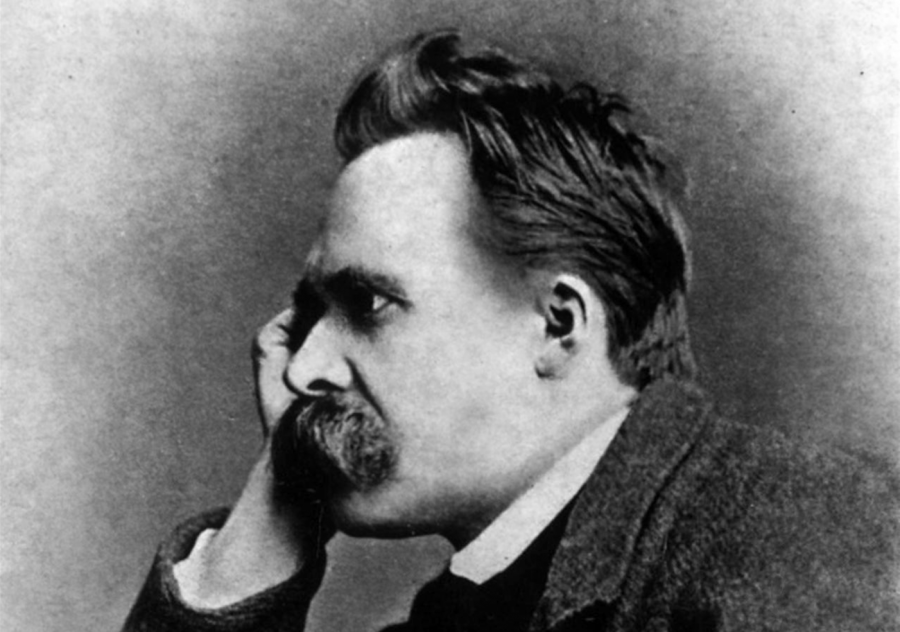

The life of Russian-born poet, novelist, critic, and first female psychologist Lou Andreas-Salomé has provided fodder for both salacious speculation and intellectual drama in film and on the page for the amount of romantic attention she attracted from European intellectuals like philosopher Paul Rée, poet Ranier Maria Rilke, and Friedrich Nietzsche. Emotionally intense Nietzsche became infatuated with Salomé, proposed marriage, and, when she declined, broke off their relationship in abrupt Nietzschean fashion.

For her part, Salomé so valued these friendships she made a proposal of her own: that she, Nietzsche and Rée, writes D.A. Barry at 3:AM Magazine, “live together in a celibate household where they might discuss philosophy, literature and art.” The idea scandalized Nietzsche’s sister and his social circle and may have contributed to the “passionate criticism” Salomé’s 1894 biographical study, Friedrich Nietzsche: The Man and His Works, received. The “much maligned” work deserves a reappraisal, Barry argues, as “a psychological portrait.”

In Nietzsche, Salomé wrote, we see “sorrowful ailing and triumphal recovery, incandescent intoxication and cool consciousness. One senses here the close entwining of mutual contradictions; one senses the overflowing and voluntary plunge of over-stimulated and tensed energies into chaos, darkness and terror, and then an ascending urge toward the light and most tender moments.” We might see this passage as charged by the remembrance of a friend, with whom she once “climbed Monte Sacro,” she claimed, in 1882, “where he told her of the concept of the Eternal Recurrence ‘in a quiet voice with all the signs of deepest horror.’”

We should also, perhaps primarily, see Salomé’s impressions as an effect of Nietzsche’s turbulent prose, reaching its apotheosis in his experimentally philosophical novel, Thus Spake Zarathustra. As a theorist of the embodiment of ideas, of their inextricable relation to the physical and the social, Nietzsche had some very specific ideas about literary style, which he communicated to Salomé in an 1882 note titled “Toward the Teaching of Style.” Well before writers began issuing “similar sets of commandments,” writes Maria Popova at Brain Pickings, Nietzsche “set down ten stylistic rules of writing,” which you can find, in their original list form, below.

1. Of prime necessity is life: a style should live.

2. Style should be suited to the specific person with whom you wish to communicate. (The law of mutual relation.)

3. First, one must determine precisely “what-and-what do I wish to say and present,” before you may write. Writing must be mimicry.

4. Since the writer lacks many of the speaker’s means, he must in general have for his model a very expressive kind of presentation of necessity, the written copy will appear much paler.

5. The richness of life reveals itself through a richness of gestures. One must learn to feel everything — the length and retarding of sentences, interpunctuations, the choice of words, the pausing, the sequence of arguments — like gestures.

6. Be careful with periods! Only those people who also have long duration of breath while speaking are entitled to periods. With most people, the period is a matter of affectation.

7. Style ought to prove that one believes in an idea; not only that one thinks it but also feels it.

8. The more abstract a truth which one wishes to teach, the more one must first entice the senses.

9. Strategy on the part of the good writer of prose consists of choosing his means for stepping close to poetry but never stepping into it.

10. It is not good manners or clever to deprive one’s reader of the most obvious objections. It is very good manners and very clever to leave it to one’s reader alone to pronounce the ultimate quintessence of our wisdom.

As with all such prescriptions, we are free to take or leave these rules as we see fit. But we should not ignore them. While Nietzsche’s perspectivism has been (mis)interpreted as wanton subjectivity, his veneration for antiquity places a high value on formal constraints. His prose, we might say, resides in that tension between Dionysian abandon and Apollonian cool, and his rules address what liberal arts professors once called the Trivium: grammar, rhetoric, and logic: the three supports of moving, expressive, persuasive writing.

Salomé was so impressed with these aphoristic rules that she included them in her biography, remarking, “to examine Nietzsche’s style for causes and conditions means far more than examining the mere form in which his ideas are expressed; rather, it means that we can listen to his inner soundings.” Isn’t this what great writing should feel like?

Salomé wrote in her study that “Nietzsche not only mastered language but also transcended its inadequacies.” (As Nietzsche himself commented in 1886, notes Hugo Drochon, he needed to invent “a language of my very own.”) Nietzsche’s bold-yet-disciplined writing found a complement in Salomé’s boldly keen analysis. From her we can also perhaps glean another principle: “No matter how calumnious the public attacks on her,” writes Barry, “particularly from [his sister] Elisabeth Förster-Nietzsche during the Nazi period in Germany, Salomé did not respond to them.”

Note: An earlier version of this post appeared on our site in December 2016.

If you would like to sign up for Open Culture’s free email newsletter, please find it here. It’s a great way to see our new posts, all bundled in one email, each day.

If you would like to support the mission of Open Culture, consider making a donation to our site. It’s hard to rely 100% on ads, and your contributions will help us continue providing the best free cultural and educational materials to learners everywhere. You can contribute through PayPal, Patreon, and Venmo (@openculture). Thanks!

Related Content:

The Daily Habits of Highly Productive Philosophers: Nietzsche, Marx & Immanuel Kant

Walter Kaufmann’s Classic Lectures on Nietzsche, Kierkegaard and Sartre (1960)

Writing Tips by Henry Miller, Elmore Leonard, Margaret Atwood, Neil Gaiman & George Orwell

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

Excellent piece. I am going to see if I find that book ” The Man and His Works”. Please put me on your mailing list at cd*******@*ol.com…

Thank you

Chad

Please place me on your list.

Send regular feedback