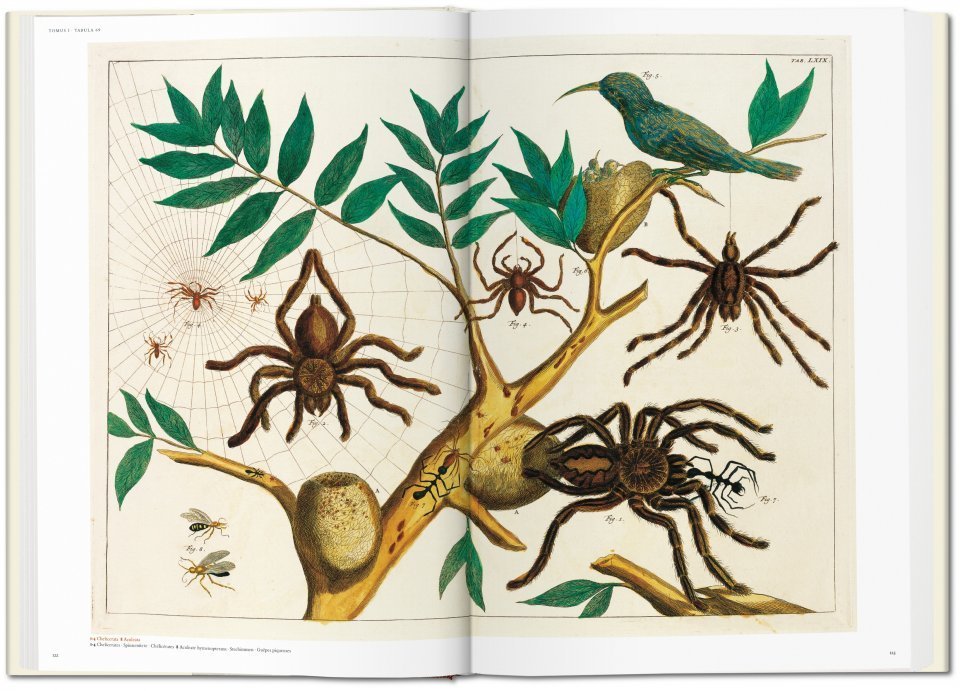

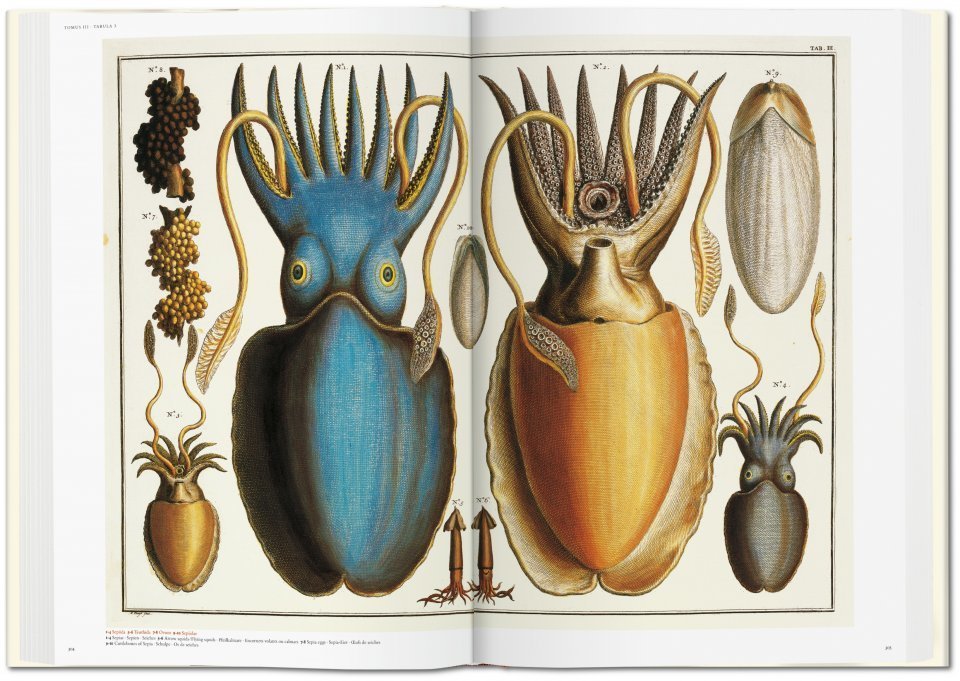

In the eighteenth century, a European could know the world in great detail without ever leaving his homeland. Or he could, at least, if he got into the right industry. So it was with Albertus Seba, a Dutch pharmacist who opened up shop in Amsterdam just as the eighteenth century began. Given the city’s prominence as a hub of international trade, which in those days was mostly conducted over water, Seba could acquire from the crew members of arriving ships all manner of plant and animal specimens from distant lands. In this manner he amassed a veritable private museum of the natural world.

The “cabinets of curiosities” Seba put together — as collectors of wonders did in those days — ranked among the largest on the continent. But when he died in 1736, his magnificent collection did not survive him. He’d already sold much of it twenty years earlier to Peter the Great, who used it as the basis for Russia’s first museum, the Kunstkammer in St. Petersburg.

What remained had to be auctioned off in order to fund one of Seba’s own projects: the Locupletissimi rerum naturalium thesauri accurata descriptio, or “Accurate description of the very rich thesaurus of the principal and rarest natural objects,” pages of which you can view at the Public Domain Review and the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

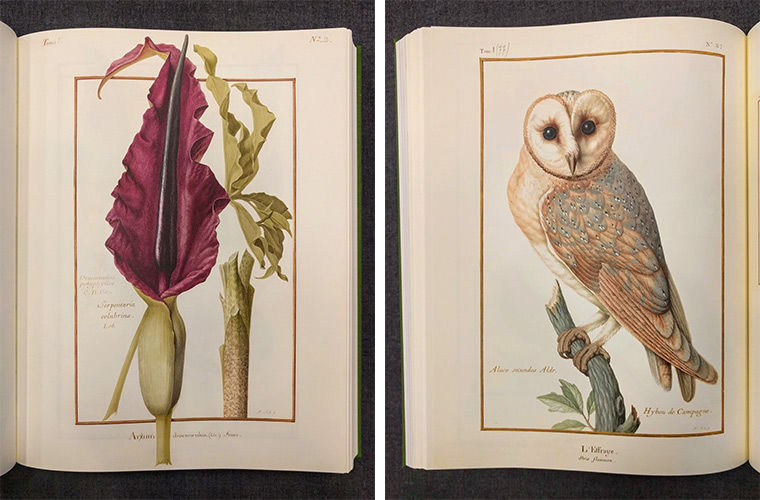

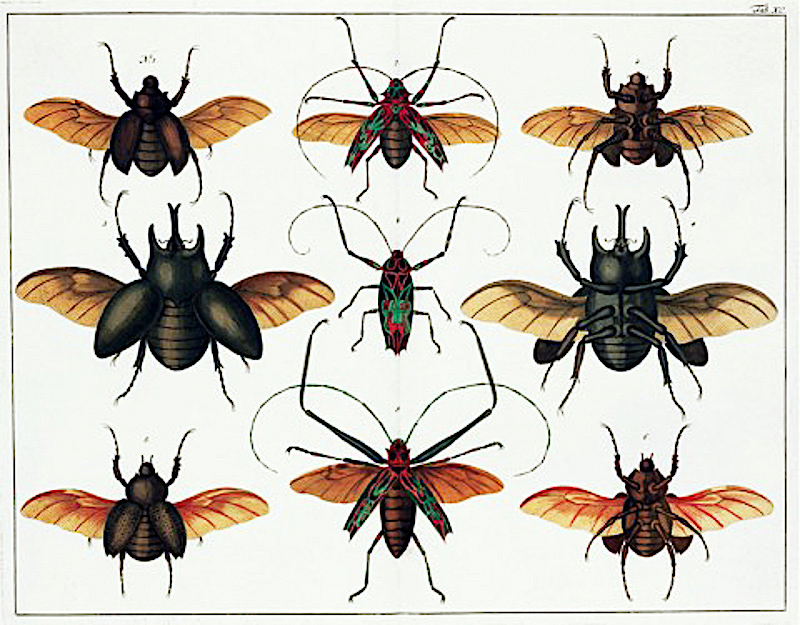

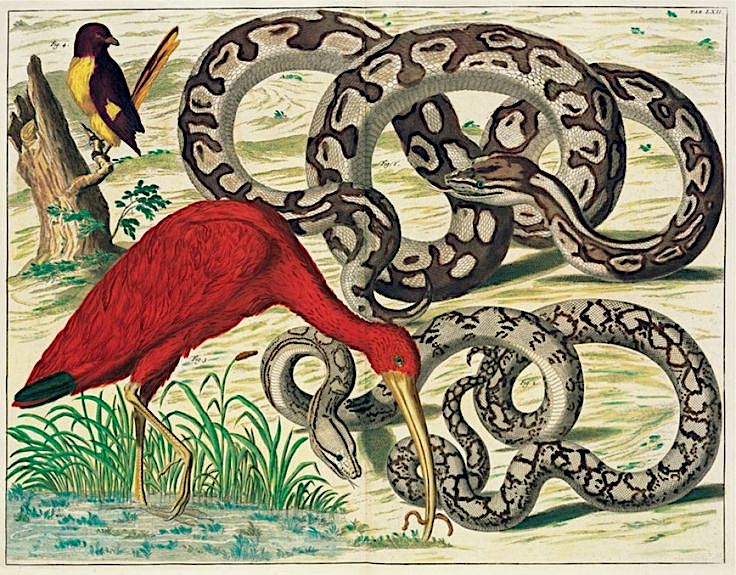

This four-volume set of books constituted an attempt to catalog the variety of living things on Earth, a formidable endeavor that Seba was nevertheless well-placed to undertake, rendering each one in engravings made lifelike by their depth of color and detail. The lavish production of the Thesaurus (more recently replicated in the condensed form of Taschen’s Cabinet of Natural Curiosities) presented a host of challenges both physical and economic. But there was also the intellectual problem of how, exactly, to organize all its textual and visual information. As originally published, it groups its specimens by physical similarities, in a manner vaguely similar to the much more influential system published by Swedish scientist Carl Linnaeus in 1735.

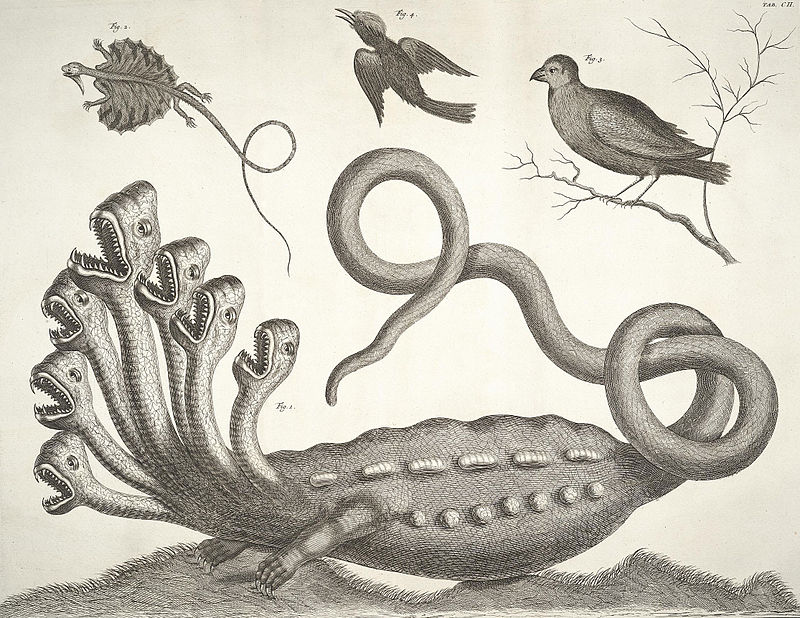

Linnaeus, as it happens, twice visited Seba to examine the latter’s famous collection. It surely had an influence on his thinking on how to name everything in the biological realm: not just the likes of trees, owls, snakes, and jellyfish, but also the “paraxoda,” creatures whose existence was suspected but not confirmed. These included not only the hydra and the phoenix, but also the rhinoceros and the pelican.

Eighteenth-century Europeans possessed much more information about the world than did their ancestors, but facts were still more than occasionally intermixed with fantasy. Given the strangeness of what had recently been documented, no one dared put limits on the strangeness of what hadn’t.

Note: A number of the vibrant images on this page come from the Taschen edition.

Related Content:

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities and culture. His projects include the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.

Leave a Reply