“I shall only say that those ladies who study the rules of the art, secure a never-ceasing source of pleasure to themselves, which is always at their own command.… while those who pursue the practical part alone, can make no progress whenever their teacher or copy is withdrawn.”

The history of color theory is a story we tell based on available facts. Like many histories, it has mostly been a story by and about men. Isaac Newton’s experiments with optics inspired the broader inquiry. Johann Wolfgang von Goethe’s 1810 Theory of Colors set a standard — visually and philosophically — for books about color in the following centuries. A series of lesser-known names surround them, to the founders of color monopolist Pantone and beyond.

Maybe the story would be different if Mary Gartside’s work had been more readily available to her contemporaries and successors. Gartside, an English watercolor teacher and painter of botanical subjects, published An Essay on Light and Shade in 1805, and an expanded edition, An Essay on a New Theory of Colours in 1808. The obscure study constitutes “one of the rarest and most unusual books about color ever published,” says Alexandra Loske, curator at Brighton’s Royal Pavilion and herself a historian of color.

Loske found that Gartside is “one of the only nineteenth-century women to have composed ‘theoretical treatises on colour,’ ” as Public Domain Review writes, “nearly a century before Emily Noyes Vanderpoel published her Color Problems (1902).”

Gartside wrote in conversation with Newton and in critique of “eighteenth-century theories proposed by Gerard de Lairesse and William Herschel.” Gartside’s book anticipates Goethe and James Sowerby’s 1809 A New Elucidation of Colours and draws “parallel conclusions” about “the eye of the beholder as the centre and origin of colour perception.”

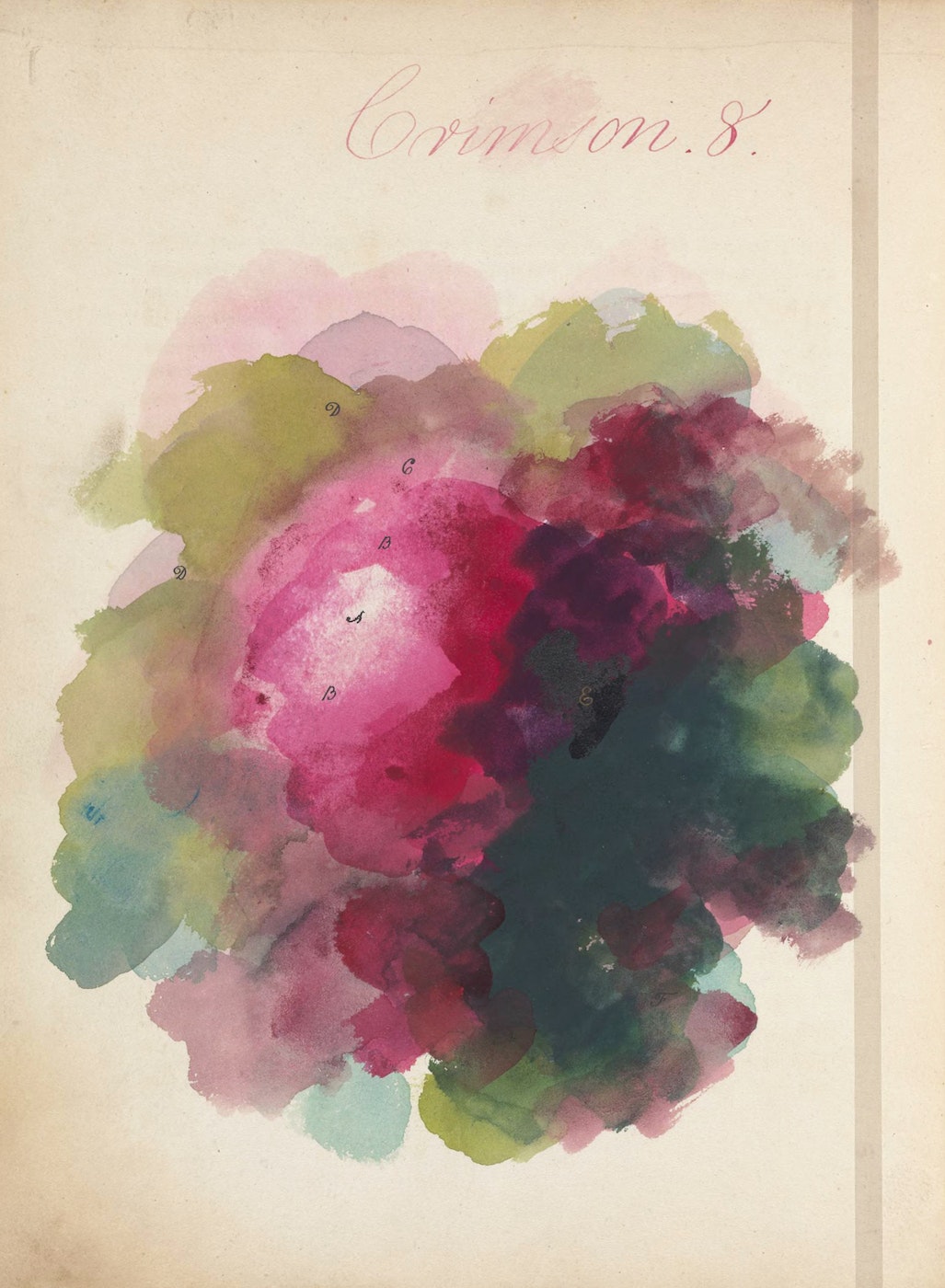

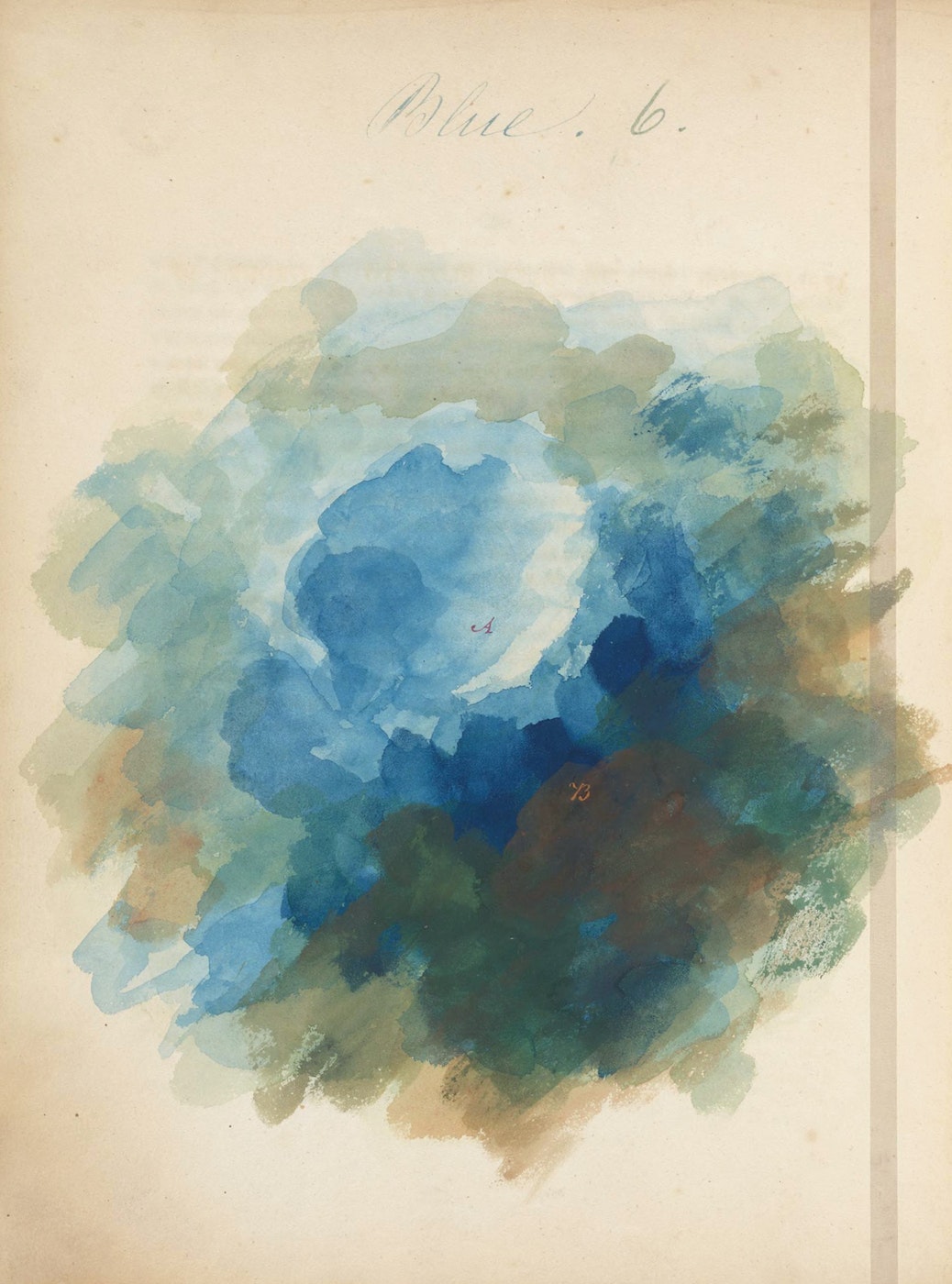

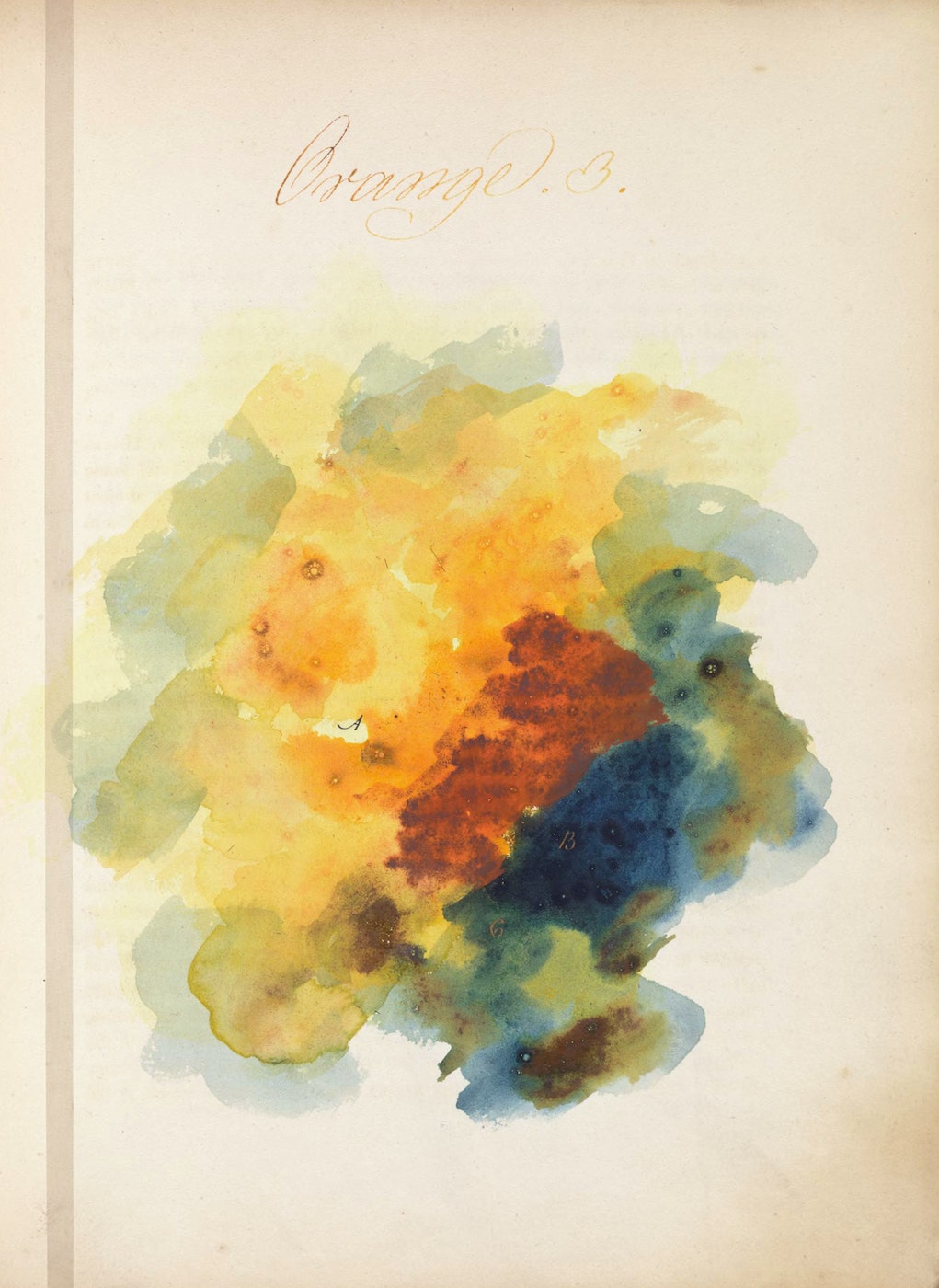

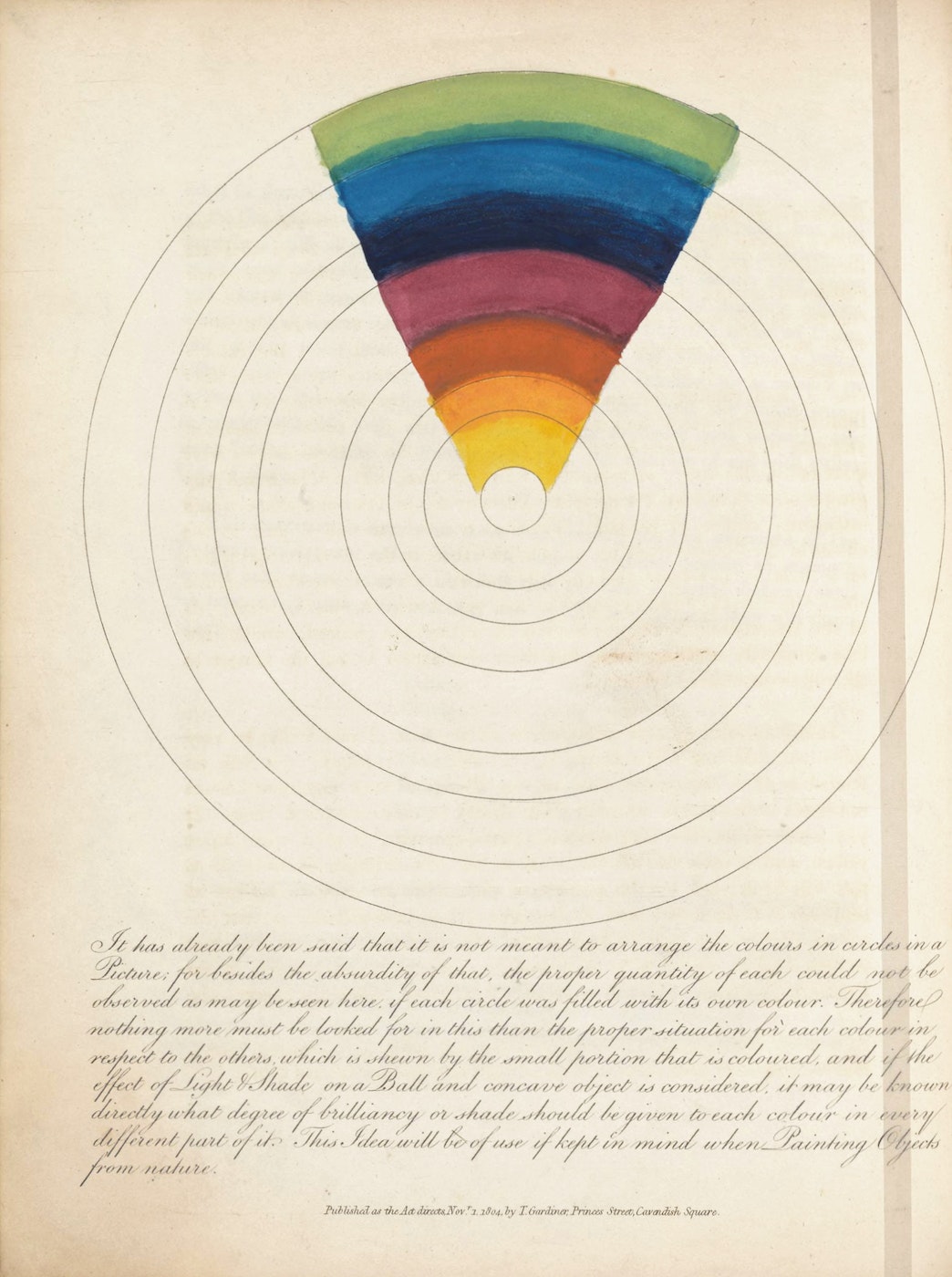

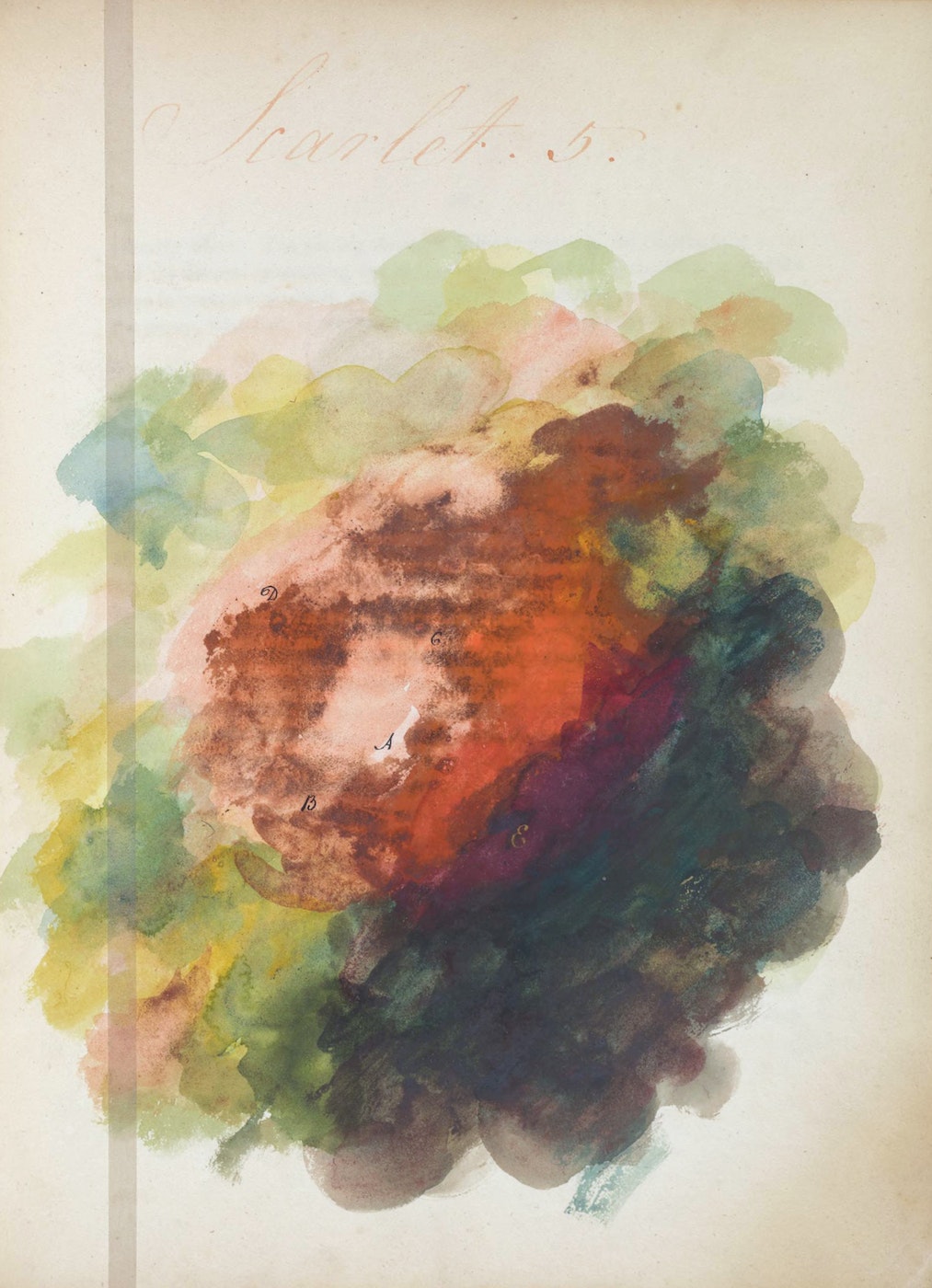

Gartside dressed her philosophy in what Ann Bermingham calls “the very modesty of the genre” of watercolor painting guides, the writing of which constituted a respectable outlet for women, where critical thought was not. The author gestures toward this state of affairs in her introduction, stating that she does not “offer my opinion unasked,” and noting emphatically she can only teach “to the best of my knowledge.” Her knowledge turns out to be considerable. Moreover, Public Domain Review writes, her “hand colored illustrations for the Essay, unique to each volume, have been deemed some of the earlier examples of abstraction in painting.”

Indeed, Gartside’s detailed instructions on the practical application of theory seem to presage the abstractions of Vasily Kandinsky, who brought his personal metaphysics to the formulae in the 1923 book Concerning the Spiritual in Art. Unlike the Romantics of her time — and like the Modernists of two hundred years later — Gartside de-emphasized individual genius while stressing the importance of theoretical understanding. Only through a knowledge of color theory and psychology, she writes boldly, could one achieve “command” of the art and make it their own, as she surely did in her illustrations. Joseph Litts points out in an essay for Material Matters:

Gartside used her medium of watercolor painting to engage with contemporary debates on color. Her understanding of color and color theory is the significant contribution of her book. She recasts both Isaac Newton’s theory of prismatic color and Sir William Herschel’s theory of radial color by creating a “color ball” that wraps the chromatic prism into a continual spectrum. Such a color ball anticipates Goethe’s attempts to put color into wheels, a shift from earlier grid representations.

Though Gartside would not claim the mantle of genius for herself or her readers (and she avoids fuzzy talk of inspiration, the muses, and so forth), we may place her confidently in the company of great color theorists and illustrators. And we might also see how her work shows an approach not taken, or not taken until a couple centuries later.

“There is no other example of a representation of colour systems,” Loske writes, “that is as inventive and radical as Gartside’s colour blots.” Learn more about Loske’s discovery of Gartside’s work in Kelly Grover’s BBC essay “The Women Who Redefined Colour.” See more of Gartside’s watercolors at the Public Domain Review.

Related Content:

The Vibrant Color Wheels Designed by Goethe, Newton & Other Theorists of Color (1665–1810)

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

Leave a Reply