Even with 21st-century teaching aids, the written Japanese language isn’t the sort of thing one picks up in a few weeks’ study. A few hundred years ago it would’ve been much more difficult still, especially for those engaged in learning the sūtras or scriptures of Buddhism. “The stakes of correct recitation were high in the pre- and early modern era,” writes The Public Domain Review’s Hunter Dukes, “with strict rules for pronunciation existing since the 1100s, and sūtra recitation (dokyō) becoming an art form in the following century.” Imported from India and rewritten in classical Chinese with few clues as to how its words should actually be spoken, the Buddhist canon of east Asia set a mighty challenge even before the perfectly literate.

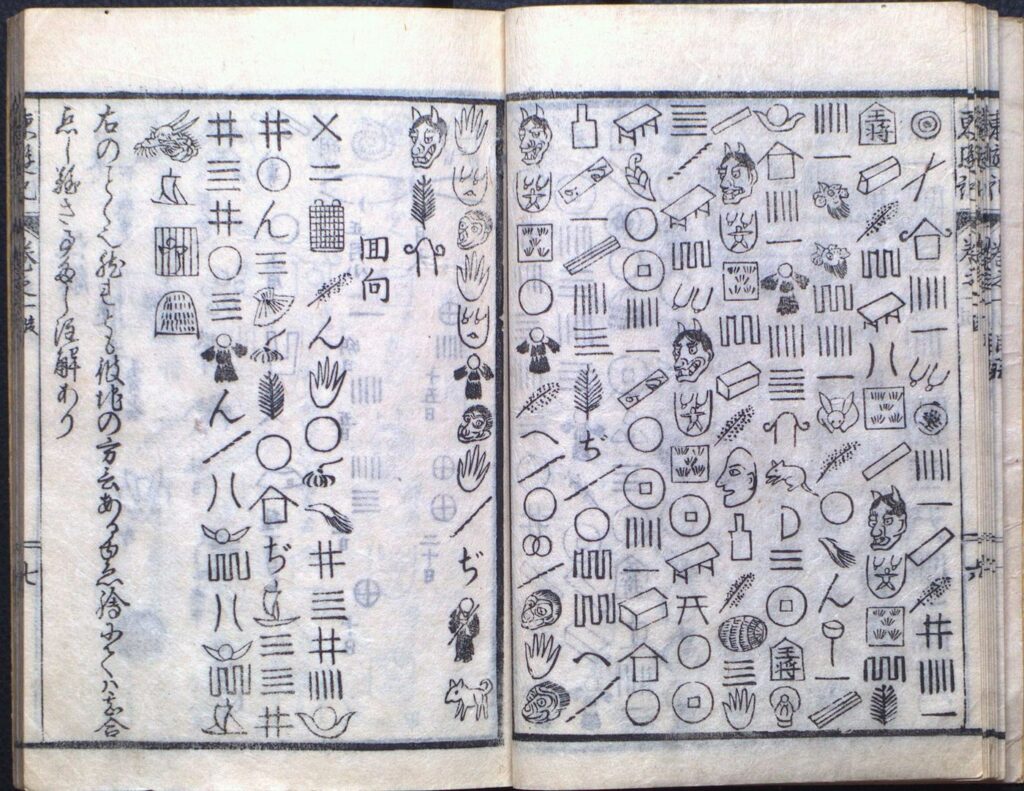

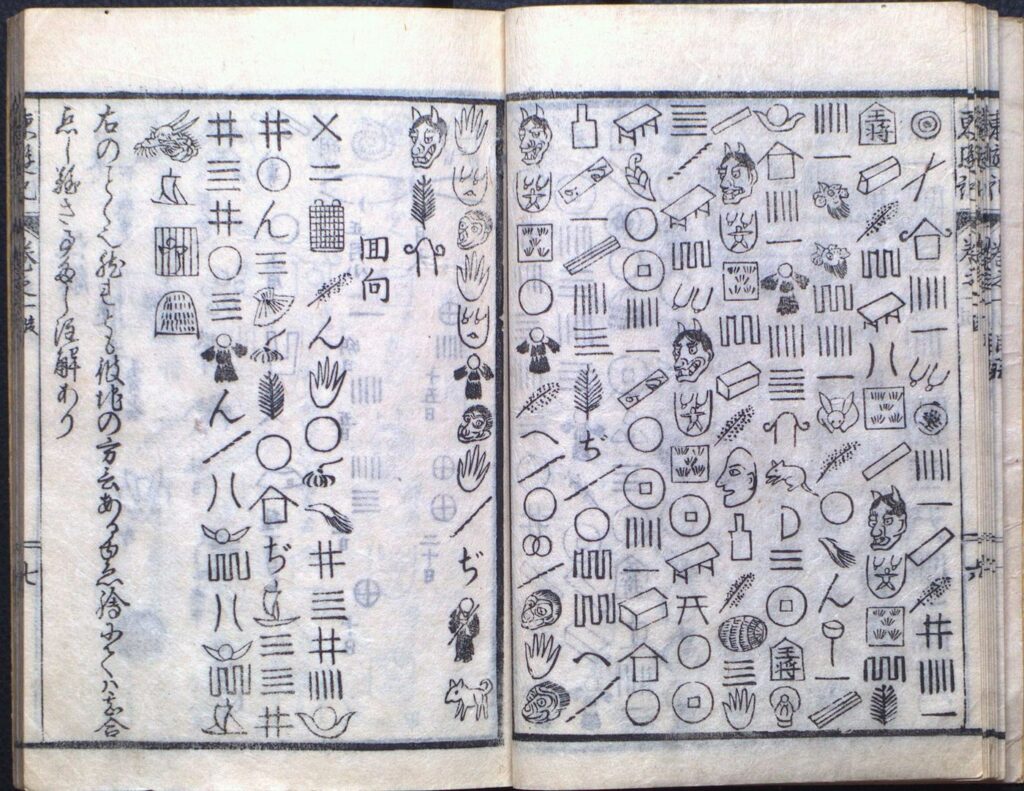

As for the illiterate — of whom, in complete contrast to modern-day Japan, there were many — what chance did they stand? Salvation, or at any rate a chance at salvation, arrived in the 17th century in the form of texts written just for them. “Japanese printers began creating a type of book for the illiterate, allowing them to recite sūtras and other devotional prayers, without knowledge of any written language,” writes Dukes. “The texts work by a rebus principle (known as hanjimono), where each drawn image, when named aloud, sounds out a Chinese syllable.” Geared toward an agricultural “readership,” this system drew its imagery from what they knew: farming tools, domestic animals, and even figures of myth.

The sections here come from a 20th-century example of this type of publication, variously Mekura-kyō or Monmō-kyō, held by the British Library. It contains a rendition of the text of the Heart Sūtra, the most widely known piece of scripture in the canon of Mahāyāna Buddhism, and as the Kyoto National Musem’s Eikei Akao puts it, “probably the best-known, most well-loved sutra in Japan.” (You may also remember the 37-minute version performed by beatboxing Buddhist monk Yogetsu Akasaka, which we previously featured here on Open Culture.) Not long ago, the United States Library of Congress posted this Heart Sūtra for the illiterate to its Facebook page. The occasion? World Emoji Day.

“Because these pictures represent sounds, rather than objects or ideas, they don’t really act as pictograms the way emoji do,” admits the writer of the Library of Congress’ post. “But in their icon-like appearance, succinct and functional, they do bear a resemblance to our use of emoji today.” It was then reblogged on Language Log, one of whose commenters offered some explanation of the system as seen in the pictures: “The Sanskrit phrase ‘Prajñāpāramitā’ is rendered ‘Hannyaharamita’ in Japanese. ‘Hannya’ here is written with a drawing of the hannya demon mask from Noh. ‘Harami’ appears to be a picture of a body (mi) in an abdomen (hara), and then ‘ta’ is a picture of a ricefield (tanbo, the “ta” of many Japanese names, like Tanaka and Toyota).” Hands have been wringing about the potential of internet communication to deliver us into a “post-literate” society; perhaps these curious chapters in the history of the Japanese language show us where to go from there.

Related contrast:

Breathtakingly Detailed Tibetan Book Printed 40 Years Before the Gutenberg Bible

The World’s Largest Collection of Tibetan Buddhist Literature Now Online

A Beatboxing Buddhist Monk Creates Music for Meditation

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities and culture. His projects include the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.

Languages and origins have always peaked my curiosity. This article is absolutely fascinating.