What should you do if you come across a manticore? Would you even know how to identify it? An unlikely occurrence, you say? Perhaps. But if you lived in Europe in the Middle Ages – and you were the type to believe such tales – you might expect to see one someday. Wouldn’t it be useful to have a field guide? You’d want it on paper (or parchment): no one’s carrying smartphones in misty 13th century York or over the rocky highlands of 15th century Lombardy. You could consult a reigning expert of the time, such as Sir John Mandeville, who either saw such things as blemmyae (headless humans with faces in their chests) near Ethiopia, or made them up. But this didn’t matter much. Truth and fiction didn’t have such rigid boundaries. Yet books were rare, and anyway, few people could read. If only there were YouTube.…

“Medieval zoology is bizarre,” says the narrator of the video above — a brief “Field Guide to Bizarre Medieval Monsters” — “because half the creatures don’t even exist, and those that do look very, very strange.” Your average medieval European couldn’t visit zoos full of exotic animals (rare exceptions like the Tower of London Menagerie notwithstanding), nor could they travel the world and see what creatures thrived in other climes.

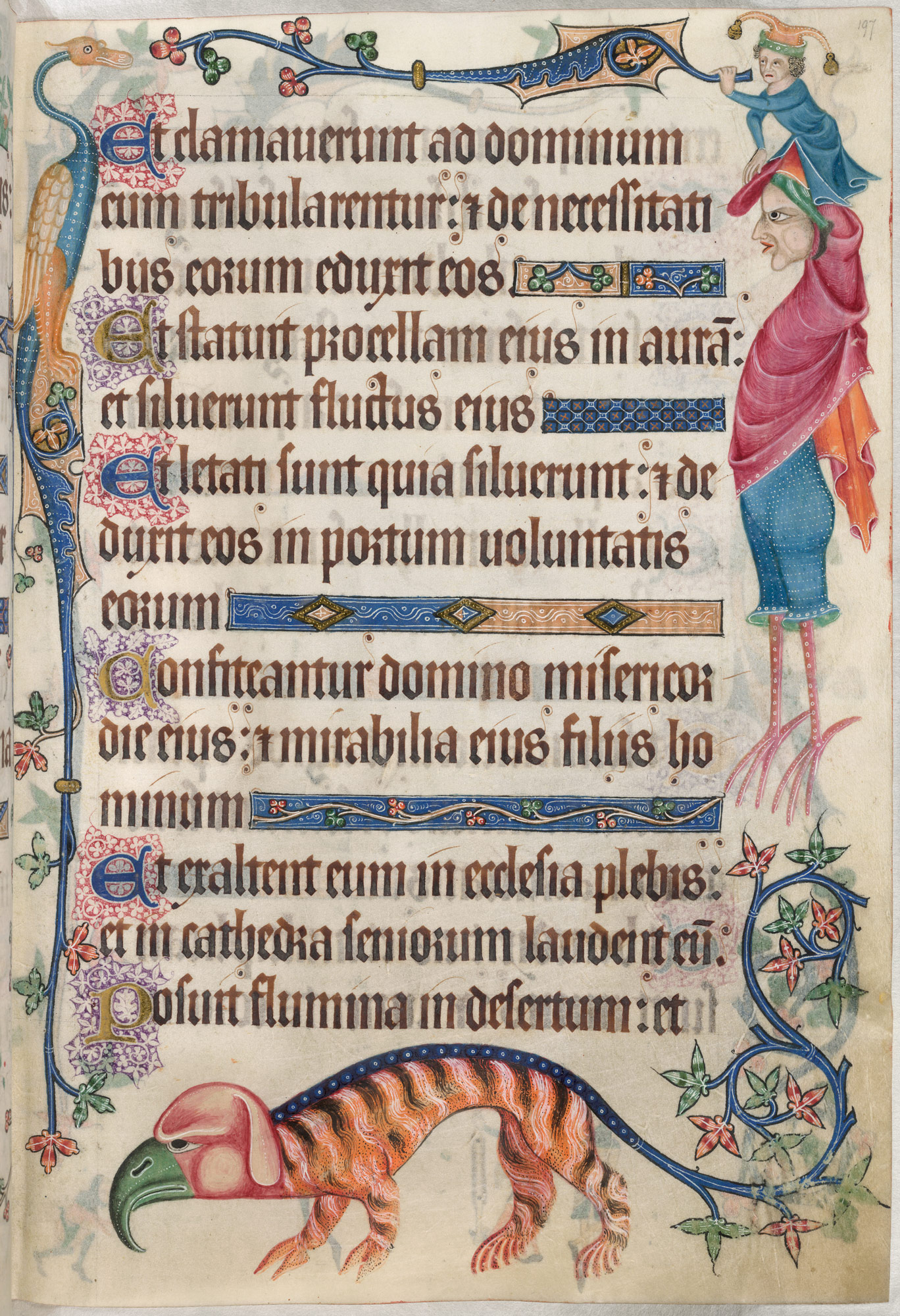

They were forced to rely on the garbled accounts, or outright lies, of sailors, merchants, and other travelers, and the odd illustrations found in illuminated manuscripts. These blended travelogue, native folk elements, the weird imaginings of alchemy and demonology, and the myths and legends of medieval romance to create “a world where mythology and biology blend together.”

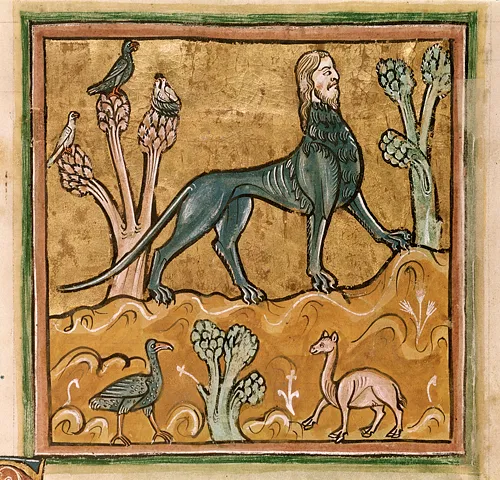

Dragons, unicorns, dog-headed saints.… You’ll find these and many more in the video field guide at the top and others online from the Cleveland Museum of Art and Medievalists.net, which describes our friend the manticore as a creature “having the head of a man, the body of a lion, and the tail of a scorpion.”

Many ancient and medieval monsters were hybrids of different animals, such as the Tarasque, which our field guide narrator explains lies “somewhere between a dragon and a tortoise.”

To find out its origins, you’ll have to keep watching. To read the original sources of this bizarre medieval zoology, see the British Library’s Medieval Monster’s collection, which includes aviaries, bestiaries, miscellanies, books of hours, and psalters, like the big page above from the Luttrell Psalter, a striking example of monstrous illustration. While we may never expect to see any of these creatures in the flesh, we can see more of them on the page (or screen) than anyone who lived in medieval Europe.

Related Content:

1,000-Year-Old Illustrated Guide to the Medicinal Use of Plants Now Digitized & Put Online

Wonderfully Weird & Ingenious Medieval Books

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

Leave a Reply