Daisuke Inoue has been honored with a rare, indeed almost certainly unique combination of laurels. In 1999, Time magazine named him among the “Most Influential Asians of the Century.” Five years later he won an Ig Nobel Prize, which honors particularly strange and risible developments in science, technology, and culture. Inoue had come up with the device that made his name decades earlier, in the early 1970s, but its influence has proven enduring still today. It is he whom history now credits with the invention of the karaoke machine, the assisted-singing device that the Ig Nobel committee, awarding its Peace Prize, described as “an entirely new way for people to learn to tolerate each other.”

The achievement of an Ig Nobel recipient should be one that “makes people laugh, then think.” Over its half-century of existence, many have laughed at karaoke, especially as ostensibly practiced by the drunken salarymen of its homeland. But upon further consideration, few Japanese inventions have been as important.

Hence its prominent inclusion in Japanologist Matt Alt’s recent book Pure Invention: How Japan’s Pop Culture Conquered the World. As Alt tells its story, the karaoke machine emerged out of Sannomiya, Kobe’s red-light district, which might seem an unlikely birthplace — until you consider its “some four thousand drinking establishments crammed into a cluster of streets and alleys just a kilometer in radius.”

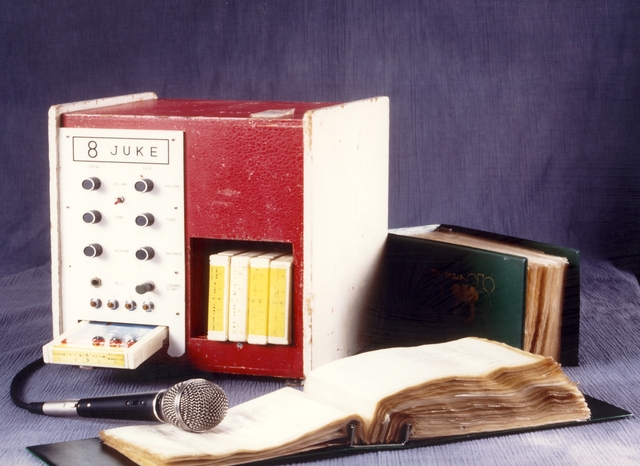

In these bars Inoue worked as a hiki-katari, a kind of freelance musician who specialized in “sing-alongs, retuning their performances on the fly to match the singing abilities and sobriety levels of paying customers.” This was karaoke (the Japanese term means, literally, “empty orchestra”) before karaoke as we know it. Inoue had mastered its rigors to such an extent that he became known as “Dr. Sing-along,” and the sheer demand for his services inspired him to create a kind of automatic replacement he could send to extra gigs. The 8 Juke, as he called it, amounted to an 8‑track car stereo connected to a microphone, reverb box, and coin slot. Pre-loaded with instrumental covers of bar-goers’ favorite songs, the 8 Jukes Inoue made soon started taking in more coins than they could handle.

“When I made the first Juke 8s, a brother-in-law suggested I take out a patent,” Inoue said in a 2013 interview. “But at the time, I didn’t think anything would come of it.” Having assembled his invention from off-the-shelf components, he didn’t think there was anything patentable about it, and unknown to him, at least one similar device had already been built elsewhere in Japan. But what Inoue invented, as Alt puts it, was “the total package of hardware and custom software that allowed karaoke to grow from a local fad into an enormous global business.” Had it been patented, says Inoue himself, “I don’t think karaoke would have grown like it did.” Would it have grown to have, as Alt puts it, “profound effects on the fantasy lives of Japanese and Westerners both”? And would Inoue have found himself onstage more than 30 years later at the Ig Nobels, leading a crowd of Americans in a round of “I’d Like to Teach the World to Sing”?

Related Content:

The 10 Commandments of Chindōgu, the Japanese Art of Creating Unusually Useless Inventions

This Man Flew to Japan to Sing ABBA’s “Mamma Mia” in a Big Cold River

Karaoke-Style, Stephen Colbert Sings and Struts to The Rolling Stones’ “Brown Sugar”

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities, the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.

Leave a Reply