Anita Berber, the taboo-busting, sexually omnivorous, fashion forward, frequently naked star of the Weimar Republic cabaret scene, tops our list of performers we really wish we’d been able to see live.

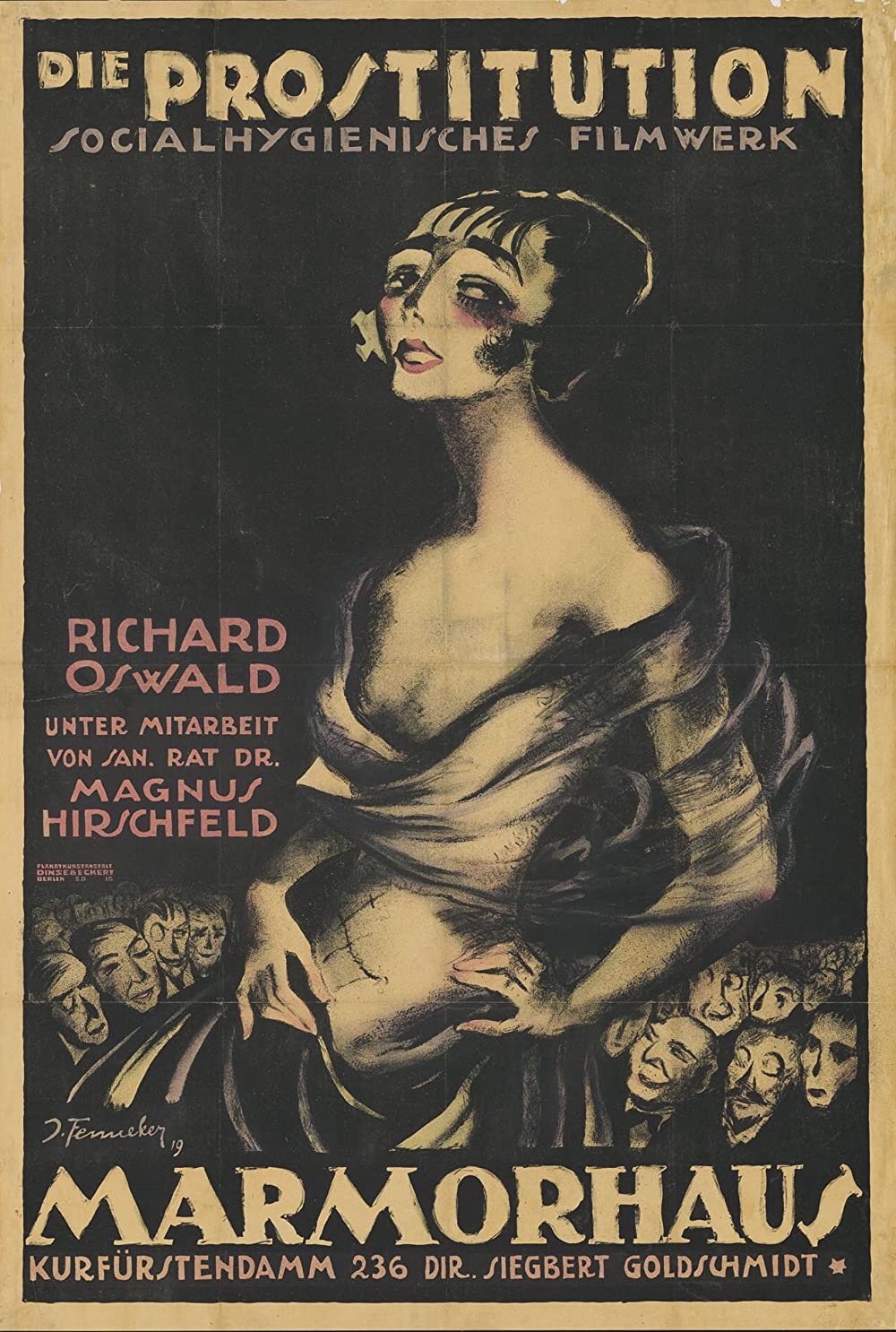

While Berber acted in 27 films, including Prostitution, director Fritz Lang’s Dr. Mabuse: The Gambler, and Different from the Others, which film critic Dennis Harvey describes as “the first movie to portray homosexual characters beyond the usual innuendo and ridicule,” we have a strong hunch that none of these appearances can compete with the sheer audacity of her stage work.

Audiences at Berlin’s White Mouse cabaret (some wearing black or white masks to conceal their identities) were titillated by her Expressionistic nude solo choreography, as well as the troupe of six teenaged dancers under her command.

As biographer Mel Gordon writes in The Seven Addictions and Five Professions of Anita Berber: Weimar Berlin’s Priestess of Depravity, Berber, often described as a “stripper”, displayed the passion of a serious artist, “respond(ing) to the audience’s heckling with show-stopping obscenities and indecent provocations:”

Berber had been known to spit brandy on them or stand naked on their tables, dousing herself in wine whilst simultaneously urinating… It was not long before the entire cabaret one night sank into a groundswell of shouting, screams and laughter. Anita jumped off the stage in fuming rage, grabbed the nearest champagne bottle and smashed it over a businessman’s head.

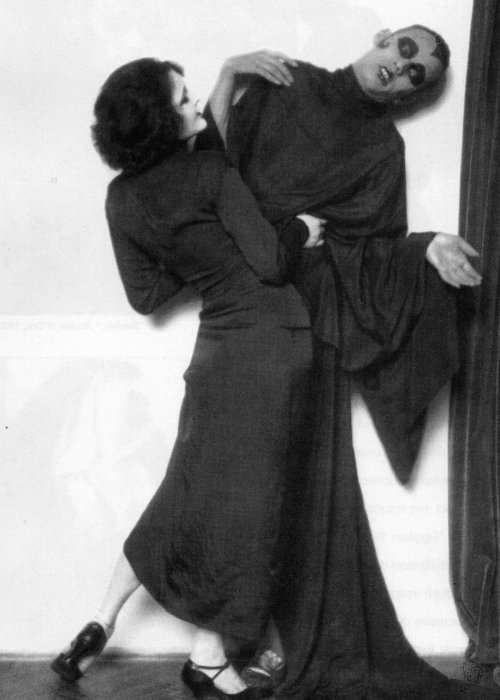

Her collaborations with her second husband, dancer Sebastian Droste, carried Berber into increasingly transgressive territory, both onstage and off.

According to translator Merrill Cole, in the introduction to the 2012 reissue of Dances of Vice, Horror and Ecstasy, a book of Expressionist poems, essays, photographs, and stage designs which Droste and Berber co-authored, “even the biographical details seduce:”

…a bisexual sometimes-prostitute and a shady figure from the male homosexual underworld, united in addiction to cocaine and disdain for bourgeois respectability, both highly talented, Expressionist-trained dancers, both beautiful exhibitionists, set out to provide the Babylon on the Spree with the ultimate experience of depravity, using an art form they had helped to invent for this purpose. Their brief marriage and artistic interaction ended when Droste became desperate for drugs and absconded with Berber’s jewel collection.

This, and the description of Berber’s penchant for “haunt(ing) Weimar Berlin’s hotel lobbies, nightclubs and casinos, radiantly naked except for an elegant sable wrap, a pet monkey hanging from her neck, and a silver brooch packed with cocaine,” do a far more evocative job of resurrecting Berber, the Weimar sensation, than any wordy, blow-by-blow attempt to recreate her shocking performances, though we can’t fault author Karl Toepfer, Professor Emeritus of Theater Arts at San Jose State University, for trying.

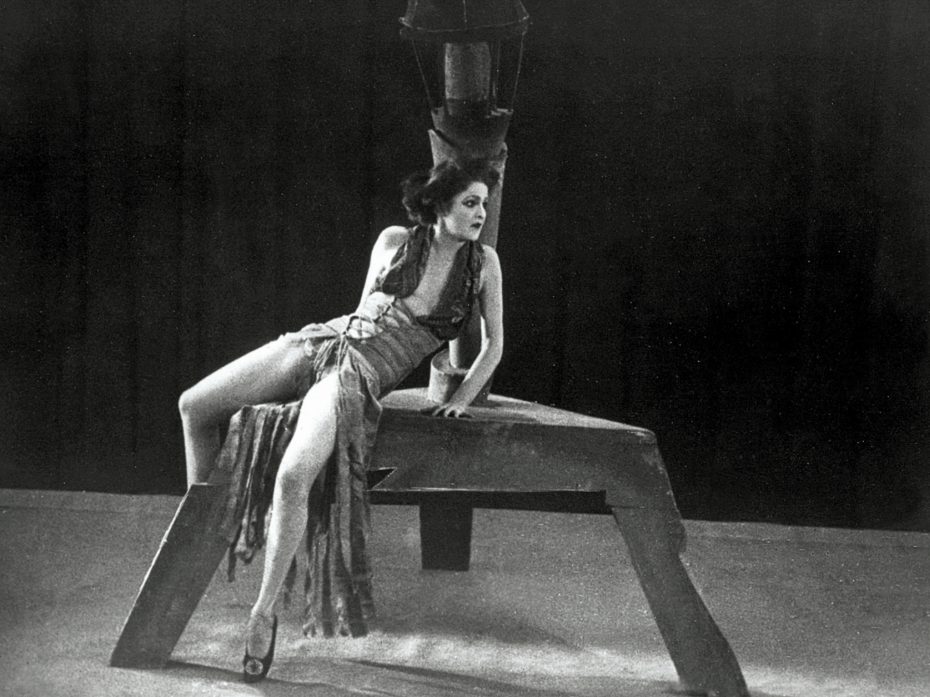

In Empire of Ecstasy: Nudity and Movement in German Body Culture, 1910–1935, Toepfer draws heavily on Czech choreographer Joe Jenčík’s eyewitness observations, to reconstruct Berber’s most notorious dance, Cocaine, beginning with the “ominous scenery by Harry Täuber featuring a tall lamp on a low, cloth-covered table:”

This lamp was an expressionist sculpture with an ambiguous form that one could read as a sign of the phallus, an abstraction of the female dancer’s body, or a monumental image of a syringe, for a long, shiny needle protruded from the top of it…It is not clear how nude Berber was when she performed the dance. Jenčík, writing in 1929, flatly stated that she was nude, but the famous Viennese photographer Madame D’Ora (Dora Kalmus) took a picture entitled “Kokain” in which Berber appears in a long black dress that exposes her breasts and whose lacing, up the front, reveals her flesh to below her navel.

In any case, according to Jenčík, she displayed “a simple technique of natural steps and unforced poses.” But though the technique was simple, the dance itself, one of Berber’s most successful creations, was apparently quite complex. Rising from an initial condition of paralysis on the floor (or possibly from the table, as indicated by Täuber’s scenographic notes), she adopted a primal movement involving a slow, sculptured turning of her body, a kind of slow-motion effect. The turning represented the unraveling of a “knot of flesh.” But as the body uncoiled, it convulsed into “separate parts,” producing a variety of rhythms within itself. Berber used all parts of her body to construct a “tragic” conflict between the healthy body and the poisoned body: she made distinct rhythms out of the movement of her muscles; she used “unexpected counter-movements” of her head to create an anguished sense of balance; her “porcelain-colored arms” made hypnotic, pendulumlike movements, like a marionette’s; within the primal turning of her body, there appeared contradictory turns of her wrists, torso, ankles; the rhythm of her breathing fluctuated with dramatic effect; her intense dark eyes followed yet another, slower rhythm; and she introduced the “most refined nuances of agility” in making spasms of sensation ripple through her fingers, nostrils, and lips. Yet, despite all this complexity, she was not afraid of seeming “ridiculous” or “painfully swollen.” The dance concluded when the convulsed dancer attempted to cry out (with the “blood-red opening of the mouth”) and could not. The dancer then hurled herself to the floor and assumed a pose of motionless, drugged sleep. Berber’s dance dramatized the intense ambiguity involved in linking the ecstatic liberation of the body to nudity and rhythmic consciousness. The dance tied ecstatic experience to an encounter with vice (addiction) and horror (acute awareness of death).

A noble attempt, but forgive us if we can’t quite picture it…

And what little evidence has been preserved of her screen appearances exists at a similar remove from the dark subject matter she explicitly referenced in her choreographed work — Morphine, Suicide, The Corpse on the Dissecting Table…

Cole opines:

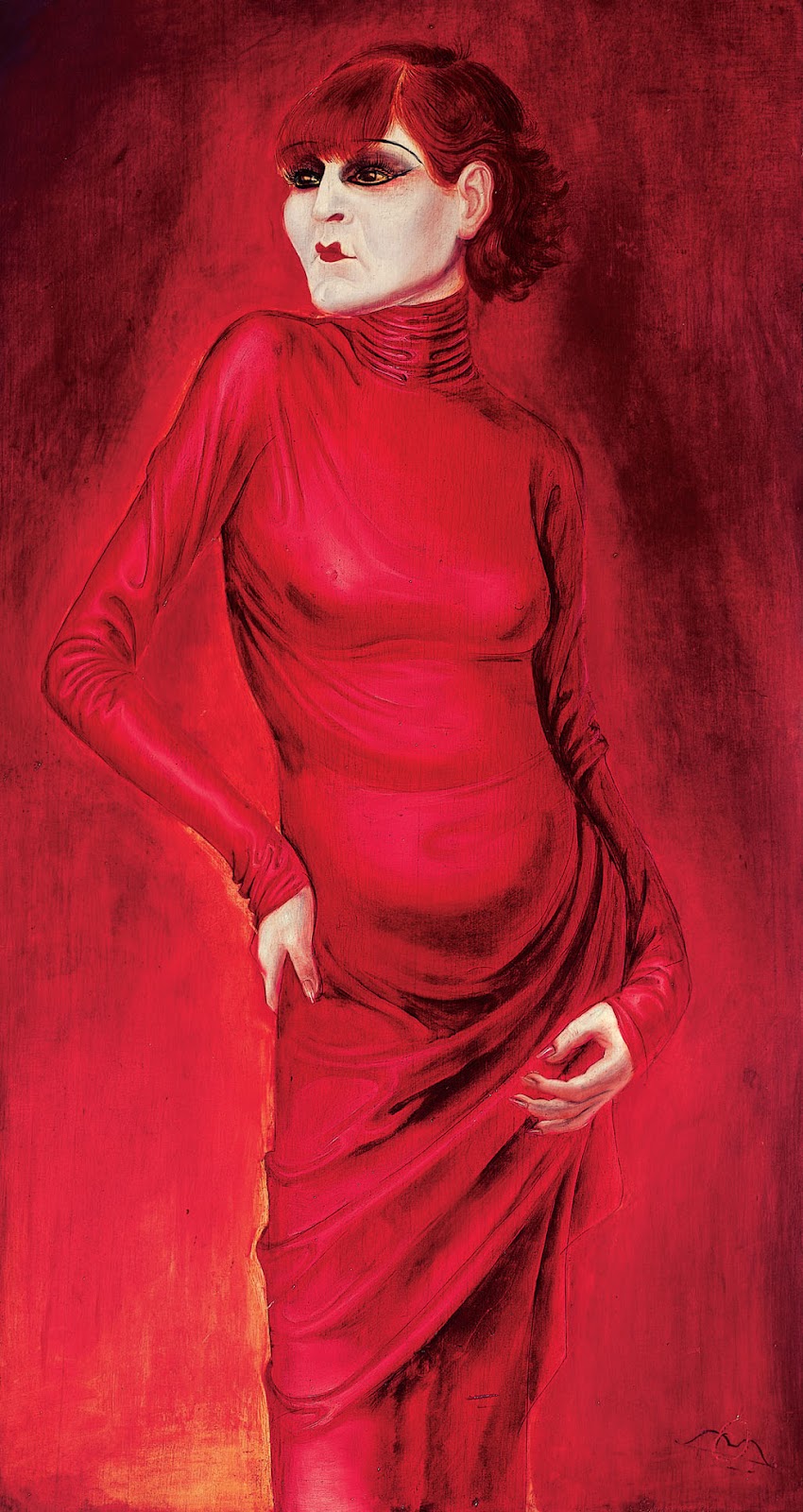

There are a number of narrative accounts of her dances, some pinned by professional critics, and almost all commending her talent, finesse, and mesmerizing stage presence. We also have film images from the various silent films in which she played bit parts. There exist, too, many still photographs of Berber and Droste, as well as renditions of Berber by other artists, most prominently the Dadaist Otto Dix’s famous scarlet-saturated portrait. In regard to the naked dances, unfortunately, we have no moving images, no way to watch directly how they were performed.

For a dishy overview of Anita Berber’s personal life, including her alleged dalliances with actress Marlene Dietrich, author Lawrence Durrell, and the King of Yugoslavia, her influential effect on director Leni Riefenstahl, and her sad demise at the age of 29, a “carrion soul that even the hyenas ignored,” take a peek at Victoria Linchong’s biographical essay for Messy Nessy Chic, or better yet, Iron Spike’s Twitter thread.

Berber was addicted to alcohol, cocaine, opium, and morphine. But one of her favorite drugs was chloroform and ether, mixed in a bowl. She would stir the bowl with the bloom of a white rose, and then eat the petals.

Have you ever heard anything so extra in your ENTIRE LIFE. pic.twitter.com/sh9xL3it0E

— Iron Spike (@Iron_Spike) January 11, 2020

- Ayun Halliday is the Chief Primatologist of the East Village Inky zine and author, most recently, of Creative, Not Famous: The Small Potato Manifesto. Follow her @AyunHalliday.

Related Content

The Nazis’ 10 Control-Freak Rules for Jazz Performers: A Strange List from World War II

Download Hundreds of Issues of Jugend, Germany’s Pioneering Art Nouveau Magazine (1896–1940)

Scenes of Berber performing are very rare. Some of the most interesting extended footage I’ve seen is from the original horror anthology film “Eerie Tales” (or “Uncanny Tales) from 1919. It’s out there online for those interested.