volume Complete Short Stories, published in a limited edition of 750, day-glo, hand-numbered copies. These sold out in less than 48 hours and now go for $2,500 in rare online sales.

In death Dick has achieved what he sought in his writing life: success as literary author. He thought he would eventually publish his realist fiction to earn the reputation, vowing in 1960 that he would “take twenty to thirty years to succeed as a literary writer.” Instead, he’s famous for great fiction that just happens to use the idiom of sci-fi to ask, as he wrote in an undelivered 1978 speech: “What is reality?” and “What constitutes an authentic human being?”

We tend to associate these existential, pre-post-modernist questions with novels and novellas from the 60s and 70s that communicate Dick’s paranoid worldview — works nominated for a Nebula Award, for example, like Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep?, the source for the best of the film adaptations, Blade Runner.

Dick first won fame in 1963 when he was given the Hugo Award for The Man in the High Castle, a book that exceeds the boundaries of genre to become, unmistakably, a PKD original. His earlier stories, on the other hand, written throughout the 1950s when the author was in his twenties, tend to follow the conventions of the hard sci-fi of the time, with the same themes of space travel, robotics, and other futuristic technology that predominate in Robert Heinlein and Isaac Asimov. Superficially, there might seem little to distinguish Dick’s early stories from other writing of the time published in pulps like Science Fiction Quarterly, Galaxy Science Fiction, and IF.

But the early stories show the unmistakable touch of the later novelist. There are the flashes of humor, absurdity, deep insight into the human psyche, and the warmth and empathy Dick’s narrative voice never lost even in his most bizarre fugues. In his first published story, “Roog,” sold in 1951, Dick imagines a dog who believes the garbage men come to steal the family’s food, leaving only the empty metal storage can behind. “Certainly, I decided,” he writes, “that dog sees the world quite differently than I do, or any humans. And then I began to think, maybe each human being lives in a unique world, a private world, a world different from those inhabited and experienced by all other humans.”

It’s a short leap from these thoughts to the idea that there might be no singular reality at all to fight over. Back then, he says, “I had no idea that such fundamental issues could be pursued in the science fiction field. I began to pursue them unconsciously.” His unconscious led him, in 1954’s “Adjustment Team” — the source of a less-than-great film — to imagine another dog, one who talks and interferes in human affairs (a detail omitted, thankfully, from The Adjustment Bureau). Dick’s early stories often featured comical animals — such as the Okja-like Martian pig in “Beyond Likes the Wub,” a highly-intelligent creature capable of telepathy and deep feeling. While he would turn his attention from animals and aliens to androids, alternate realities, and altered states of consciousness, Dick always had the ability to turn the genre of science fiction into a literary tool for the most daring of philosophical investigations.

Learn more about the two-volume Folio Society Selected Stories of Philip K. Dick here.

Related Content:

33 Sci-Fi Stories by Philip K. Dick as Free Audio Books & Free eBooks

Hear 6 Classic Philip K. Dick Stories Adapted as Vintage Radio Plays

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

Leave a Reply