If you’ve ever wondered why one of science fiction’s greatest honors is called the “Hugo,” meet Hugo Gernsback, one of the genre’s most important figures, a man whose work has been variously described as “dreadful,” “tawdry,” “incompetent,” “graceless,” and “a sort of animated catalogue of gadgets.” But Gernsback isn’t remembered as a writer, but as an editor, publisher (of Amazing Stories magazine), and pioneer of science fact, for it was Gernsback who first introduced the earth-shaking technology of radio to the masses in the early 20th century.

“In 1905 (just a year after emigrating to the U.S. from Germany at the age of 20),” writes Matt Novak at Smithsonian, “Gernsback designed the first home radio set and the first mail-order radio business in the world.” He would later publish the first radio magazine, then, in 1913, a magazine that came to be called Science and Invention, a place where Gernsback could print catalogues of gadgets without the bother of having to please literary critics. In these pages he shone, predicting futuristic technologies extrapolated from the cutting edge. He was understandably enthusiastic about the future of radio. Like all self-appointed futurists, his predictions were a mix of the ridiculous and the prophetic.

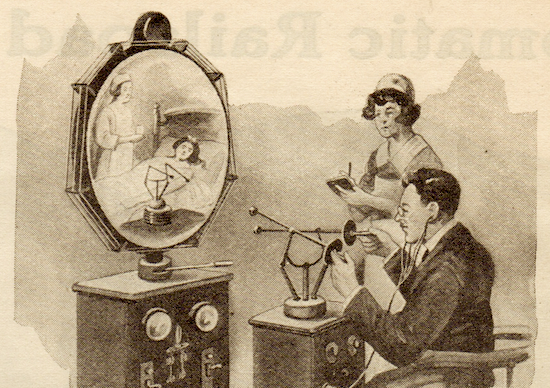

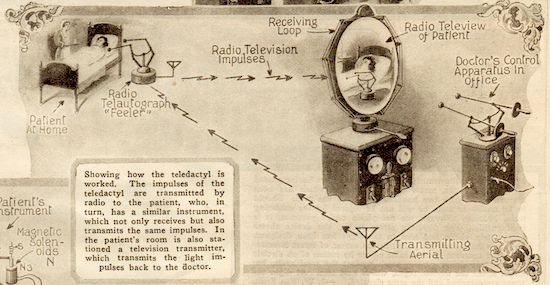

Case in point: Gernsback theorized in a 1925 Science and Invention article that communications technologies like radio would revolutionize medicine, in exactly the ways that they have in the 21st century, though not quite through the device Gernsback invented: the “teledactyl,” which is not a robotic dinosaur but a telemedicine platform that would allow doctors to examine, diagnose, and treat patients from a distance with robotic arms, a haptic feedback system, and “by means of a television screen.” Never mind that television didn’t exist in 1925. Sounding not a little like his contemporary Buckminster Fuller, Gernsback insisted that his device “can be built today with means available right now.”

It would require significant upgrades to radio technology before it could support the wireless internet that lets us meet with doctors on computer screens. Perhaps Gernsback wasn’t entirely wrong — technology may have allowed for some version of this in the early 20th century, if medicine had been inspired to move in a more sci-fi direction. But the focus of the medical community — after the devastation of the 1918 flu epidemic — had understandably turned toward disease cure and prevention, not distance diagnosis.

Gernsback looked fifty years ahead, to a time, he wrote, when “the busy doctor… will not be able to visit his patients as he does now. It takes too much time, and he can only, at best, see a limited number today.” Home visits did not last another fifty years, but remote medicine didn’t take their place until almost 100 years after Gernsback wrote. Indeed, the webcams that now give doctors access to patients in the pandemic only came about in 1991 for the purpose of making sure the break room in the computer science department at Cambridge had coffee.

Gernsback even anticipated advances in space medicine, which has spent the last several years building the technology he predicted in order to perform surgeries on sick and injured astronauts stuck months or years away from Earth. He would have particularly appreciated this usage, though he isn’t given credit for the idea. Gernsback also deserves credit for poking fun at himself, as he seemed to realize how hard it was for most people to take him seriously.

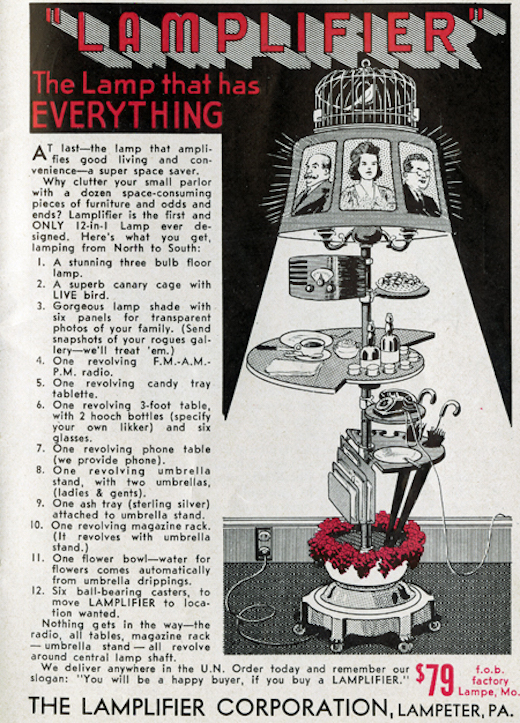

To non-visionaries, the technologies of the future would all seem equally ridiculous today, as in the pages of Gernsback’s satirical 1947 publication, Popular Neckanics Gagazine. Here, we find such objects as the Lamplifier, “the lamp that has EVERYTHING.” Gernsback’s love of gadgets blurred the boundaries between science fiction and fact, always with the strong suggestion that — no matter how useful or how ludicrous — if a machine could be imagined, it could be built and put to work.

Related Content:

A 1947 French Film Accurately Predicted Our 21st-Century Addiction to Smartphones

Sci-Fi Author J.G. Ballard Predicts the Rise of Social Media (1977)

Arthur C. Clarke Predicts in 2001 What the World Will Look By December 31, 2100

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

Also, Kurt Lasswitz, the father of German Sci-Fi, wrote a short story in 1899 called “die Fernschule”(“the Long Distance School”) which basically (and accurately — somewhat) predicts Zoom classes.