Late in life, Kingsley Amis declared that he would henceforth read only novels opening with the sentence “A shot rang out.” On one level, this would have sounded bizarre coming from one of Britain’s most prominent men of letters. But on another it aligned with his long-demonstrated appreciation of genre fiction, including not just stories of crime but also of high technology and space exploration. His lifelong interest in the latter inspired the Christian Gauss Lectures he delivered at Princeton in 1958, published soon thereafter as New Maps of Hell: A Survey of Science Fiction, a book that sees him trace the history of the genre well back beyond his own boyhood — about eighteen centuries beyond it.

“Histories of science fiction, as opposed to ‘imaginative literature,’ usually begin, not with Plato or The Birds of Aristophanes or the Odyssey, but with a work of the late Greek prose romancer Lucian of Samosata,” Amis writes. He refers to what scholars now know as A True Story (Ἀληθῆ διηγήματα), a novella-length fiction of the second century that has everything from space travel to interplanetary war to technology so advanced — as no less a sci-fi luminary than Arthur C. Clarke would put it much later — as to be indistinguishable from magic. At its core a work of fantastical satire, A True Story “deliberately piles extravagance upon extravagance for comic effect” in a rather un-science-fiction-like manner.

“Leaving aside the question whether there was enough science around in the second century to make science fiction feasible,” Amis writes, “I will merely remark that the sprightliness and sophistication of the True History” — as he knew the work — “make it read like a joke at the expense of nearly all early-modern science fiction, that written between, say, 1910 and 1940,” which he himself would have grown up reading.

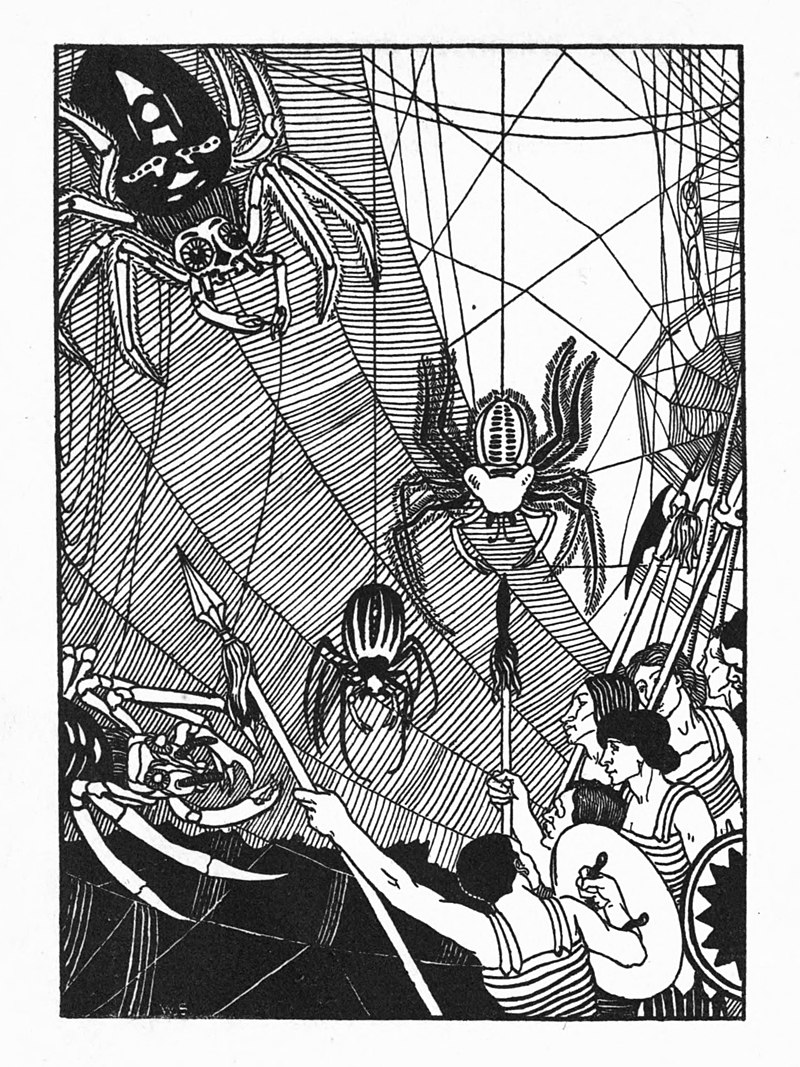

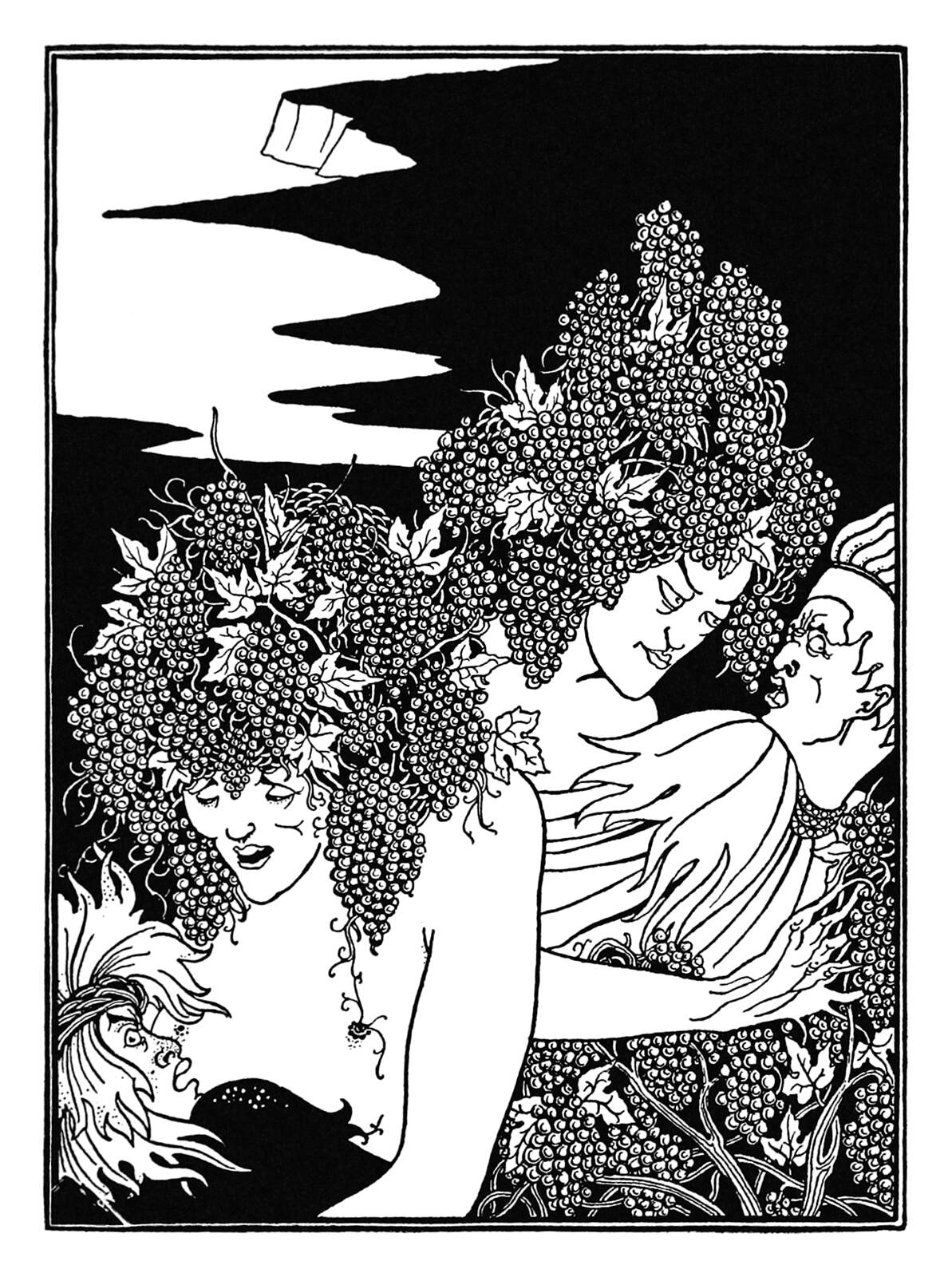

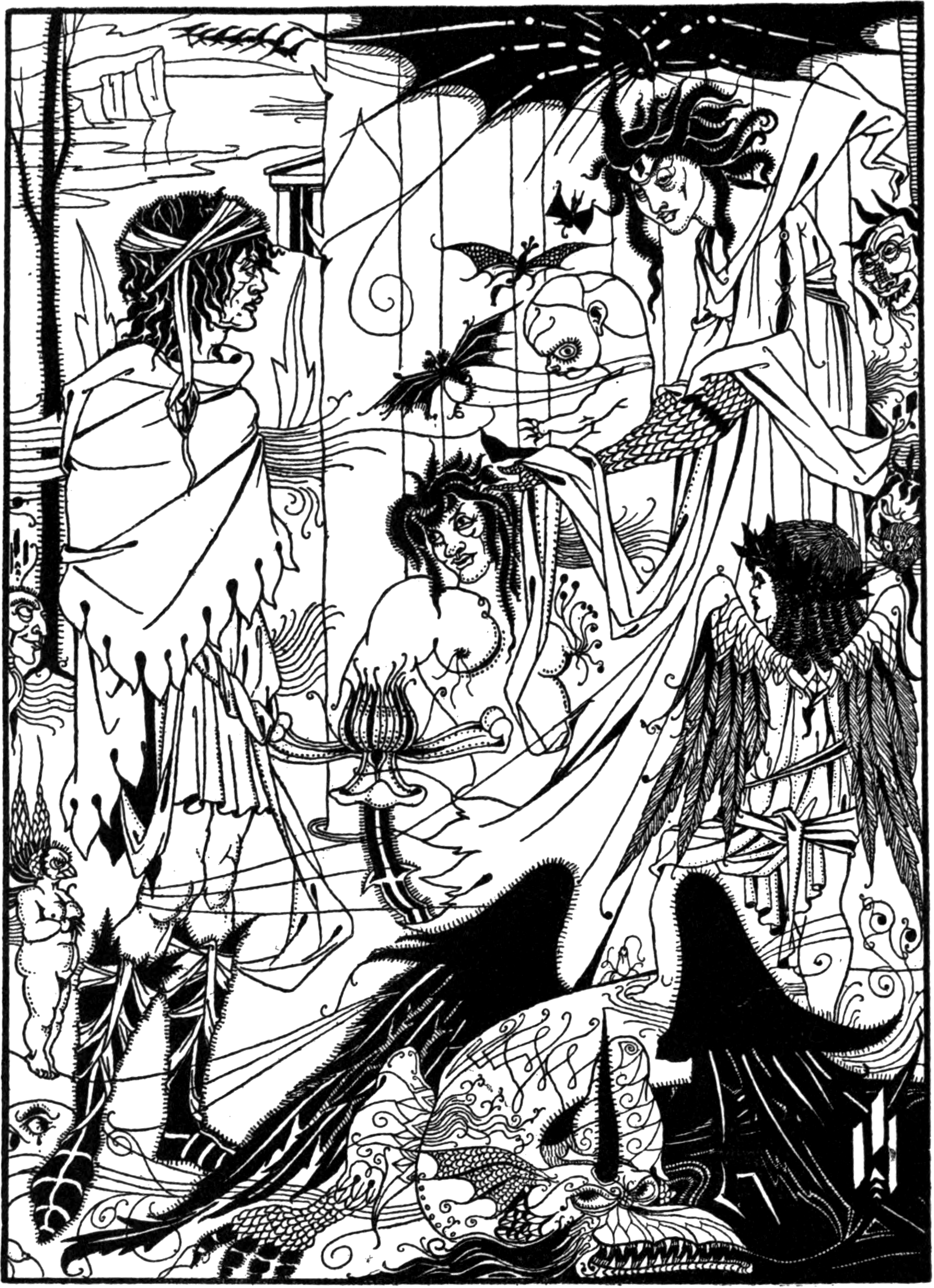

In the video by at the top of the post, filmmaker Gregory Austin McConnell summarizes Lucian’s entire travelogue, not neglecting to mention the river of wine, the tree-shaped women, the cities on the moon, the army of the sun, the battlefield-spinning space spiders, the dogs who ride on winged acorns, the floating sentient lamps, and the 187 and ½ mile-long whale.

This clearly isn’t what we’d now call “hard” science fiction. So how, exactly, to label it? Such arguments erupt over every major work of genre fiction, even from antiquity. A True Story contains elements of what would become comedy sci-fi, military sci-fi, and even the fantasy-and-sci-fi-hybridizing “space opera” most popularly exemplified by Star Wars and its many sequels. Categorization quibbles aside, what matters about any work in the broader tradition of “speculative fiction” is whether it fires up the reader’s imagination, and Lucian’s work has done it for not just ancients but moderns like the 19th-century artists William Strang and Aubrey Beardsley, whose illustrations from 1894 editions of A True Story appear above. Now that “science fiction rules the cinematic landscape,” as McConnell puts it, who will adapt it for us postmoderns?

Related content:

When Astronomer Johannes Kepler Wrote the First Work of Science Fiction, The Dream (1609)

Mythos: An Animation Retells Timeless Greek Myths with Abstract Modern Designs

The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction: 17,500 Entries on All Things Sci-Fi Are Now Free Online

Isaac Asimov Recalls the Golden Age of Science Fiction (1937–1950)

Free Science Fiction Classics Available on the Web

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities, the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.

Leave a Reply