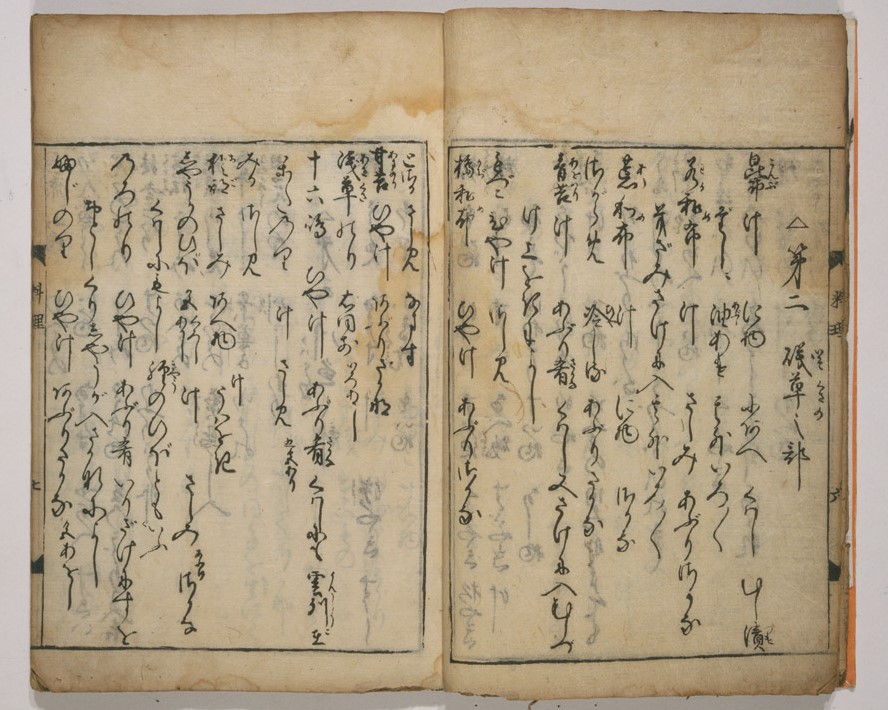

Maybe your interest in Japan was first stoked by the story of the seventeenth-century shōgun Tokugawa Ieyasu and his campaign to unify the country. Or maybe it was Japanese food. Either way, culinary and historical subjects have a way of intertwining in every land — not to mention making countless possible literary and cultural connections along the way. For the curious mind, enjoying a Japanese meal may well lead, sooner or later, to reading Japan’s oldest cookbook. Published in 1643, the surviving edition of Ryori Monogatari (variously translated as “Narrative of Actual Food Preparation” or, more simply, “A Tale of Food”) resides at the Tokyo National Museum, but you can read a facsimile at the Tokyo Metropolitan Library.

Translator Joshua L. Badgley did just that in order to produce an online English version of the venerable recipe collection. In an introductory essay, he describes his translation process and offers some historical context as well. Ryori Monogatari was written early in the era of the Tokugawa shogunate, which had been founded by the aforementioned Ieyasu.

“For the previous 120 years, the country had been engulfed in civil wars,” but this “Age of Warring States” also “saw the first major contact with Europeans through the Portuguese, who landed in 1542, and later saw the invasion of Korea.” The foreigners “brought with them new ideas, and access to a new world of food, which continues to this day in the form of things like tempura and kasutera (castella).”

Consolidated by Ieyasu, Japan’s subsequent 250-year-long peace “saw an increased emphasis on scholarship, and many books on the history of Japan were written in this time. In addition, travel journals were becoming popular, indicating various specialties and delicacies in each village.” The now-unknown author of Ryori Monogatari seems to have gone around collecting recipes that had been passed down orally for generations — hence the sometimes vague and approximate instructions. But unusually, note publishers Red Circle, the book also “includes recipes for game at a time when eating meat was viewed by most as a taboo.” In it one finds instructions for preparing venison, hare, boar, and even raccoon dog.

Your fascination with Japan might not have begun with a meal of raccoon dog. But Ryori Monogatari also includes recipes for sashimi, sushi, udon and yakitori, all eaten so widely around the world today that their names no longer merit italics. Taken together, the book’s explanations of its dishes open a window on how the Japanese ate during the Edo period, named for the capital city we now know as Tokyo, which lasted from 1603 to 1863. (In the video just above, Tasting History vlogger Max Miller makes a typical bowl of Edo noodles, based on a recipe from the 1643 cookbook.) “From the mid-Edo period,” says the Tokyo National Museum, “restaurants began to emerge across Japan, reflecting a new trend toward enjoying food as recreation.” By the late Edo period, an era captured by ukiyo‑e master Hiroshige, eating out had become a national pastime. And not so long thereafter, going for Japanese food would become a culinary, historical, and cultural treat savored the world over.

Related Content:

An Archive of 3,000 Vintage Cookbooks Lets You Travel Back Through Culinary Time

Cookpad, the Largest Recipe Site in Japan, Launches New Site in English

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities, the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.

Leave a Reply