The stories of King Arthur and his court took shape over a period of a few hundred years; like most ancient legends, they evolved through many iterations — not a little like the stories in modern-day comic books. “The medieval Arthurian legends were a bit like the Marvel Universe,” explains Laura Campbell, a medieval language scholar at Durham University. “They constituted a coherent fictional world that had certain rules and a set of well-known characters who appeared and interacted with each other in multiple different stories.”

The first account of Arthur comes from a text in Latin called the Historia Brittonum, a compilation of sources assembled sometime in 829 or 830. Here, Arthur is mentioned as a historical figure, “variously described,” notes the British Library, “as a war lord (dux bellorum), as a Christian soldier who carries either an image of the virgin or Christ’s cross, and as a legendary figure associated with miraculous events.”

Merlin the magician — the figure we most associate with miraculous events in the Arthurian legends — doesn’t show up for another two hundred years or so, in Geoffrey of Monmouth’s History of the Kings of Britain. “After Geoffrey,” writes Kathryn Walton at Medievalists.net, “Merlin becomes a fixture of the Arthurian legend and appears in all kinds of different versions of the story across the Middle Ages.” One Merlin story that appears in many versions involves a figure called Nimue, Viviane, and other names in French, English, and Welsh. (She is sometimes identified with the Lady of the Lake).

The Merlin and Vivien stories have “survived throughout the ages in a way that not many other stories have,” the University of Rochester’s Robyn Pollack writes, “because writers have found remarkable ways to transform the characters and the narrative over the centuries.” Now, scholars at the University of Bristol have announced, two years after its discovery, the authentication of a fragment containing yet another version of the story.

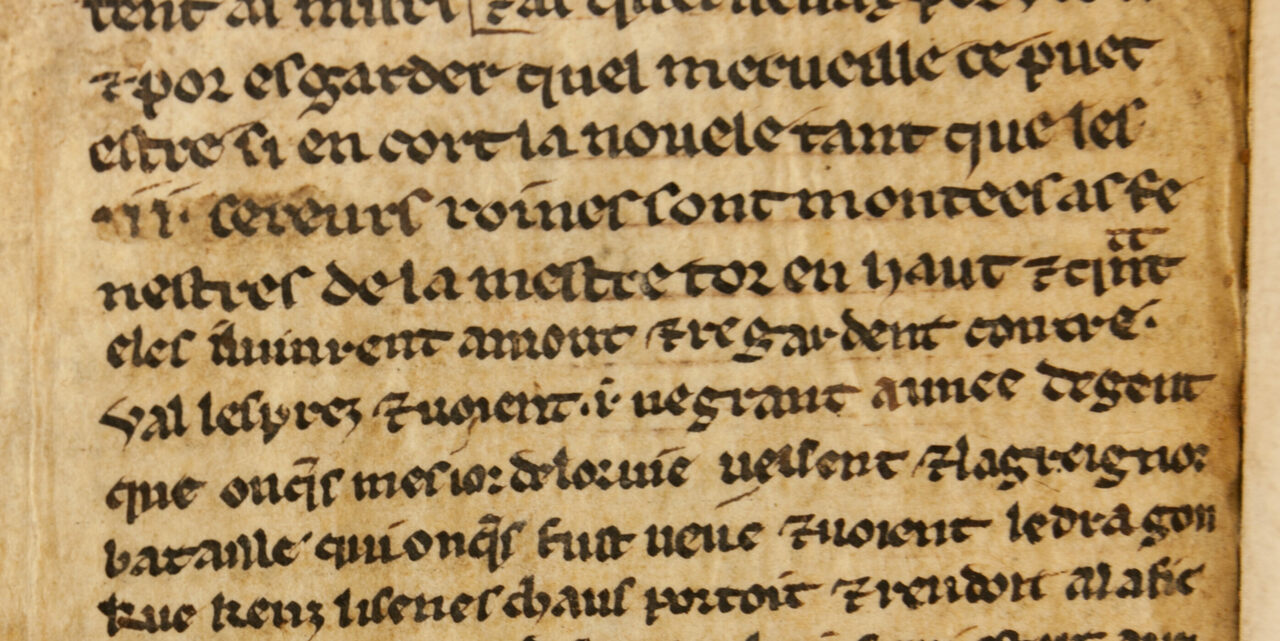

Found glued into the binding of a late 15th century book at the Bristol public library (one of the world’s oldest libraries), the seven fragments in Old French, dated between 1250 and 1275, contain the “most chaste version” of the Merlin and Viviane legend, says Leah Tether, co-author of the new English translation and commentary, The Bristol Merlin: Revealing the Secrets of a Medieval Fragment. “The most significant difference to be found in this particular set of fragments is where Viviane, the enchantress, casts a spell.”

In other versions, her magic inscribes three names on her groin, a spell that keeps Merlin away from the same area. In the re-discovered fragment, which shows evidence of two scribal hands, Viviane engraves the three names on a ring, thereby preventing Merlin from speaking to her. “With medieval texts there was no such thing as copyright,” says Campbell, one of the project’s translators and authors. “So, if you were a scribe copying a manuscript, there was nothing to stop you from just changing things a bit.”

Part of a collection of Arthurian stories known as the Vulgate Cycle, the fragment provides further evidence of the Merlin character’s evolution, and considerable softening, over time. At his first introduction, Merlin was the literal son of Satan, a kind of antichrist sent to earth to wreak havoc. Over the centuries, he became much less sinister, transforming into the wise advisor of the ideal English king, Arthur, a character who did a fair bit of transforming himself as his legend grew and changed.

via Atlas Obscura

Related Content:

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

Leave a Reply