The popularity of graphic novels (and more than a few extremely lucrative superhero movie franchises) have conferred respectability on comics.

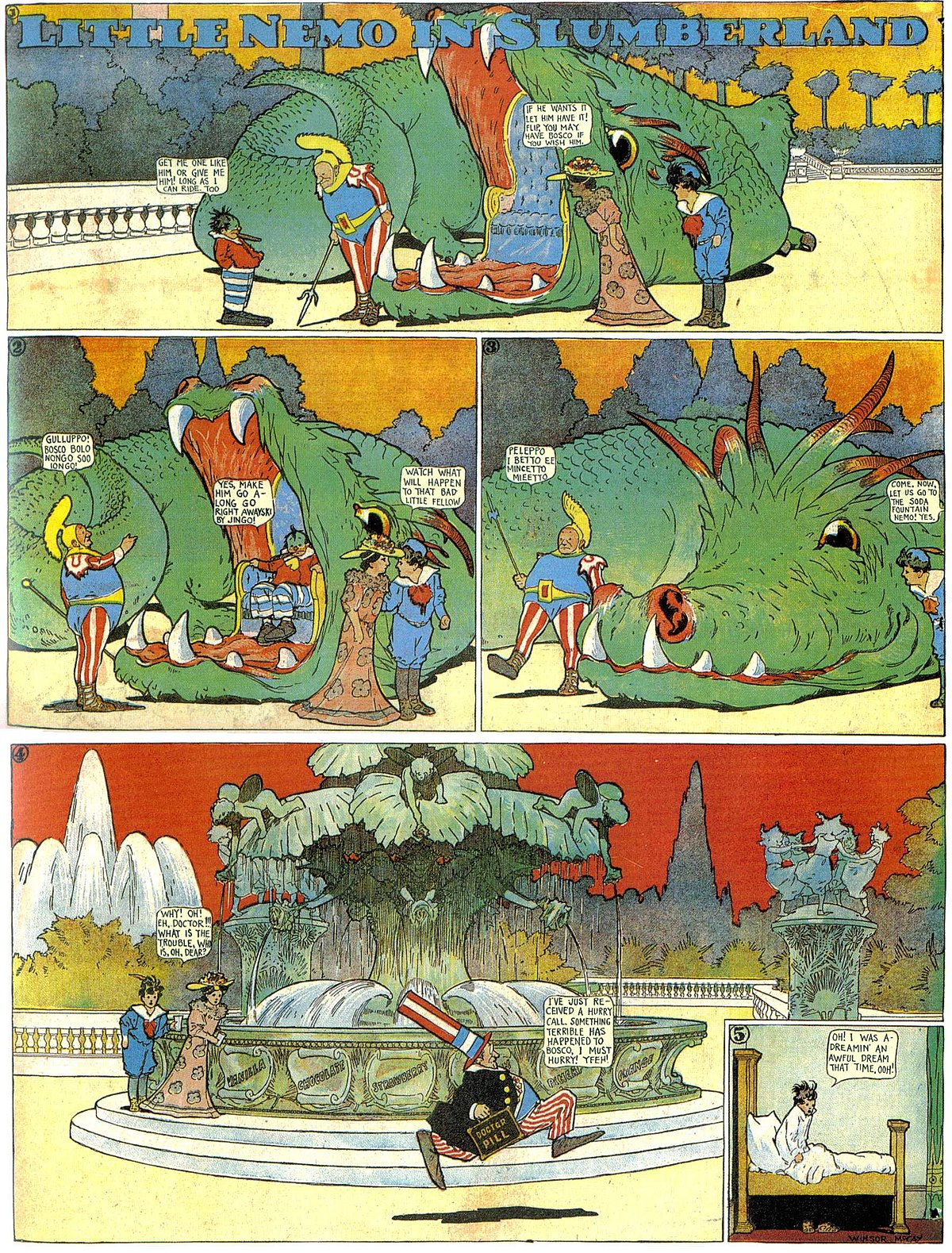

Handsome reissues of such stunning early works as Winsor McKay’s Little Nemo in Slumberland, George Herriman’s Krazy Kat, and Frank King’s Walt and Skeezix suggest that readers’ appetite for vintage comics extends deeper and further back than mere nostalgia for the Sunday funnies of their youth.

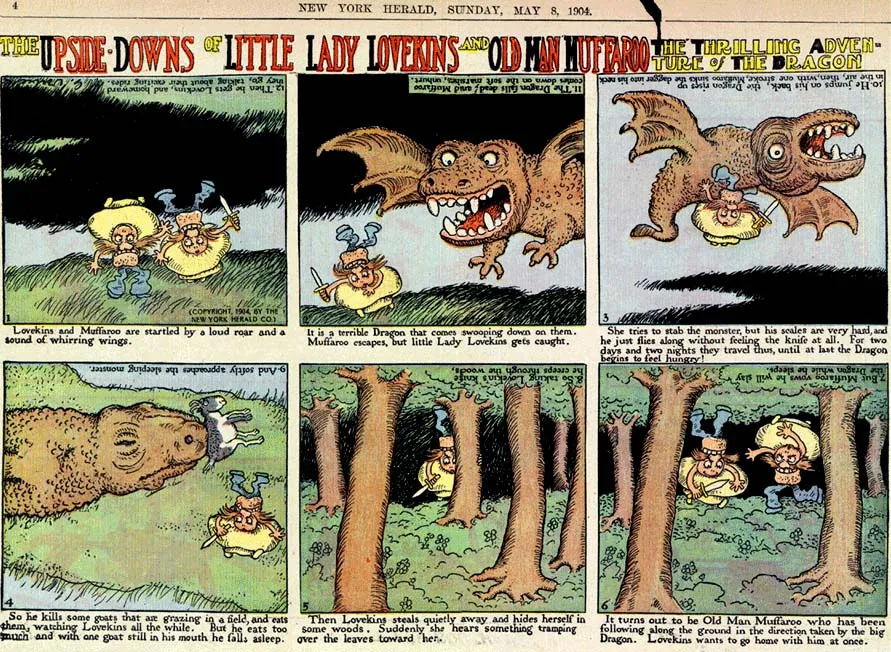

Artist Andy Bleck’s Andy’s Early Comics Archive is an excellent resource for those seeking to discover early examples of the form that have yet to be reissued in a collected edition. (Fair warning: reflecting the attitudes of the time, the collection does inevitably contains some racist imagery. Such imagery won’t be on display in this post.)

Bleck, the creator of Konky Kru, a beautifully simple, wordless series, as well as several self-published mini comics, takes a historian’s interest in his subject, beginning with the William Hogarth engravings A Harlot’s Progress from 1730:

The famous ‘progressions’ by Hogarth were not actually comics. The images don’t lead into and don’t interact with each other. Each shows a distinct, separate stage of a longer story. However, because of their great popularity, they established the very notion of telling entertaining stories with a series of pictures and so became a highly influential stepping stone for future developments.

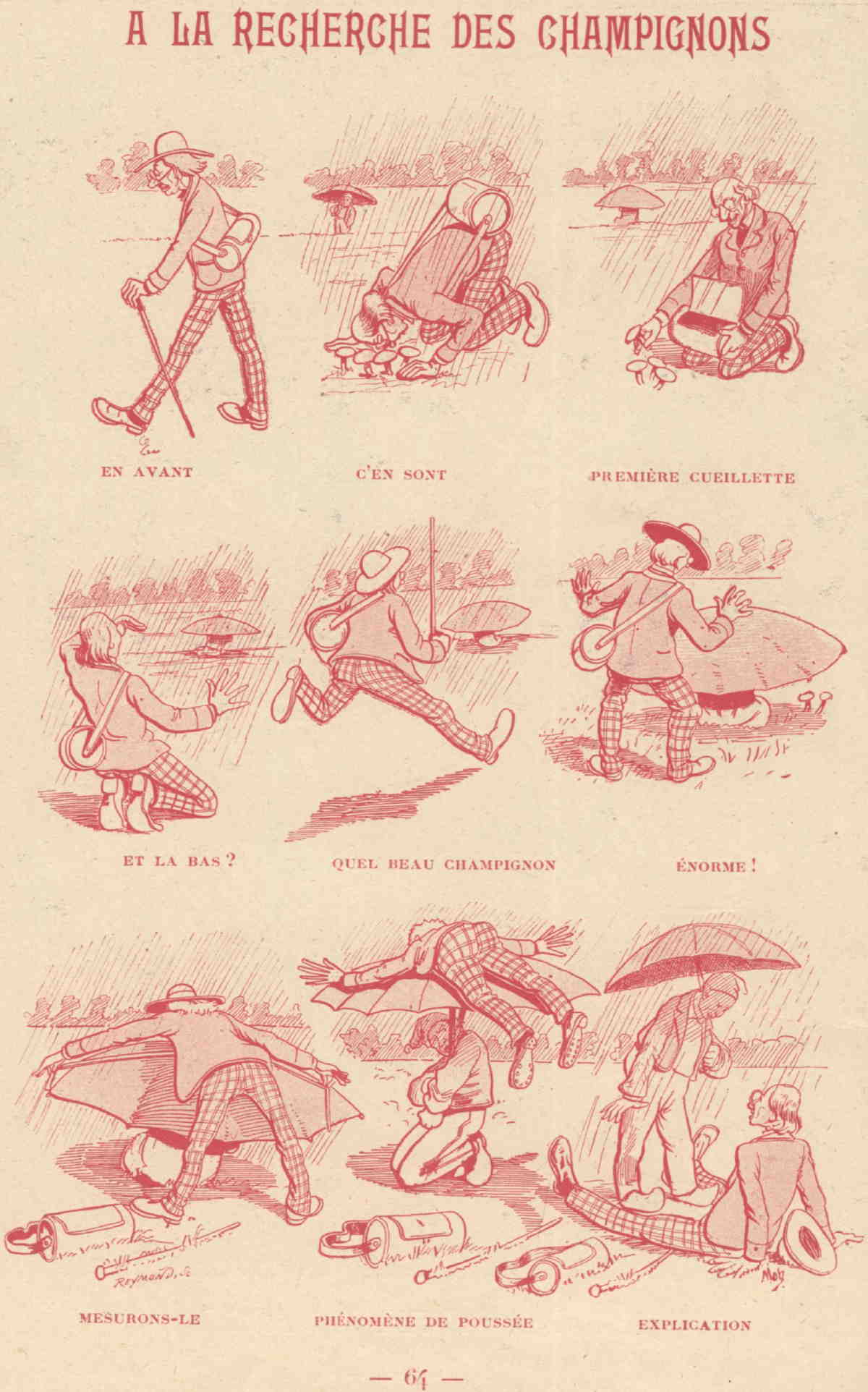

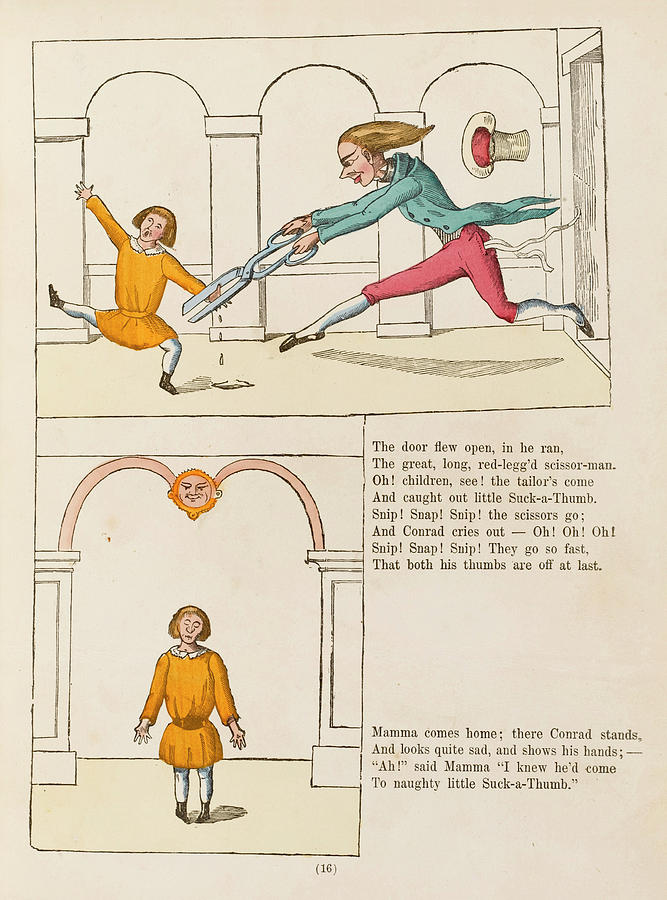

He also cites the influence of British political cartoons, Chinese woodcuts, illustrated fairy tales and nursery rhymes, and Heinrich Hoffmann’s Struwwelpeter, a book that terrified children into behaving by depicting the monstrous consequences befalling those who failed to do so.

Ironically, Franz Joseph Goez’s Lenardo und Blandine, an actual graphic novelette from 1783, “probably had little influence:”

It was too ahead of its time as far as the comic structure is concerned. In content, it was delightfully very much of its time, full of outrageous melodrama.

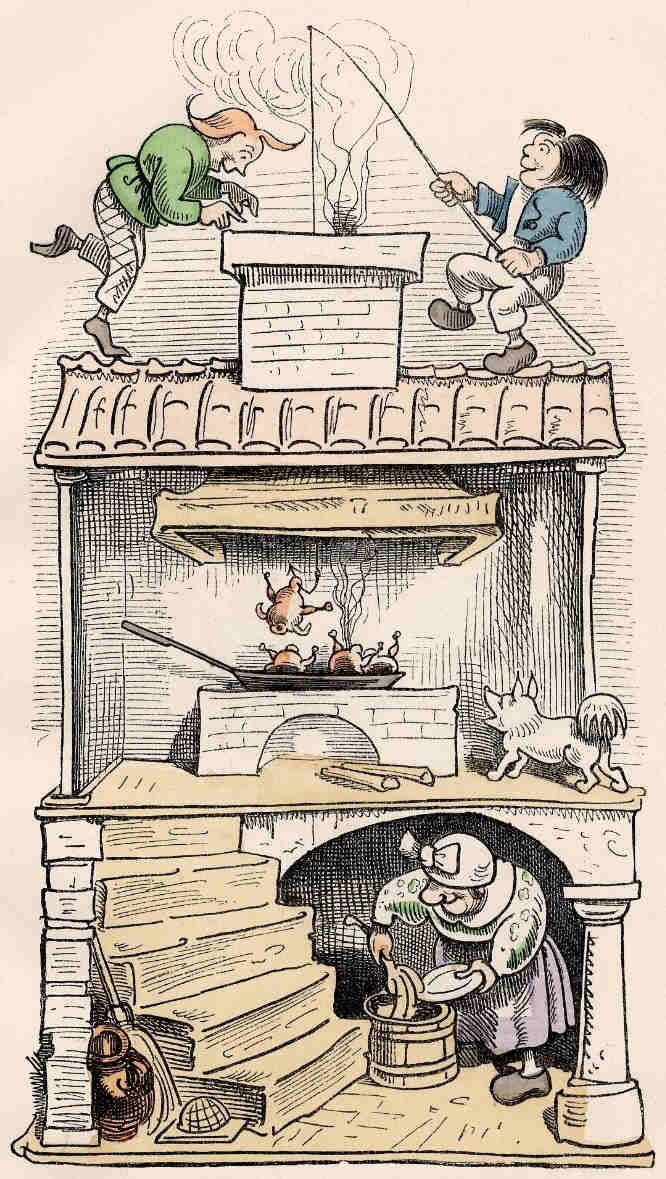

Things continued to evolve in the second half of the 19th-century, with picture broadsheets for children, such as the ones starring Wilhelm Busch’s wildly popular Max and Moritz. (See an English translation here.)

Bleck traces the birth of modern comics, whose storytelling vocabulary continues today, to the beginning of the 20th century, with American newspaper strips and particularly, the Sunday funnies:

The newspaper format was much larger and cheaper, providing a lot more empty space to fill. The audience was less sophisticated, but (possibly because of this) more open to a particular type of experimentation, despite the dumb and lowbrow humor… these American Sunday pages became the breeding ground for something new. Weirder, rougher, slapdashier. Also easier, for children, but not childish. More popular. More … somethingier.

Maybe it was that new type of human being, the urban immigrant, who was most prepared and eager to pay for all this new visual goings on.

Andy’s Early Comics Archive can be searched chronologically, or alphabetically by artist’s name. Enter here.

Related Content

Read The Very First Comic Book: The Adventures of Obadiah Oldbuck (1837)

Download Over 22,000 Golden & Silver Age Comic Books from the Comic Book Plus Archive

Download 15,000+ Free Golden Age Comics from the Digital Comic Museum

- Ayun Halliday is the Chief Primatologist of the East Village Inky zine and author, most recently, of Creative, Not Famous: The Small Potato Manifesto. Follow her @AyunHalliday.

Leave a Reply