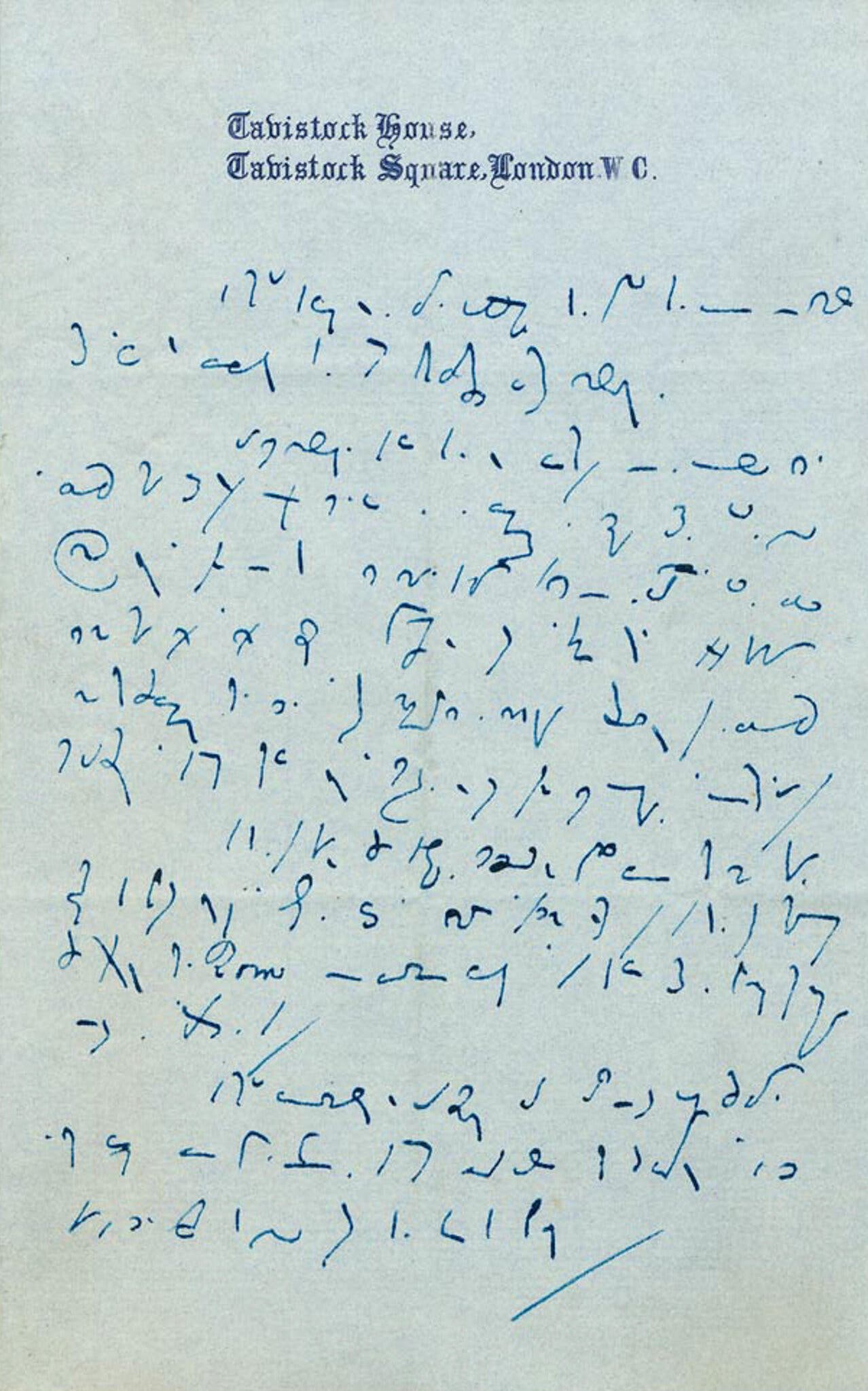

We can describe the writing of Charles Dickens in many ways, but never as impenetrable. The most popular novelist of his day, he wrote for the broadest possible audience, serializing his stories in newspapers before putting them between covers. This hardly prevented him from demonstrating a mastery of the English language whose mark remains detectable in our own rhetoric and literary prose more than 150 years after his death. But Dickens wrote both publicly and privately, and in the case of the latter he could write quite privately indeed: in documents for his own eyes only, he made use of a shorthand that he called it “the devil’s handwriting,” and which has long been devilishly impenetrable to scholars.

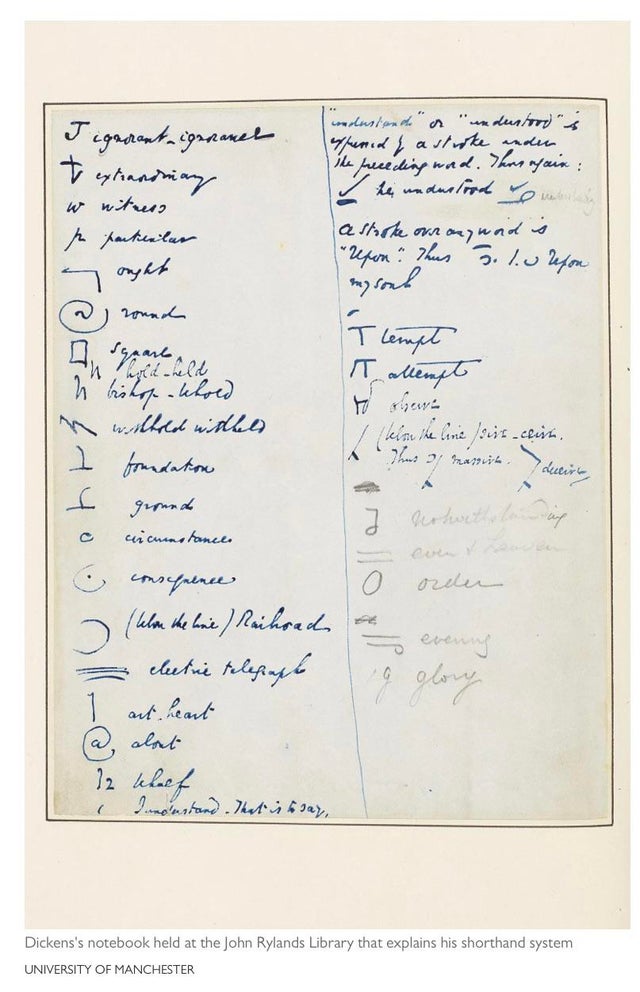

Dickens “learned a difficult shorthand system called Brachygraphy and wrote about the experience in his semi-autobiographical novel, David Copperfield, calling it a ‘savage stenographic mystery,’ ” says The Dickens Code, a web site dedicated to solving that mystery.

A former court reporter, “Dickens used shorthand throughout his life but while he was using the system, he was also changing it. So the hooks, lines, circles and squiggles on the page are very hard to decipher.” The Dickens Code project thus offered up t0 anyone who could transcribe his shorthand a sum of 300 British pounds — which might not sound like much, but imagine how grand a sum it would have been in Dickens’ day.

Besides, the internet’s cryptography enthusiasts hardly require much of an incentive to get to work on such a long-uncracked code as this. “The winner of the competition, Shane Baggs, a computer technical support specialist from San Jose, Calif., had never read a Dickens novel before,” writes the New York Times’ Jenny Gross. “Mr. Baggs, who spent about six months working on the text, mostly after work, said that he first heard about the competition through a group on Reddit dedicated to cracking codes and finding hidden messages.”

The document being decoded is a copy of a letter from 1859, the year Dickens was serializing A Tale of Two Cities. Writing to Times of London editor John Thaddeus Delane, “Dickens says that a clerk at the newspaper was wrong to reject an advertisement he wanted in the paper, promoting a new literary publication, and asks again for it to run,” report Gross. This seemingly trivial incident inspires the kind of “strong, direct language in the 19th century that showed the writer was angry.” Though 70 percent of this decorously bad-tempered letter has now been deciphered, The Dickens Code still has work to do and continues to enlist help from volunteers to do it, albeit without the prize money that is now presumably in Baggs’ possession. Let’s hope he uses it on the handsomest possible set of Dickens’ collected works.

Related content:

An Animated Introduction to Charles Dickens’ Life & Literary Works

Alice in Wonderland, Hamlet, and A Christmas Carol Written in Shorthand (Circa 1919)

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities, the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.

300 British pounds for coming up with the answer key😐

“53ND NUD3S” was really not that hard a code to crack, it turns out.

TLDR?

Helping

300 pounds 160 years ago is about 6600£ today

I like dickens in me

how much for solving the runic stone alphabet? 19 century plus old?!

how much for solving the runic stone alphabet? 19 century plus old?!BO******@*OL.COM

yet can we find a backer or publisher or agent? 26 plus said no! and they saw proof in 50 pgs! plus solutions! idiots all through the establishment!!