New York is never just one city; it’s always several, interacting with – or pushing out – each other. This goes for the city’s architecture as much as for its population. Its strata of public works projects, cultural institutions, department stores, hotels, hostels, housing, and skyscraping office buildings tell the story of its evolution. Now, artists, urbanists, and architects protest faceless condos and big box stores. In decades past, they fought the faceless towers that rose into the atmosphere and blocked the sun. Such opposition stretches back well over 100 years, to the turn-of-the-century New York of the Flatiron Building and Beaux Arts wonders like Penn Station, a building, The New York Times writes, that “once made travelers feel important.”

“In the 1890’s,” writes Christopher Gray, Paris-trained architect Ernest Flagg “denounced the growing crop of skyscrapers, and by the turn of the 20th century he was horrified by the darkened streets and raw side walls produced by such buildings.” Flagg’s opinions were of little interest to his New York employers, so he “shifted his focus to reforming skyscraper design” instead of decrying them outright.

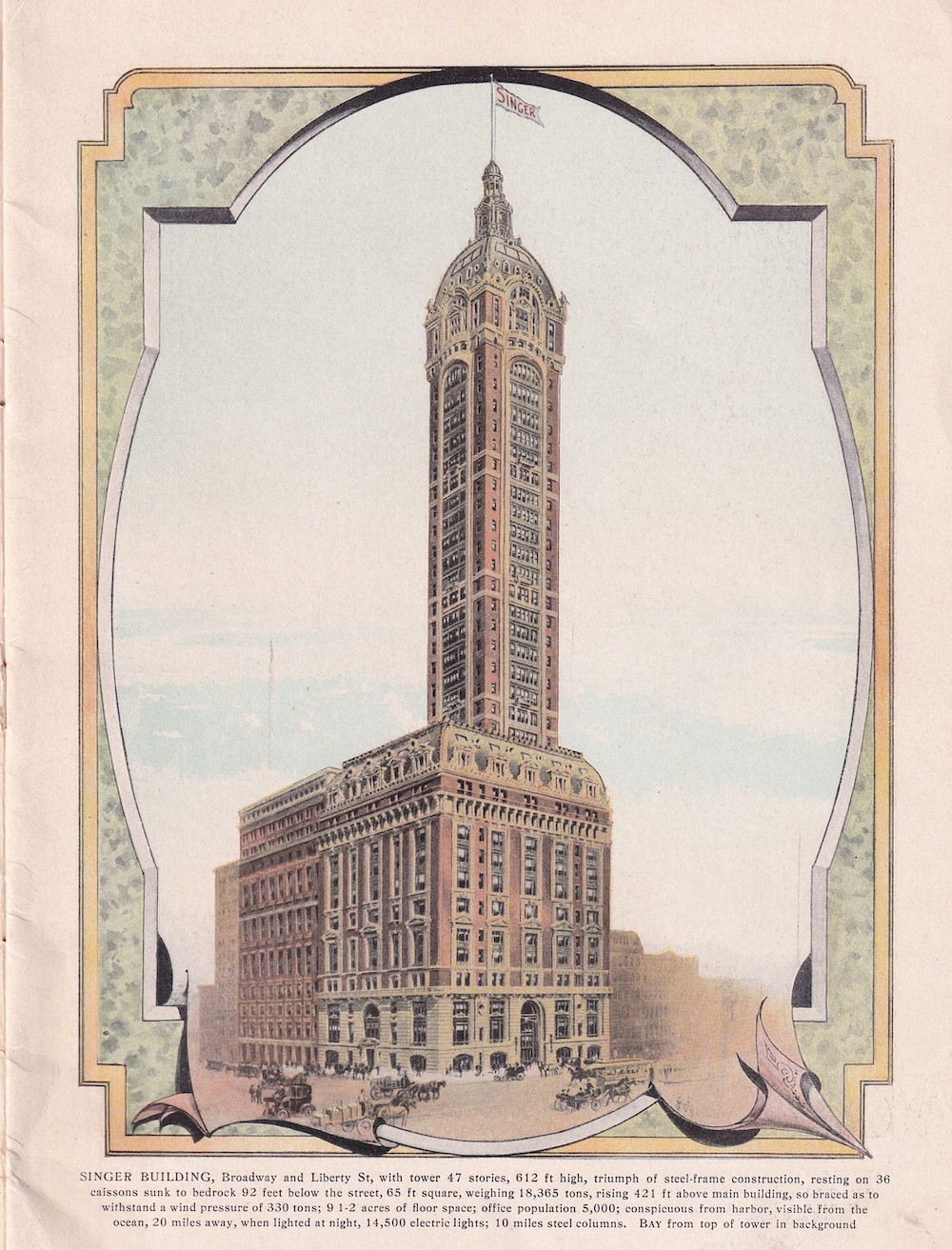

The endeavor produced a modern marvel, “a one-of-a-kind tower” rising above the New York City skyline, notes the video above, “a total masterpiece of architecture and engineering unlike anything seen before” — the Singer Tower, built for the Singer Sewing Machine Company in 1908.

So impressive was it for its time that Flagg’s building won comparisons to the pyramids of Ancient Egypt. For a brief moment, between the years 1908 and 1909, it was the tallest building in the world, until it lost the title to the Metropolitan Life Insurance Company Tower, another unusual building unlike the rectangular skyscrapers against which Flagg railed. Unconcerned with maximizing available real estate, he “urged that skyscraper towers more than 10 or 15 stories high should be set back from the property lines, so that the tower occupied only one-quarter of the lot,” writes Gray. “All four sides could then be treated architecturally, and ‘we should soon have a city of towers instead of a city of dismal ravines.’ ”

Working in a Beaux-Arts style, Flagg put his theories to the test in the Singer Tower, also called the Singer Building, expanding an original 10-story base to 14 stories, then building a smaller 33 ‑story tower atop it. Capped by a dome with a lantern and flagpole rising from it, the tower’s “bulbous top became one of New York’s best known landmarks.” Its lobby had the ornate luxury “seen in world’s fair and exposition architecture of the period.” But Flagg’s vision of “a city of free-standing towers” would remain the dream of a single architect. Despite his work for legislation to curb skyscrapers that took up entire city blocks, such buildings, including the 34-story City Investing Building, would continue to rise around the distinctive Singer Tower.

Finally, Flagg’s quirks proved too much for New York’s real estate elite. When the Singer company moved its headquarters in 1961, interest in the Tower remained low “because the small square footage of the building’s narrow tower was antithetical to the booming growth of modern business, which demanded more, not less, office space,” writes Katie Hiler. Deconstruction of the first skyscraper “ever to be peacefully demolished” began in 1967, five years after the demolition of Penn Station. In place of the Singer Tower would rise the 54-story One Liberty Plaza, a harbinger of things to come in the city’s new financial hub, the World Trade Center.

Related Content:

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

Leave a Reply